I love Tubi. It’s easily the best of the free streaming services, simply for the amazingly broad selection of content present on it. Much of it is not available anywhere else, which makes the presence of commercials tolerable. It’s no exaggeration to say I watch more content there than on all our paid streaming services – Hulu, Netflix, Amazon Prime and HBO Max – combined. It’s particular broad ranging on overseas content. Where else are you going to find for free, the full five hour, thirty-six minute version of Jacques Rivette’s 1994 film Joan the Maid, nestling shoulders with Cannibal Ferox and eighties Polish werewolf movie, Wilczyca? When we did our 31 Countries of Horror feature last October, most of the entries came off Tubi, from Slovenia to Malta.

An example of the worthwhile weirdness to be found within is Lars Henriks’s “Cthulhu Trilogy,” a loosely-connected (more in spirit than plot) series of three very low-budget German movies, which all end up with Lovecraftian overtones. Because when you’re a 21-year-old with no resources or feature experience, why not tackle cosmic horror? I’m not sure what’s more impressive: having the audacity to try, or that the results are… Well, I’m going to err on the side of caution rather than over-hype, and go with “surprisingly decent.” Sure, you’ll never mistake them for that Guillermo del Toro Cthulhu movie we all want to see. Yet, as the old joke goes, if you watch only one movie this year, where a German punk band face off against an Elder God… It almost certainly will be Zeckenkommando vs. Cthulhu.

Henriks has since moved on to make further, not quite as eldritch abomination influenced movies: as the headline of this article indicates, we’re going to get to those in due course. But I got the chance to quiz him about these early films – all the more impressively, while he was at the hospital, having become father to a baby daughter a couple of days earlier! [Congrats to him on that!] Below you’ll find both his answers, lightly edited for clarity, and reviews of the three movies in question.

How would you describe your ‘Cthulhu Trilogy’ overall, to someone who hasn’t seen them?

My “Cthulhu Trilogy” consists of three weird, European no-budget comedies that take Lovecraftian concepts and apply them to absurdist storytelling. They are three very different movies, all of them united in their indie spirit and weird tonal experiments. They will not be for everyone, but they are pretty eager to entertain and I am very happy with them, even when watching them now, seven years later.

Where did your fondness of Lovecraft come from?

In the small town I grew up in we had a very good book store by the train station. They had one clerk who was just a few years older than me, so he must have been around 17 then. We called him Book Basti. He had extremely long, black, greasy hair, glasses and wore a long, heavy leather coat every day, looking gloomy and generally hating the world. He was that book store’s resident expert in horror. When my mom asked him about a good, lesser known horror book for my fifteenth birthday, he recommended a book by another edgy teenager: Lyubko Deresh.

Lyubko Deresh is a Ukrainian author of horror novels, who wrote his first few books when he was only fifteen or sixteen. They were books about the terribleness of living in disillusioned small towns without hope, so that spoke to me just as much as it spoke to Book Basti. Deresh set his first few novels in a Lovecraftian universe, providing his readers with a downright post-modern mash up of horror literature, ethnobotany and psychedelic rock. His book “Kult” blew my mind and remains my favourite novel to this day. That was my introduction to the Mythos. Lovecraft himself came way later.

I think Lovecraft’s ideas lend themselves well to telling stories about rotten small towns and the evil at their core – A trick that Stephen King took from him in “It”, too. In my shitty hellhole of a town, we had a major Nazi problem. I am talking about actual Neo-Nazis, the full-on murderous variety. They targeted alternative youths in particular, so, as a punk rock kid, I was living with a bull’s eye on my forehead. It was scary. They broke into people’s homes and beat them half to death, chased us through woods and parking garages, beat a friend of mine to a pulp with a vodka bottle for refusing to tell them where I was (I had a band back then and we had written a bunch of songs that really angered them, so there would often be groups of armed Nazis looking for me in particular at village festivals and stuff like that). Those were violent times.

I hate small towns and I grew up in a country which has an old, repressed, unspeakable evil at its very core. Of course Lovecraft’s concepts and stories speak to me.

The most infuriating thing about it was the reaction of police and politicians. We called the cops regularly – They never fucking came. After a break-in to the flat of friends of mine, during which Nazis seriously injured a whole group of them, the cops let the Nazis go and arrested the hurt victims. They never apologised and refused to even acknowledge there was a general problem.

A known murderer, released from prison after fifteen years, was organising this militant scene from his shop for Nazi fashion and music. Later, it turned out those guys had deep connections to the National Socialist Underground, a terrorist group exposed a few years ago, which had ties to the German secret service that ran so deep the files documenting all that crap have been locked away for 120 years. The reasoning is their content would “pose a serious threat” to public order here in Germany.

All of this makes me angry, to this day. I am fuming, writing this. I have seen friends destroyed, fucked up for life, by those disgusting pigs and nobody would fucking help us, for years.

I have tried a couple of times to write a movie about that specifically, but I can’t. All that I produce is joyless, sad and angry and I think those films would turn out pretty unpleasant and miss their mark. Deresh’s approach to Lovecraftiana gave me a fun and easy metaphor to tackle that stuff lightly, particularly in Zeckenkommando (which doesn’t even scratch the surface of the horror of it all, but it’s a quirky, funny way of talking about us, how we were back then, back there, without giving the bastards room to also appear in my movie).

I hate small towns and I grew up in a country which has an old, repressed, unspeakable evil at its very core. Of course Lovecraft’s concepts and stories speak to me.

Warum Hans Wagner den Sternenhimmel hasst (2013)

Rating: B

Dir: Lars Henriks

Star: Hubertus Brandt, Ulrich Bähnk, Nika Kushnir, Jens Wesemann

a.k.a. Why Hans Wagner Hates the Starry Sky

This is a real curio, which starts off as a charming light romance of quirky characters, before becoming… something radically different. It’s the kind of dramatic shift that a film is rarely able to pull off, yet somehow works. Hans Wagner (Brandt) is a socially inept shut-in, reliant on self-medication for the barest semblance of functionality, but is forced out of his shell when he falls for a local supermarket cashier, and is befriended by homeless man Hobbit (Bähnk). So far, so endearingly normal. Things change when he’s visited in his house by a fairy who offers to grant Hans one wish. Of course, as anyone who has played D&D knows, wishes tend to get fulfilled in unsatisfactory ways, and come with a price. Both those occur to Hans, as part of an occult plot by Gregor (Wesemann), to crack open a portal and let the Old Gods back into this world.

Made by the 22-year-old Henriks on a budget of just 1,500 Euros, it’s testament to making a little go a very long way, and how important it is to have a strong idea and a good script, when your resources are limited. Clearly, you’re getting no appearance by Cthulhu at that price, yet the film still generates the right atmosphere in other ways. For example, the frequent use of voice-over narration enhances the feeling that you’re watching a fairy-tale. Yet the horror elements are brought splendidly to the fore, when the narrator describes what someone being eaten alive by the cultists is feeling. We also care about the characters, in particular Hans, because of the effort put in during the first half to make them sympathetic. He may be emotionally stunted and awkward; that just makes Hans all the more human, and you want him to find happiness and true love. I thought I knew where the movie was going, when he meets Amelie (Kushnir), who is hardly less of a klutz. Henriks clearly had other ideas.

Made by the 22-year-old Henriks on a budget of just 1,500 Euros, it’s testament to making a little go a very long way, and how important it is to have a strong idea and a good script, when your resources are limited. Clearly, you’re getting no appearance by Cthulhu at that price, yet the film still generates the right atmosphere in other ways. For example, the frequent use of voice-over narration enhances the feeling that you’re watching a fairy-tale. Yet the horror elements are brought splendidly to the fore, when the narrator describes what someone being eaten alive by the cultists is feeling. We also care about the characters, in particular Hans, because of the effort put in during the first half to make them sympathetic. He may be emotionally stunted and awkward; that just makes Hans all the more human, and you want him to find happiness and true love. I thought I knew where the movie was going, when he meets Amelie (Kushnir), who is hardly less of a klutz. Henriks clearly had other ideas.

I think the most impressive aspect is the ability to pull off the transition into darker, apocalyptic territory, while bringing the audience along. I think it’s the way the film creates a world that is off-normal, for example, Hans breaking into a well-choreographed music video on the way to the supermarket, or a cupboard being a portal to another world, in a Narnian way. Once you’ve made that leap, this gets the viewer to a point where it becomes much easier to accept the concept of horrific deities that have slumbering, waiting their opportunity to return. It’s just another wrinkle in this reality. I do feel Henriks kinda painted himself into a bit of a corner with the scripting, and the resolution which follows is a little unfulfilling because Hans doesn’t play much part in it. However, considering I spent the first half wondering how this could possibly be in the slightest bit Lovecraftian, all I can say is: well done.

Were the three films always intended as a trilogy, or was that something which came later?

It happened organically. Hans Wagner was my attempt at making something that felt like a cinematic version of what the novel Kult did – Of course without really adapting it and without any money. (I would very much like to do that now, but haven’t found the needed budget yet) I shot Hans Wagner back in my shitty small town, in the children’s acting school that I had attended, using the handmade stage designs the children had made for an added absurdist layer. In a way, all three films of the Cthulhu trilogy are navel gazing – though very decidedly not overtly autobiographical. When I decided to make another film like Hans Wagner and set it in the same world, with a character even re-appearing, it was clear to me that I wanted to make at least a third one. Being a megalomaniac in my early 20’s, I had plans for a whole cinematic universe, but the lack of budget stopped me.

I read you were largely inspired into film-making by the German splatter films of the nineties (and how bad they were!) Which ones were particularly “influential”, and what did you take from them?

I wanted to become a filmmaker even when I started to speak. My very first question, according to my parents, was “How can I make a movie?”, which my Dad spent my childhood to research with me. I had empty film reels on which I drew primitive animation clips when I was five, running them through a self-made film projector made from toilet paper rolls and a bedside lamp. I had my first camcorder with which I made stop motion dinosaur films when I was six and won my first film prize for one of those when I was nine. When it came to film-making, there was no stopping me. Until there was.

When it came to film-making, there was no stopping me. Until there was.

The German film industry is completely centralised and basically state-run at this point. Films that interest me (genre stuff, obviously, anything involving fantastical elements) generally can not get produced here. I realised this as a young teenager and was desperately looking for ways to still fulfill my life’s ambition, despite being born in a country that had no place for that.

During this time I came across the German amateur splatter scene. These were filmmakers from Germany who started making their own splatter films in the late 80’s and early 90’s. Back then, additionally to the rigidly centralised film industry, foreign films, too, were heavily censored. In fact, to this day, despite having eased up considerably, German film censorship is internationally known for being the strictest among more or less liberal Western countries. Back in the 90’s, countless classics of cinema were outright banned over here. Owning and distributing The Evil Dead or Dawn of the Dead, for example, could land you in prison. So, a couple of enthusiasts who just wanted to watch movies like they had seen in horror magazines, started making their own self-made splatter effects. These filmmakers were proudly amateurish and the movies to a large part horrendous, but they provided mindless fun to a teenage me, and we would watch them at parties.

Probably the most important film to emerge from this scene (even though transcending it in many ways) is Olaf Ittenbach’s “Premutos”, recently re-released in North America by Unearthed films – I wholeheartedly recommend having a look at the German “Braindead”! (You can watch it on Tubi!) These films showed me that it was possible to make fun genre films people would want to see even without a budget. “Premutos” less so, because that one did have a slight budget. But Ittenbach’s earlier, truly no-budget efforts, like “Burning Moon” and “Black Past”, as well as the awful “Violent Shit”: if THAT piece of crap can play in Underground Cinemas in New York, anything I make could, too! Or the more competently awful “Violent Shit 3”.

I would never have attempted making movies without budgets – making genre films that interest me in Germany – if it wasn’t for those horror veterans. I copied their spirit while, unlike most of them, casting professional actors and putting less of an emphasis on shock value. They encouraged me to pursue film-making at all, simply by proving it was possible to make films on your own and against the embittered opposition of this state – and even to make money in the process.

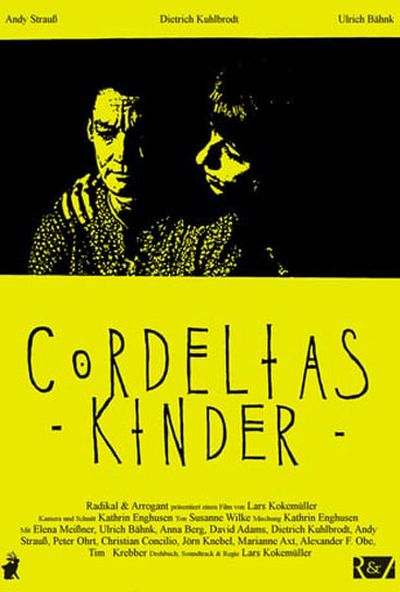

Cordelia’s Kinder (2015)

Rating: C+

Dir: Lars Henriks

Star: Elena Meißner, David Adams, Anna Berg, Ulrich Bähnk

a.k.a. Cordelia’s Children

To some extent, this could almost be a Lovecraftian German version of Parasite, with the very ugly truth behind the facade of a nice, middle-class family gradually coming to the front. Cordelia (Meißner) and her family are trying to cope with the death of her husband, who was murdered after going out to buy toilet paper – this was made well before COVID, so this quest is not a metaphor for anything. He, in ghostly form, hangs about the house, passing sardonic comment on their lives. Meanwhile, her two teenage children, Thomas (Adams) and Julia (Berg) have concerns of their own. The former is coming to terms with being gay, while the latter may be a contract killer in the making, and suspects her mother of involvement in her father’s death. Oh, and there’s a door leading into a dark abyss, which was always locked when Dad was alive. Thomas is experiencing lurid nightmares, ordering him to close the door again or “gods” might come through it.

Basically the entire film takes place in the house ‐ it belonged to the director’s parents, and was shot over a few weeks between them moving out, and the new residents arriving. This helps generate a claustrophobic, cloying atmosphere for the family drama. It’s mostly in black and white, with occasional bursts of colour, such as Thomas’s dreams, though there is no consistent logic to this. It’s at its best when contrasting the banal world of everyday life with the batshit crazy elements of this dysfunctional family. For example, when Cordelia hires her daughter to kill the two cops investigating her husband’s murder, while simultaneously ordering her to clean up her room. Or Thomas going in to tell his sister dinner is ready, unfazed by the fact there’s a half-naked, tortured man tied to a chair there – he mostly seems put out by the fact it’s his chair being used.

Basically the entire film takes place in the house ‐ it belonged to the director’s parents, and was shot over a few weeks between them moving out, and the new residents arriving. This helps generate a claustrophobic, cloying atmosphere for the family drama. It’s mostly in black and white, with occasional bursts of colour, such as Thomas’s dreams, though there is no consistent logic to this. It’s at its best when contrasting the banal world of everyday life with the batshit crazy elements of this dysfunctional family. For example, when Cordelia hires her daughter to kill the two cops investigating her husband’s murder, while simultaneously ordering her to clean up her room. Or Thomas going in to tell his sister dinner is ready, unfazed by the fact there’s a half-naked, tortured man tied to a chair there – he mostly seems put out by the fact it’s his chair being used.

However, the above suggests a more even tone than the film ever manages to achieve. At one point, it basically becomes a music video, with Thomas and his boyfriend lip-synching enthusiastically, and doesn’t fit as well as a similar scene did in Henriks’s previous film, Hans Wagner. This is definitely a movie where you just have to accept whatever it throws at you, and that it may or may not make sense. The ending, in particular, just… kinda… occurs. Though apparently, no well-equipped German kitchen is complete without a convenient canister of petrol to hand. That said, if the brooding sense of dread never gets an adequate payoff, the performances are better than I expected. Or perhaps it could be more that the dysfunctional nature of these characters, helps excuse any rough edges i.e. Adams, fir whom this is his only IMDb credit. It does feel like the director was being pulled in a few too many directions, likely an inevitable result of all the hats Henriks wears in this production. Yet enough of them were successful – or at least failed in interesting ways – to sustain my interest.

You clearly love horror, but the films here all start elsewhere i.e. rom-com or family drama, before shifting. Why did you do that, rather than making a “pure” horror movie?

When I started out, I was too arrogant to consciously do anything conventional. I had read a Fassbinder quote that went “I want to be to film what Shakespeare was to theatre. There shall be a before and after me.” I wanted to do new things, to pursue uncharted territory in terms of storytelling. Also, I knew very well that I did not have the means to pull off a story I wanted to tell, in a way that would be conventionally convincing. I chose irony as a tool to make the obvious flaws in production value acceptable to audiences. I wanted everything to feel like it was meant and needed to be exactly the way it was. I also wanted to provide entertainment, and surprising the audience seemed like a good (and free!) way of achieving that, so genre-bending was what I was going to do back then.

Lastly, I might be unable to suppress my particular brand of humour enough to make a film full-on scary. I’m okay with that now. We founded a production company for English language horror films this year and are going to make two micro budget features a year – the first one is already shot. On set, I frequently found myself re-arranging scenes to make them more funny. That’s just how I tick. As long as the central drama is treated seriously, I like to laugh during scary films, ideally with the characters, getting attached to them, in order then to really care about what happens in their story.

Another common theme is the (largely unexpected) musical numbers in each film. Where do those come from?

The only job other than filmmaker I ever seriously considered was musician. I played in punk bands since I was 13, I was touring the country with my electro punk band E123 for seven years before we disbanded, I am still active in a post-punk combo, working on an album and making the soundtracks to almost everything I direct. Music is my other way of expressing myself and I find it helps getting across the tone I want greatly to include lots of it.

You made your first feature, Hans Wagner, with almost no money. What was the biggest challenge you faced?

I naively threw myself into that situation, got a bunch of people attached, thus giving myself no way out, and we just did it.

Honestly, Hans Wagner was comparably easy. I was so hapless back then. The script is un-filmable on a 1500€ budget. I adapted a novel I had written as a teen (you guessed it, inspired by teenage author Lyubko Deresh) into the script without thinking about how I would pull it of, because thinking about that gave me writer’s block – because what is anyone going to pull off on that budget? So, I naively threw myself into that situation, got a bunch of people attached, thus giving myself no way out, and we just did it.

I had access to professional actors because I was one myself and all my friends were actors, I had a student film crew who got equipment for free from the university, so all of that worked out easy enough. I think there’s a dialogue scene between Hans and Hobbit, on a bench in front of the supermarket, during which it started to snow lightly. The second I said “cut” after our last take, a veritable snow storm started and didn’t end for the rest of the day. It was late March. The snow didn’t melt until April. The shoot would have fallen apart if we hadn’t finished that scene that second.

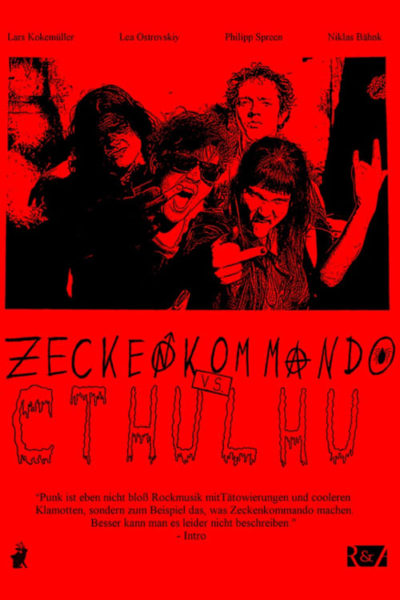

Zeckenkommando vs. Cthulhu (2015)

Rating: B-

Dir: Lars Henriks

Star: Lars Henriks, Lea Ostrovskiy, Philip Spreen, Niklas Bähnk

By this, my third Henriks film, I was beginning to get a better handle on what to expect. So I was not, at all, surprised when this opened with a music video. Though in this case, there was a good movie world explanation, it being a creation of the self-proclaimed best, most hardcore punk band in Lower Saxony, Zeckenkommando. If only the world would recognize their talent. Perhaps it’d help if the members spent less time, frankly, dicking around e.g. heading off to the woods for the weekend to take magic mushrooms. They face an existential threat, with the sale of the building where they rehearse to a mysterious investor. They find it’s part of a conspiracy covering both the media and politicians in their town, with a cult group preparing to complete an occult ceremony which had begun in World War II. Can four punks stop them awakening the dormant Elder God Cthulhu from its Pacific slumber?

Again, by “what to expect”, I was unsurprised when the first half passed without the slightest mention of any Lovecraftian eldritch horrors. You’re basically hanging out with Kalle (Henriks), Xena (Ostrovskiy), Flash (Bähnk) and Titus (Spreen), in their everyday, entirely work-free lives. [Germany must have really good unemployment benefits…] Considering how little actually happens in this phase, it’s still amusing enough, basically an extended phase of character building, that bonds you to the band. I think this may be Henriks’s best talent as a filmmaker: creating people with whom you want to spend time. It was also fun to spot returning actors, such as Elena Meißner from Cordelia’s Kinder, who shows up as the band’s landlady.

Again, by “what to expect”, I was unsurprised when the first half passed without the slightest mention of any Lovecraftian eldritch horrors. You’re basically hanging out with Kalle (Henriks), Xena (Ostrovskiy), Flash (Bähnk) and Titus (Spreen), in their everyday, entirely work-free lives. [Germany must have really good unemployment benefits…] Considering how little actually happens in this phase, it’s still amusing enough, basically an extended phase of character building, that bonds you to the band. I think this may be Henriks’s best talent as a filmmaker: creating people with whom you want to spend time. It was also fun to spot returning actors, such as Elena Meißner from Cordelia’s Kinder, who shows up as the band’s landlady.

The director has compared this to a Scooby-Doo adventure, and I can see the similarities. It must be said, the villains here are more than a bit crap, and hardly represent the world shattering peril you would expect. Even when they summon Cthulhu, it’s a largely underwhelming eldritch horror we see, lurking in the shadows. “I thought it’d be bigger,” mutters a cult member. This kind of self-awareness helps counter the budgetary constraints. See also the way the band sends out a call to arms against the cult on social media… ending with an exhortation to like, share and subscribe. Or the way they can’t stop laughing at the cultist with a lisp.

This reminded me a bit of a New Zealand movie, made the same year: Deathgasm, with punk here replacing heavy metal. That’s especially true at the end, where music – in the form of a “Cthulhu lullaby” – proves a way for Zeckenkommando potentially to send the deity back to its torpor. If only their guitarist could master that tricky H minor chord, and if internal romantic tensions within the group (such as Kalle wanting to make a sex-tape with Xena) don’t tear the friends apart. Such are the perils of life as a wannabe rock star. Well, and potentially becoming part of a world enslaved to a malevolent god.

For Cordelia’s Kinder, you went to black and white… mostly. Why did you take that approach?

When thinking about what my next project should be, I watched a music video by a German rapper I liked. It was in black and white and had a kind of nasty, mean spirited atmosphere, hopeless, raw and angry, and I wanted to make a film like that. That was the first impulse, so the black and white was part of it from that moment on. My DoP and editor Kathrin didn’t like the idea too much, and insisted on breaking that with a few splashes of color. I hadn’t seen it done that way too much before, so I liked the idea. I wanted the film to capture a very specific mood, and in my head that mood was tied to a presentation in black and white.

In Zeckenkommando vs. Cthulhu, you took on the main role yourself. Was that a choice or out of necessity?

I studied acting and played one of the leads in the Australian teen sitcom “In your Dreams” for two seasons, back when I made the Cthulhu trilogy. So acting in one of the movies myself wasn’t a far-fetched idea – though I didn’t really want to do it, because I felt I just had one job too many during the shoot that way. Still, it wasn’t easy to quickly find an actor who got the script, was willing to dye their hair, could sing and believably portray the specific kind of small town punk doofus I had in mind for Kalle. So when I didn’t find one, I did that myself.

I’ve done that in two other instances, both film projects failed in my eyes, largely due to me not being able to properly direct when acting. We finished those films, I’m just really unhappy with them. We recently shot the first one of our English horror films and I played the lead again, after years of not acting, because we’re such a well-rehearsed team now, my DoP Christian Grundey, my producer and co-lead Nisan Arikan, and I, that I could trust everything to work out behind the camera even when I was in front of it. And it worked. I’m very proud of that film and can’t wait to share it with the world soon.

Looking back on the trilogy now, what do you think of them?

I’m proud of them. There’s lots of unique little details in there that make me happy.

Every now and then something happens with those movies and I have to watch them again. Recording bonus commentary for an American BluRay release, attending a screening, stuff like that. I am surprised, every time, by how much I like them despite all their obvious flaws. I was an inexperienced filmmaker with no budget and no support at all, and that shows, but I feel like the mood I was going for comes across and they are generally a good time, at least to me. I’m proud of them. There’s lots of unique little details in there that make me happy. They are also, due to being shot at places I had easy access to, places from my personal life, and me having full control over the scripts – for better or worse – very personal and intimate to me. Whether or not they are very good, hey are very much a result of who I was when I made them.

If you could adapt any Lovecraft story, money no object, which one would you make?

I came to Lovecraft a long after discovering the Mythos in other author’s works, but I really love his stories a lot. There are many I would like to adapt, not least of all because they are basically bundles of tantalising ideas that need to be fleshed out. Lots of plot and character work still to be done, and I love doing that kind of stuff. I am fascinated by the “Dream Quest” saga, which to me reads like a cave drawing version of “Sandman” and could surely the fleshed out into something that feels similar to the recent Audible adaptation of that graphic novel. I would love to do something with that.

“Shadow over Innsmouth” is also a constant source of fascination to me. Probably the one with the most cinematic plot in place already, and a lot possibly still to be added in terms of characters and mythology. “Cats of Ulthar” I would love to make as a stop motion animation film. “Pickman’s Model” has a great setting for a very fun slasher / creature feature. I need to stop now, since you asked for ONE story and I’m in the process of rattling off ideas for every Lovecraft story that crosses my mind! I’d be excited to adapt any one of them, as well as coming up with new stories set in his sprawling universe.

In Part 2, we talk about and review Lars’s post-Cthulhu work, including Bearkittens, Performaniax and Covid Metamorphoses.