In the first part of this interview, we spoke to German independent film-maker Lars Henriks about his “Cthulhu trilogy”, which mashed up eldritch horror with rom-com, family drama and punk band Scooby Doo-like investigations. Now, we move into the second half of his career, where things go in a different direction, with Lars no longer flying quite as solo!

As in the earlier installment, we’ll be intercutting the interview with our review of the films in question. But first, over to Lars, as we learn about the hell of funding movies in Germany, why dog owners suck, and life under COVID quarantine.

Your last few movies have been collaborations with Nisan Arikan. What brought you together, and how does it work in practice?

I’ve met Nisan when we were both 17 and starting drama school together. She got hired by a theatre company after a year and quit drama school to work as an actress then, never looking back, while I finished my diploma, so we kind of lost touch. When I was casting Zeckenkommando, I asked her if she wanted to play Xena, but she was in New York then. When she came back to Hamburg, half a year later, we hadn’t stopped talking about possible projects to do together. We hadn’t stopped talking in general.

Leon Must Die grew out of a discussion we had among the two of us, about whether or not it would be cool to be able to upload one’s mind into a computer or cloud of some sort. I wrote the script in three days after that conversation, after which Nisan and our DoP Christian gave a lot of feedback and we went over everything together until we were all happy with it.

I like to think of it as the cinematic equivalent of a punk band.

Not only have Nisan and I been a couple ever since production on “Leon”, we have also worked together on everything going forward. I write (often based on outlines co-developed with Nisan) and direct, Nisan edits and produces and sometimes acts. Christian Grundey is really the third person in this team, being the DoP on most films we’ve made since Leon. I like to think of it as the cinematic equivalent of a punk band. It was also Nisan’s idea to enter “Leon” into many international film festivals via FilmFreeway.

I had only ever tried to get recognised in Germany, which never worked. The German film industry works like this: You go to the federal funding board, where committees made up of representatives from political parties and some other institutions like the church decide what gets made and what doesn’t, and you ask for permission/money to make a movie. Based on their assessment of your movie’s adaptability to their guidelines (some bureaucratic, most political), they will say yes or no. Aesthetics or quality standards play no part here – the people in charge often proudly profess their ignorance towards film as an art form to demonstrate their impartiality.

If you do not get funding by them, this means you can not get into German film festivals as a German production. Most festivals ask specifically which funding board backed your film in the submission form. They will gladly take your submission fee but won’t look at your movie if you weren’t funded. This isn’t even malicious: They themselves receive federal funding, which they need to exist, and that comes tied to the funding board’s wishes to see their product represented – and only theirs. You can not get classic distribution in Germany, because distribution companies are also dependent on those funding boards. You can not get your film into cinemas yourself – because, you guessed it, those are dependent on the funding boards as well. In short: You can not get your movie seen in Germany if it is not backed by one of these boards, and forget about earning your production budget back.

If that were not so, there would be a populist German cinema that works without public funding. That kind of thing has ceased to exist since the current federal funding structure took shape in the late 60s / early 70s. Only since film production has become achievable without budgets, after the DSLR revolution around 2010, did it become possible to do anything remotely professional, without permission by the boards. But apart from our tiny Hamburg scene, I don’t see anyone doing it.

Sorry, got a little side-tracked there.

So, Nisan suggested trying to get seen elsewhere – And it worked remarkably well! “Leon Must Die” brought us to places like Vietnam, Derby, UK, and Sanford, Maine. I’ve never travelled sp much as when Leon was doing its festival tour. We won a bunch of awards, met some great people and just had so much fun in general! Not only that: after getting this seen more than anything else I had ever made, we also got in touch with IndieRights, a distribution company from Los Angeles that put Leon out on Prime Video and many other streaming services. That was an absolute novelty for me then and felt great.

Without Nisan, none of that would have happened. Ever since, we’ve started to concentrate more on getting our movies seen in other countries and less and less on Germany. Here, the situation is deliberately impossible for independent productions, newcomers and anything that looks like it might be “genre” (horror being the worst offender), and things have seriously gone up for us.

Leon muss sterben (2017)

Rating: B-

Dir: Lars Henriks

Star: Philip Spreen, Nisan Arikan, Viktoria Steiber, Alexander F. Obe

a.k.a. Leon Must Die

This is exactly what you would expect, if someone was to remake Terminator on a budget of… [checks IMDb] one hundred Euros. Yeah, this may be the second-cheapest feature film I’ve seen, ahead only of Who Killed Captain Alex?, which Wikipedia says cost $85. This is nowhere near so deranged or ambitious: the guiding ethos here is clearly “talk is cheap,” and when you see the action… let’s just say, you’ll understand why it’s so chatty. Yet it’s also quite charming: arguably it has more heart than Cameron’s classic. Imagine if the Terminator had fallen in love with Sarah Conner and refused to carry out its mission. That’s kinda what we have here.

“Sarah” is Leon (Spreen), a largely unsocial guy, who spends his time feeding ducks and drinking beer in the local park, or tinkering with technology. It’s the latter which is the problem. For his tech will eventually become a very, very dystopian future where everyone is compelled to live their lives out in a digitized form. From that time, Aqua (Arikan) is sent back to kill Leon and prevent him from completing his work. However, the more she finds out about him, the more inclined she is to believe she can talk him out of the project. Her boss in the future (Steiber) is less convinced, and sends the XB10-3 (Obe) back to kill Leon instead. Which is all rather awkward, since the XB10-3 also happens to be Aqua’s ex-boyfriend, prompting her to tell him, “I can’t be with a depressed robot anymore.”

As with most of Henriks’s other films, it’s the humanity at its heart that makes it work. There’s more than a little Hans Wagner about Leon – pointedly, at one point he’s watching that movie on television – with them both being introverts who unexpectedly find themselves at the centre of world-shattering events. He’s remarkably unfazed by the prospect of his death at the hands of Aqua, albeit with a very good reason. That’s revealed midway through, opening a whole barrel of philosophical and existential questions about life, death and the implications of alternatives. The film never comes up with answers: that likely isn’t the point though. Even if the discussions sometimes sound like something you’d hear down the Students Union on cheap beer night, there’s an honesty to them, reflecting the struggle we all have with these weighty topics.

As with most of Henriks’s other films, it’s the humanity at its heart that makes it work. There’s more than a little Hans Wagner about Leon – pointedly, at one point he’s watching that movie on television – with them both being introverts who unexpectedly find themselves at the centre of world-shattering events. He’s remarkably unfazed by the prospect of his death at the hands of Aqua, albeit with a very good reason. That’s revealed midway through, opening a whole barrel of philosophical and existential questions about life, death and the implications of alternatives. The film never comes up with answers: that likely isn’t the point though. Even if the discussions sometimes sound like something you’d hear down the Students Union on cheap beer night, there’s an honesty to them, reflecting the struggle we all have with these weighty topics.

Technically, it’s largely kept simple. Though there is one glorious moment where Leon and Aqua go to get some fried noodles. Rather than cutting to the pair eating the noodles, or following them into the shop, the camera waits outside, just absorbing Hamburg street life for a couple of minutes. This, or Leon eating his breakfast in what feels like real time, are good indications of the (lack of) pace you should expect here. Things happen when they need to, and much like life, you’re not going to get to your final destination any quicker by hurrying.

Performaniax and Bearkittens had a larger cast, and were made with a drama school in Hamburg. How did that come about?

After making four feature films (actually, there were seven, but three of them are conveniently lost) that nobody but me wanted to see made, on my own dime, without any kind of outside support, I felt things had to change. I wanted to stop working shitty acting jobs to pay the bills (touring all winter through school gymnasiums with a fairytale theatre troupe to pay for a tiny room in a shared flat with my dealer was a personal low point) and start getting paid to make movies.

“Leon Must Die” had gotten lots of eyeballs, but having movies up on streaming services doesn’t actually amount to much, in terms of money. I needed someone to pay for the productions up front. I approached my old drama school to sell them a novel concept for an image film: I was offering to make a web-series, 10 episodes of 10 minutes each, about a fictional group of acting students and their everyday adventures, casting their students. They bought it (for a ridiculously low amount of money) and we spent ten days shooting improvised comedic scenes with a cast of ten actors. It turned out nicely and they ordered a second season, which we made more colourful and sitcom-like, on a theatre ship, during winter.

I then became an acting teacher there. Naturally, I got bored with that. My remedy for that particular predicament was to offer my students, the graduating class, to develop and produce a feature around them, according to their specifications, showcasing their talents, which we would get into festivals and on big streaming services, if they helped crowdfund it. They enthusiastically agreed. Save for one of them, they did not help with the crowdfunding. Nisan did that mostly on her own. We got 5000€, which went directly into the movie (so, again, nothing for us).

I wanted to stop working shitty acting jobs to pay the bills and start getting paid to make movies.

Making “Bearkittens” was a ton of fun and we were very happy with the result. Of course, we had to moderate our tastes to fit a group of German acting students, so any horror element in our 2000’s teen horror inspired comedy is subdued to the point of nonexistence, but I like the tone, the jokes, the atmosphere and the weird characters.

Looking at it now I wish I would have had the freedom to make it a slasher film, but the way it is, it has this weird structure (taken from Bergman’s “Cries and Whispers”) and a kind of melancholia that I find very satisfying.

I am also really proud of the cast, who won a “Best Acting Ensemble” award at the Sanford Independent Film Festival that year. The school was happy with Bearkittens and agreed to put up the 5000€ for a second such production themselves. This time, I really wanted to make a horror film and mostly succeeded in convincing the students that it was a good idea to do so. Of course, in the end, it became a comedy, but that’s on me. I can’t resist making a joke when I see the opportunity…

Performaniax is perhaps your closest to a “pure” horror film. Was that, and the apparent giallo influence, deliberate from the beginning, or did it just turn out that way

It was very deliberate. Leading up to us starting to develop the film with the students (we do extensive rounds of improv to come up with characters before putting those characters into shared scenes and building a story around that), we made them watch a list of, I think, ten horror films we wanted them to know and of course “Suspiria” was on there. That was a really fun process.

Having colourful lighting in every scene became a dogma of mine on that film, to the chagrin of our camera crew. We brainstormed for every scene, going “What colour reflects this feeling or that feeling” when deciding on the colour for a scene, rather than taking any kind of physical logic into account. The aspect that more or less just turned out that way was the comedic tone. I mean, if you develop the basic shape of a movie in improv games with young actors, of course the results will often be comedic.

You know what? I quickly have to tell this story: The students in “Performaniax” were staunchly against any kind of supernatural elements, which quashed my original idea for the plot. I had originally wanted to tell a story about a failing theatre troupe, with a director with a habit of ordering fictional books from the library for a joke: the Necronomicon, Von unaussprechlichen Kulten, etc. One day, they order “The King in Yellow” – the fictional play that makes its readers go crazy, from Robert W. Chambers’ short story collection of the same name – and actually gets it. Then, the troupe starts staging said play and the ancient evil residing within slowly begins to twist reality.

They hated that pitch, so we didn’t do it.

Right now though, I am directing a stage adaptation of “Shakespeare and the King in Yellow”, an unproduced script by LA-based screenwriter Ryan Fitzgerald, that I have translated and adapted for the stage myself. It’s about the man who wrote “The King in Yellow” and his encounter with Shakespeare – it’s a lot of fun! One of the actresses, doing her research, wanted to know more about “The King in Yellow” and, cluelessly, ordered it. She didn’t get the short story collection, but the actual play! Now, obviously the play is fan fiction, but I still found this situation of life imitating unmade art pretty funny.

Bearkittens was mostly shot in a forest. What challenges did that pose?

Lack of toilets, dependence on weather, airplanes. Those were daily constants. Then, like in all public places: People.

We shot a scene in which three of the girls pick up trash by a meadow and midway through, three old ladies arrived with their dogs, sat down right beside us, talking loudly and making filming impossible. We asked them politely if it would be possible to maybe wait for ten minutes, let us finish shooting and sit down on another bench, ten meters away, for that time. They became very angry and agitated and kept yelling “This is a dog meadow, not a movie meadow!” Every time we tried to do a take. We had to stop, go to another place and start the scene over.

Dog owners are the worst, in general. I love dogs, but I have grown to haaaaate their people. Once, we were filming on a beach for another project. I was acting in that one. During a take, a dog ran up to me and bit me. Fucking bit me. Its owner stood a couple of meters away, weakly yelling: “Kennedy! Please, why do you do that? I told you not to. Kennedy. Please stop.” Kennedy didn’t stop and I had to get stitches.

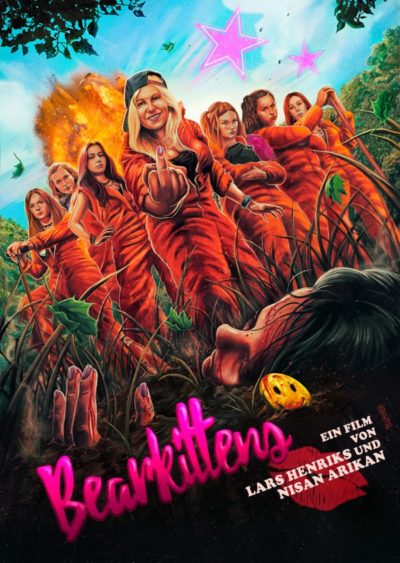

Bearkittens (2018)

Rating: C+

Dir: Lars Henriks

Star: Stefanie Borbe, Hannah Bortz, Lisa Eschenbrenner, Maren Kraus

Social worked Petra Keller (Borbe) is charged with taking a group of young female delinquents on a camping trip into the forest, part of the community service they’ve been ordered to carry out, as punishment for their various crimes. Needless to say, the trip doesn’t go as planned – does it ever? More or less none of the girls want to be there: few of them have any time for each other, though one of the few things they can agree on is that Petra is a complete waste of space. Which is why two of them decide to drug her with sleeping pills found in another participant’s bag, in order to get their supervisor out of the way, so they can have some real fun. That doesn’t go as planned either.

This is a particularly lightly-plotted exercise. In terms of things actually happening, you don’t get much for the first hour. We are introduced to the players, cutting back and forth between their bickering and exploits in the forest, and short flashbacks to their lives outside the woods. Despite the lack of plot progression, it’s still decently watchable, with some of the scenes flat-out brilliant. My personal favourite was the deadpan monologue by Petra’s supervisor about her fat niece’s aspirations to be a ballet dancer – “Merle, in a tutu, you look like a snowball” – and their tragic result. As dark humour, it should be right up there with Phoebe Cates’s speech in Gremlins about why she hates Christmas.

Just do not expect to empathize with many of the characters, if any at all. The smart ones are utter bitches, and the nice ones are idiots; in this area, it’s a bit of a contrast to Henriks’s other works, where you tended to find something to appreciate in just about everyone. The film might have benefited from having someone who can provide a moral core, a heroine to whom the audience can relate. It’s something inspirations for this such as Heathers and Mean Girls certainly had. Indeed, there may simply be too many characters, especially given a running time of under 75 minutes, including credits. Though it is laudable to see a film with only one significant male part, which doesn’t feel the need to make a fuss about it.

Just do not expect to empathize with many of the characters, if any at all. The smart ones are utter bitches, and the nice ones are idiots; in this area, it’s a bit of a contrast to Henriks’s other works, where you tended to find something to appreciate in just about everyone. The film might have benefited from having someone who can provide a moral core, a heroine to whom the audience can relate. It’s something inspirations for this such as Heathers and Mean Girls certainly had. Indeed, there may simply be too many characters, especially given a running time of under 75 minutes, including credits. Though it is laudable to see a film with only one significant male part, which doesn’t feel the need to make a fuss about it.

The poster on the right hints at where this eventually ends up, albeit as mentioned above, not until we are deep into the second half (despite some hints about the woods being cursed). It is a typically Henriksian shift in tone, with the social comedy being replaced by something with a considerably darker attitude. However, what follows feels hurried at best, with some loose ends e.g. someone takes a shovel to the back of the head, and it’s never clear what happens to them thereafter. In terms of pure story, it’s the most interesting section, and I would have preferred to have seen it given more room to breathe.

Leon Must Die saw a shift into SF, with an obvious Terminator influence. What inspired this?

On one hand, there’s that conversation with Nisan. On the other hand, there’s a short on YouTube called “Eagles are turning people into horses”. I loved that handmade LoFi SciFi style and wanted to do something similar. There also was an article about the untapped potential of SciFi romance which I found really inspiring. Back then, I wanted to try to do every genre with no budget. I had a bunch of fantasy concepts ready to go, also. But at some point, “making movies with and for no money” seemed less and less like a fun challenge and more like a dumb life decision.

For someone who hasn’t read Ovid, what themes from Metamorphoses became part of Covid Metamorphoses

We were this really small group of people knowing each other really well for the most part, making a movie in our flat in December, while the whole world was on lockdown.

That’s a project that changed shape a lot. I originally came up with the idea for it to be another project for that same drama school. The idea was: In one apartment block, there are many flats. It’s during lockdown. In every flat, we see a myth from Ovid’s Metamorphoses play out, transferred to the modern day, with a few elements of magical realism. But the school hesitated to the point of breaking promises we had depended on financially, which made working with them ever again impossible. So, we offered our concept of building a movie around newcomer actors as a workshop ourselves, without the backing of a drama school. Restrictions got more strict every day and in the end we were only able to take three students.

This changed the concept. Now, we’re in just one flat all the time, seeing elements of the stories of characters like Medea, Orpheus, Narciss and Hermes collide, as well as many elements of other stories from Ovid’s work in details and references. Those who have read it can have a real field day with the movie, picking out all the small allusions, but that’s not necessary to understanding it at all. We also recreated a number of classical paintings inspired by the stories.

The “Metamorphoses” are, largely, about mythological characters becoming something they were not in the first place. They are going through changes. Often times, they will end up as trees, flowers, cows or constellations, but there is a personal growth aspect to the whole theme as well. That’s obviously what happens to our two main characters, also in ways very directly taken from the ancient work. I think many people feel like personal change has happened in a compressed way during the past couple of Covid years. So, to me, that really fits.

One of the three students was so unreliable during rehearsals that we threw him out, another one had another work commitment during the time of production last minute and had to exit as well, so we cast two actors we knew to play their parts. In the end, we were this really small group of people knowing each other really well for the most part, making a movie in our flat in December, while the whole world was on lockdown. It was kinda nice.

How was life in Hamburg during lockdown?

Quiet. We had a curfew after eight PM, meeting more than one friend at a time was forbidden, culture was shut down entirely, going to the supermarket was the most exciting thing to do in a day. It would have been boring, hadn’t it also been so incredibly desperate, since we were forbidden to work but still had to pay rent. I am very happy we didn’t live in a shared flat then.

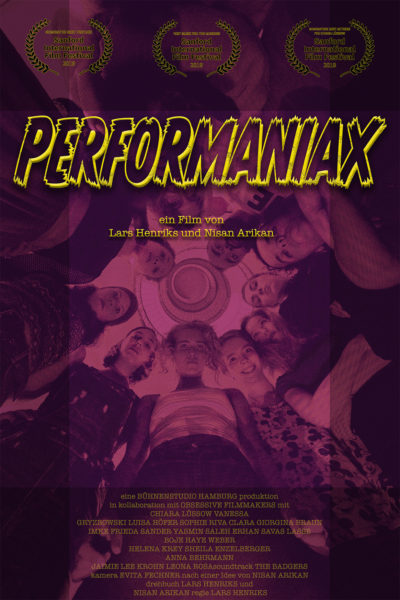

Performaniax (2019)

Rating: C+

Dir: Lars Henriks

Star: Chiara Lüssow, Vanessa Grzybowski, Luisa Höfer, Yasmin Saleh

Emily Ahrens (Lüssow) is an aspiring, and if the truth be told, not particularly good actress. She struggles even to get through auditions, until one day she gets an offer that seems too good to be true. 70,000 Euros for three weeks’ work – two weeks of rehearsals and one of shows – as part of the Performaniax theatre troupe. They are an avant-garde group, whose piece consists of a series of interactive “stations” designed to take the audience out of their comfort zone, by confronting them with taboo subjects like drugs, racism and homophobia. The show is overseen by a mysterious, almost absent director, and clearly very well funded from an equally cryptic source. The performers are as odd as you’d expect, some adopting a creepily method approach to their topics. “Kunst darf alles!” is their oft-repeated creed, which translates (per Google) as “Art can do anything!” The deeper we get, the more that phrase seems like a threat than a promise.

I “enjoyed” my share of performance art theatre in London during the nineties. Have to say, I found what we see of the Performaniax performance rather weak sauce. I certainly wasn’t offended, or even particularly challenged, especially with the distancing resulting from the format. [The audience reaction is occasionally amusing] Rather more interest comes from the shifting backstage dynamics. Emily rises from being a naive rookie, taking over the most illustrious station (the one dealing with sex), to the clear disgruntlement of the existing player. It’s a backstabbing environment, made worse by the vicious “notes” submitted from the director after the troupe’s performance on their opening night. In the final reel, the film changes tack dramatically, as Emily’s friend and agent gets some disturbing information about the Performaniax’s history, and tries to get her client out of there. When combined with Henriks’s fondness for colour filters, the movie suddenly feels like a version of Suspiria, with theatre replacing ballet.

I “enjoyed” my share of performance art theatre in London during the nineties. Have to say, I found what we see of the Performaniax performance rather weak sauce. I certainly wasn’t offended, or even particularly challenged, especially with the distancing resulting from the format. [The audience reaction is occasionally amusing] Rather more interest comes from the shifting backstage dynamics. Emily rises from being a naive rookie, taking over the most illustrious station (the one dealing with sex), to the clear disgruntlement of the existing player. It’s a backstabbing environment, made worse by the vicious “notes” submitted from the director after the troupe’s performance on their opening night. In the final reel, the film changes tack dramatically, as Emily’s friend and agent gets some disturbing information about the Performaniax’s history, and tries to get her client out of there. When combined with Henriks’s fondness for colour filters, the movie suddenly feels like a version of Suspiria, with theatre replacing ballet.

I do wish this aspect had shown up earlier, since it feels rushed, going from zero to resolution in 15 minutes. However, this is at least somewhat in line with Henriks’s other works: a late shift in tone appears almost a trademark. The performances are a mixed bag. It’s difficult to play an actor, because it adds a layer of meta-portrayal. I think Lüssow nails it well, especially in terms of her character’s development. Emily “grows” into a self-assurance that was nowhere to be seen in her opening audition. She finds herself in a way that, from some perspectives, may not exactly be a good thing. The rest of the cast aren’t as effective, in part because the parts they play seem largely defined by a single characteristic, offering less room for interpretation or modification. Hanna (Saleh), the show’s director, comes over best, perhaps because she is seen least. I sense familiarity with the German theatre scene may be of some help with nuances of the content. Yet likely no more so than you need a love of ballet to appreciate Black Swan.

F60 Kamikaze seems to have been an ongoing project for a few years. What can you tell us about it?

F60 Kamikaze breaks my heart every day. We went all out for that project and got punished severely. We are still working on it and I guarantee it will be finished and released this year, but the journey was and is a horror show.

F60 Kamikaze is an 8-part mini-series in the vein of “Skins” and “The End of the Fucking World”. It is set in the small town I myself grew up in and peopled with characters I actually knew (or caricatures thereof), though not autobiographical. It is very close to my heart. The night before Nisan and I moved to Spain for a year (2018, I think), we were emptying our Hamburg flat, talking about how to proceed. Nisan said: “Why not make one thing that doesn’t feel like no budget? One thing we don’t need to make excuses for? One perfect thing? Why not write one thing we can pull off perfectly, ourselves?” So, I did that. A teen dramedy series. The best thing I’ve ever written.

Good things happened early on: The biggest Hamburg based production house, with close ties to public TV, told us they were selling packages of content to Netflix regularly, without anyone ever really checking what’s in them. That way, they had managed to get an independently produced German series on there and promised to do the same for us. They even specified how much money we could count on. We were SO happy and believed them without any actual, official confirmation. Then, my favourite music label growing up, Hamburg-based Audiolith Records, came on board, letting us use their music (the soundtrack of my youth) and even having one of their trendiest acts play a concert in the series. I was living the dream!

We went deep into debt to be able to produce the series. Over the span of two years, with a dream cast and a great crew, we shot the whole thing. Most of that time, Nisan and I were actually starving (getting by on mouldy bread from food sharing places) to make the production possible (credit was used up early on). But it was worth it. We shot some incredible stuff. I couldn’t be prouder of what we’ve achieved. Then came the shock: Of course said production house didn’t deliver on their promise. Didn’t deliver on anything, actually.Their Netflix dealings had become more regulated and other than that, they really didn’t have anything to offer. So, there we were, stranded with this big series, out of money, without even any possibility to do the post-production because we had shot files so big, our laptop couldn’t handle them.

From then on, we went looking for help. A veritable parade of shady producers came in, promised us the world, couldn’t deliver and disappeared again. The level of frustration is hard to put in words. Just to give you a hint of the hell it has been, one of the hundreds of such stories we’ve lived through: There’s a big festival for series in Germany, the biggest one of its kind over here. It’s organised by many big production houses and funding boards. We got into their 2020 edition. It was online (due to lockdown). They built a website that looked like Netflix, but instead of a finished series, you’d get a pitch video. Since we were already done shooting, our pitch was the most polished by far and made the best numbers, too.

We shot some incredible stuff. I couldn’t be prouder of what we’ve achieved. Then came the shock…

I got exactly one meeting out of that – with a different department of that Hamburg based studio that had let us down so badly. The guy I talked to told me how impressed he was with our pitch and that he’d be in touch. He wouldn’t. A couple of weeks later though, that production house had a joint invitation of tenders, together with the Hamburg funding board. They were asking for concepts for a series just like ours – using my exact words from the pitch for our series to describe what they were looking for. I was infuriated, but we need to eat, so we put together a team and a concept pitch. Since they wanted something exactly like what we had just done, we figured they might like other ideas of ours, too, and submitted it. They didn’t even look at it: I don’t know if those committees don’t know filmmakers can see if their submitted videos are watched or not, or if they just don’t give a fuck.

We ran into pretty solid and downright sadistic walls all around. We finally went even deeper into debt to buy a computer we could edit on. We put together our own editing facility and Nisan edited the whole thing, doing a lot of fine tuning over months, between film shoots. When she was finished, I composed and recorded the soundtrack. It’s all put together and we’re SO proud of it. Now, the sound mixing needs to be done, as well as the color grading. We both can’t do grading, and the sound mix is a bit too complex for my modest skills this time, so, again, we’re dependent on other people to help us out. We’ve been waiting for the project to make progress for a year. It will be done this year. I can’t bare it being still unfinished anymore. It’s our very best work, an uncompromised vision, and I want people to see it.

After getting it done, of course, there’s the matter of getting distribution, still… This horrible story just won’t end.

What are the biggest lessons you have learned over your career so far?

- You need collaborators who understand your vision, know their trade and can bring value to your films. People you like working with and without whom your movies would be worse. People you can communicate with properly and quickly on set, because you never have a lot of time on set to answer a never-ending string of complicated questions and solve a wide variety of problems.

- People who talk a great deal in filmmaking usually can’t deliver on their promises. The greatest professionals (and even, when it comes to casting, the most seasoned or well known actors) are usually pretty humble and practical minded.

- Anyone who says the word “professional” a lot is usually an amateur looking for excuses not to make a movie. “Yes, but let’s do it professionally” is a way to set up insurmountable hurdles for even getting started, used by people who are terrified of being found out as frauds.

- It can be detrimental to a project to always use the newest and most elaborate tech available when recording, since the resulting files can pose unnecessary challenges in post-production.

- Style is more important than resolution.

- Avant-garde films are a lot more pleasurable to make than anything that is supposed to feel mainstream.

- Long dialogue scenes are more challenging to shoot than you might think when putting together your schedule.

- It’s advisable to always work with the smallest cast, crew and setup the story will allow for. Don’t clutter your set with unnecessary people, your script with unnecessary characters or your studio with unnecessary gear.

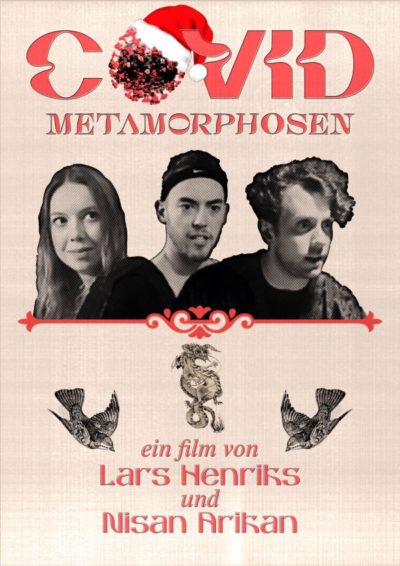

Covid Metamorphosen (2021)

Rating: B-

Dir: Lars Henriks

Star: Simon Burghart, Virginia Roncalli, Vincent Ellmers

Per the director, “If you can tell me what genre it belongs in, I’ll be grateful.” Nope. Sorry. I’ve got nothing. It’s kinda a one location drama, taking place almost entirely in a single Hamburg apartment while the city was on lockdown, over the festive season. But it’s somewhat of a fantasy as well, and often darkly amusing. Again, per Henriks, it contains characters and motifs from Ovid’s Metamorphoses. Which I have not read, though according to Wikipedia, “scholars have found it difficult to place the Metamorphoses in a genre.” So there’s that in common with the movie. I can say, my ignorance didn’t really seem to matter: the film stands well enough on its own, though perhaps familiarity with Ovid could add extra depth.

The apartment is owned by Tom (Ellmers), a cop with a sideline in dealing weed. His flatmate is Vivienne (Roncalli), who has long held a candle for Tom, to which he is totally oblivious, since he hasn’t got over his ex-girlfriend Sophie. One morning, there’s a knock on the door. It’s the highly eccentric Peter (Burghart), who wants to buy some drugs from Tom. Specifically, four drugs. He asks Tom to roll him a joint, and before you know it, pizza has been consumed, beers drunk and the sudden announcement of the lockdown results in Peter becoming a new flatmate. As the days turn into months, the unlikely trio stagnate in their residence, yet with a little prodding from Peter, both Tom and Vivienne come to realize certain truths, which perhaps offer them a path forward.

Peter is the most apparently mythological character, whom we first meet standing on top of a burned-out car, proclaiming lines like, “My soul is wrought to sing of forms transformed to bodies new and strange! Immortal gods inspire my heart, for ye have changed yourselves.” Where does he come from? Where does he go? He feels like a messenger of the Greek gods – or perhaps even a god himself, bored with life in Olympus. For a while, I thought it was Henriks himself playing the character. There’s a naivety present, yet you sense this is a cover for deep wisdom – if Tom and Vivienne don’t kill him first.

Peter is the most apparently mythological character, whom we first meet standing on top of a burned-out car, proclaiming lines like, “My soul is wrought to sing of forms transformed to bodies new and strange! Immortal gods inspire my heart, for ye have changed yourselves.” Where does he come from? Where does he go? He feels like a messenger of the Greek gods – or perhaps even a god himself, bored with life in Olympus. For a while, I thought it was Henriks himself playing the character. There’s a naivety present, yet you sense this is a cover for deep wisdom – if Tom and Vivienne don’t kill him first.

For Peter has certain traits, such as a childlike complete lack of filter, which make him perhaps the worst possible person with whom to go through lockdown. However, he’s still likeable, and again, Henriks does a very good job of creating characters with whom you don’t mind being confined. They all seem very real, from Vivienne’s little comic drawings, to Tom’s wrestling fandom (if there’s isn’t a WWE faction called the “Chainsaw Gutfuck Crew”, there should be). She and he are so clearly wrong for each other, by the end of things you’re rooting for them not to fall in love. So if you put a gun to my head and demand a genre, let’s call it a fantastical anti-romance. Yeah, I think I’m fine with that.

How would you describe your style of film-making these days?

Two years ago, I started listening to the podcast “Elder Sign” which introduces listeners to mostly obscure and lesser known, but also some very famous stories that belong into the general category of “weird fiction”. I was fascinated to see how broad the term is, on one hand, and how specific on the other. A “weird” mood, some subdued fantastical elements (or not subdued at all!), some pretty dark philosophy – That’s basically all that connects these stories, but it’s plenty. Lovecraft is as much weird fiction as is E. T. A. Hoffmann and China Miéville. I like to think of my movies as weird fiction, too.

In more concrete terms, I strive to make character-driven, colourful films that, maybe in the vein of fairy tales, contain some horror, some philosophical pondering, fantastical elements and lots of fun. I like dialogue and I also like dream- and musical sequences. Working with actors is what I enjoy most in the filmmaking process. I like film to present something more than reality, even if it’s done by small means. I try to render economical shortcomings irrelevant via stylisation and irony. I want my films to provide questions, not answers in regards to their topics, to ideally provide some food for thought beyond their runtime. Also, my films are handmade, and it doesn’t seem like that’s going to change any time soon.

Where do you want to go from here, and what are you working on now?

Anyone who says the word “professional” a lot is usually an amateur looking for excuses not to make a movie.

We’ve founded a production company for English language horror films this year. It’s called antikyno. Our production office / post-production facility is inside a container by the harbour – very fitting for a shady underground horror film production company, I think. The films we’re making right now (we’ve shot one so far this year and are planning to make a second one in December) are meant to play all the fantastic international horror film festivals and then be released to places like Tubi. We’re producing with very low budgets, drawing from our eleven years of experience in that realm, inspired stylistically by the production scale of most Bergman and Fassbinder movies.

The first film we’ve shot is called “Birthright” and tells the story of a pregnant witch who seeks to get rid of her evil powers as to not pass them on to her daughter. For this, a complicated ritual needs to be performed, which her boyfriend attempts to do for her in a lonely cabin. Things to not go well. The film will, again, be pretty funny and have a lot of heart, but it does also feature buckets of blood, some scares, a frightful mythology and tragedy at the core of the narrative. It’s not yet finished but I’m very much looking forward to watching it myself. Nisan played the lead role during the 8th and 9th months of her pregnancy.

Last year, we’ve started what’s shaping up to become a tradition of staging classical theatre (or, this year, horror theatre with some classical influence) on an almost forgotten Open Air stage in the park close to our flat.This year’s main event is the aforementioned German adaptation of Ryan Fitzgerald’s unproduced script “Shakespeare and the King in Yellow”, a Faustian horror fantasy tale. Very complex affair for a stage play. Today’s rehearsal was chaos. Let’s see how the show turns out to be. Last year, we did “Antigone”, which was a ton of fun. I’d like to do the Oresteia as a trilogy over three weeks next year, if I can get sufficient funding.

Last year, we’ve started what’s shaping up to become a tradition of staging classical theatre (or, this year, horror theatre with some classical influence) on an almost forgotten Open Air stage in the park close to our flat.This year’s main event is the aforementioned German adaptation of Ryan Fitzgerald’s unproduced script “Shakespeare and the King in Yellow”, a Faustian horror fantasy tale. Very complex affair for a stage play. Today’s rehearsal was chaos. Let’s see how the show turns out to be. Last year, we did “Antigone”, which was a ton of fun. I’d like to do the Oresteia as a trilogy over three weeks next year, if I can get sufficient funding.

At the moment I am also writing a 12-part horror-series that we sold as a narrative podcast to the biggest public radio station in Germany. Production starts in October. Then, there is F60 Kamikaze, of course. We will finish that this year. I simply can’t bear having it lying around unfinished any longer. If that means we will have to learn to do a more complicated sound production and color grade ourselves, we will do that. If this year and last year are any indication for the future, there might be more narrative podcast series coming, as well as the occasional ad (those pay really well). We are definitely going to make two horror films a year though. That’s the solid baseline I will adhere to.