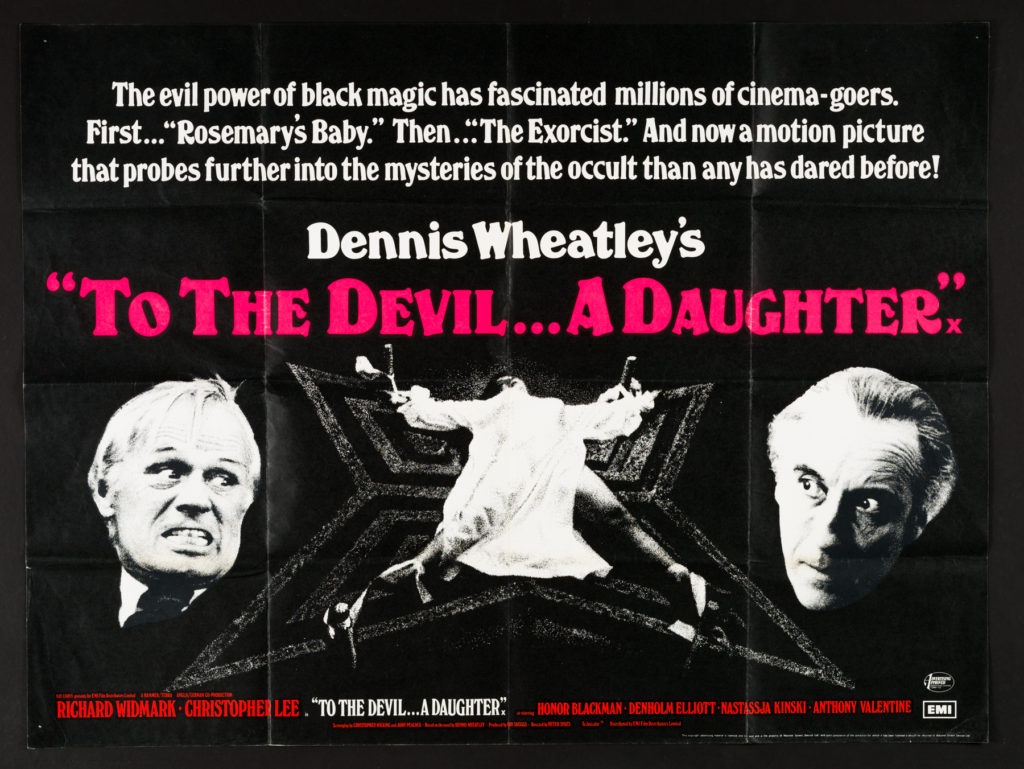

Rating: B

Dir: Peter Sykes

Star: Richard Widmark, Christopher Lee, Nastassja Kinski, Anthony Valentine

After Peter Cushing’s somewhat ludicrous farewell to Hammer in The Legend of the 7 Golden Vampires, it’s now time for Lee’s swan-song. Though certainly problematic, and another troubled production, given the issues, I’d say it’s remarkable the end result is as largely effective as it is. Lee definitely gets a role with fitting gravitas on which to go out, and the supporting cast are the equal of any Hammer movie. Despite perception and poor reviews, it was a box-office success – quite the reverse of previous Dennis Wheatley adaptation, The Devil Rides Out. The problem from Hammer’s point of view, was that their production agreements meant the profits ended up going to partners EMI and German company Terra Filmkunst instead, since they provided the funding.

Wheatley was also thoroughly unimpressed, according to friend Lee. The writer reportedly said of the movie, “This is disgusting, obscene, has no relationship to my book. It’s outrageous and disgraceful.” Well, I wouldn’t have said it was that good… He vowed never to let Hammer adapt any more of his works, though this ended up moot, since Daughter proved the studio’s final horror film. But I’m going to call it the best of their three Wheatley adaptations. It may be a mess, but it’s a far more entertaining mess than the rather dull Devil, and definitely kicks the arse of The Lost Continent. These Satanists have a definite plan, decades in the making, and will stop at nothing to carry it out. Elements are still shocking, 35 years later; indeed, some perhaps more so than at the time.

After considering names including Ken Russell and Nicholas Roeg, the studio went with Peter Sykes, who had previously directed Demons of the Mind for them. He considered the book close to unfilmable, and he may have been correct. For after two previous writers took a crack, it ended up with Gerald Vaughan-Hughes having to do an uncredited rewrite on set, handing Sykes the pages each night for the following day’s shooting. Sykes did bring Kinski on board, after seeing her debut, in Wim Wenders’ Wrong Move. There were at one point plans to bring her father, Klaus, on as well, but he proved unavailable. Widmark instead got the role of occult writer John Verney. But perhaps he was possessed by the ghost of Klaus, for Widmark’s behavior was apparently a real problem during shooting.

After considering names including Ken Russell and Nicholas Roeg, the studio went with Peter Sykes, who had previously directed Demons of the Mind for them. He considered the book close to unfilmable, and he may have been correct. For after two previous writers took a crack, it ended up with Gerald Vaughan-Hughes having to do an uncredited rewrite on set, handing Sykes the pages each night for the following day’s shooting. Sykes did bring Kinski on board, after seeing her debut, in Wim Wenders’ Wrong Move. There were at one point plans to bring her father, Klaus, on as well, but he proved unavailable. Widmark instead got the role of occult writer John Verney. But perhaps he was possessed by the ghost of Klaus, for Widmark’s behavior was apparently a real problem during shooting.

The story describes the completion of a decades-long plot by excommunicated priest Father Michael Rayner (Lee). He has been working to turn a young woman, Catherine Beddowes (Kinski) into a vessel for the demon Astaroth, through a combination of sacrifice and ritual. However, her Satanist father (Denholm Elliott) is having rather belated second thoughts about his pact with the Devil, and diverts Catherine into the care of Verney. This sets up an occult battle between the priest and the writer for Catherine’s soul and the fate of the world. Father Michael uses black magic to locate his victim, and make her do his bidding, while Verney tries to counter these efforts, and discover where and when the ceremony will take place. As in The Devil Rides Out, their battle is largely at a distance, protagonist and antagonist only meeting physically in the final scene.

There’s no doubt this was inspired by its Satanic predecessors. These began with Rosemary’s Baby in 1968, hit blockbuster status with 1973’s The Exorcist, and this just beat The Omen to British cinema screens by a couple of months. It’s not as coherent as those, and the fact it was basically being made up as they went along is often obvious, with scenes that never get explained, and others which may or may not take place in the real world. Yet, I feel, this enhances the nightmare quality, giving it a plot illogic which would probably have been lauded if this was directed by Dario Argento. A good bit of the credit for that has to go to Paul Glass’s discordant, almost atonal score, which sounds like someone bored a hole to hell, and dropped a microphone through it.

Admittedly, the final confrontation is woefully bad. Lee said it “completely ruined the end of the movie”, and even the director admitted, “We tried and tried and tried and we couldn’t make it work.” Producer Michael Carreras went to partners EMI, and asked for more money to fix it, but was told it was fine. It isn’t. Verney spouts some previously unheard nonsense about flint and the blood of a disciple, and chucks a rock at Rayner, who then vanishes in a puff of plot logic. The writer then drags Catherine from the altar in a slew of bad optical visual effects, and off to safety. Hammer often had problems with their endings, tending heavily towards the abrupt. So did Wheatley (I seem to recall one book where a character randomly discovered a hand-grenade…). Put them together and disaster is almost inevitable.

Then there’s the underage elephant in the room. Unlike just about every nude scene in cinema history, Nastassja Kinski’s full-frontal exposure is curiously absent from the Internet. NK had a habit of changing her date of birth as convenient; even now, some sources give it as 1959 or 1960. But it’s generally agreed to be January 24, 1961. Meaning, when the film was shot in September 1975, the actress writhing around in sensual ecstasy, and later leaving even less to the imagination, was aged… fourteen. Hence the scene’s Internet absence, I imagine. About the closest you’ll find is a video cover featuring a shot from the finale… onto which the distributors have carefully painted a red nightgown. [Asked about the nudity in a 1996 interview, Nastassja said firmly: “Those scenes were not me.” Surrrrre… In her defense, she may have been referring to some other sequences, like the “reverse birth” in which a demonic foetus crawls into her]

Then there’s the underage elephant in the room. Unlike just about every nude scene in cinema history, Nastassja Kinski’s full-frontal exposure is curiously absent from the Internet. NK had a habit of changing her date of birth as convenient; even now, some sources give it as 1959 or 1960. But it’s generally agreed to be January 24, 1961. Meaning, when the film was shot in September 1975, the actress writhing around in sensual ecstasy, and later leaving even less to the imagination, was aged… fourteen. Hence the scene’s Internet absence, I imagine. About the closest you’ll find is a video cover featuring a shot from the finale… onto which the distributors have carefully painted a red nightgown. [Asked about the nudity in a 1996 interview, Nastassja said firmly: “Those scenes were not me.” Surrrrre… In her defense, she may have been referring to some other sequences, like the “reverse birth” in which a demonic foetus crawls into her]

As noted, Lee gets help from a solid supporting cast. Leading the familiar names is Honor Blackman as Varney’s agent, who meets an unfortunate fate at the pointy end of a steel comb. Frances de la Tour – still acting, recently seen as Enola Holmes’s grandmother – plays a Salvation Army worker, and Brian Wilde, veteran of sit-coms like Porridge and Last of the Summer Wine, is a library attendant in the “Black Room”, where the church keeps its forbidden texts. But it’s Lee’s world: everyone else is just operating by his kind permission. The true depths of his depravity is apparent in the way Father Michael truly appreciates the excesses required for his plan to work. He may not have got to don the capes and fangs for his finale, but this is definitely one of Lee’s most memorably evil roles.

This review is part of Hammer Time, our series covering Hammer Films from 1955-1979.