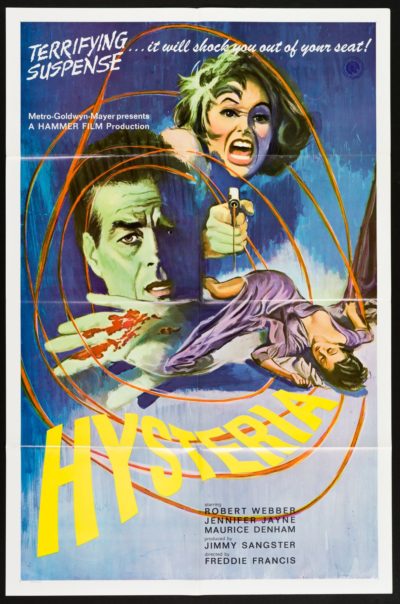

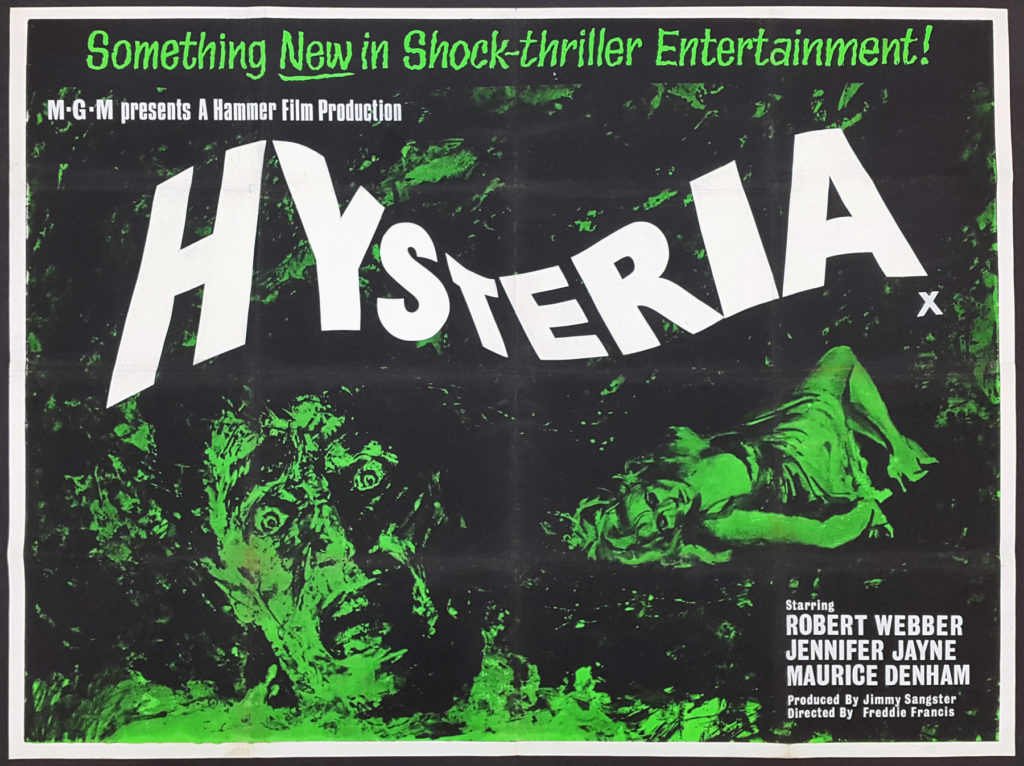

Rating: D+

Dir: Freddie Francis

Star: Robert Webber, Lelia Goldoni, Anthony Newlands, Maurice Denham

Full disclosure: this one was watched while “tidying up.” And I use quotes, since the tidying I was doing involved the leftovers from a wine-tasting we’d had the previous Saturday. This means my thoughts and feelings about the movie will probably become a little vaguer, shall I say, as we proceed through the narrative. Which may well work to the film’s benefit. For this is one of those twisty, psychological thrillers where I inevitably find myself thinking of far easier ways that the perpetrators could have achieved their intended aim. Anything which distracts from that – in this case, the contents of more than one partial bottle of wine – is not a bad thing.

In this case, the victim is “Chris Smith” (Webber). Quotes used here, since he has forgotten his real name, and everything about him, following a road accident. Assisting his recovery is Dr. Keller (Newlands), with the aid of a mysterious benefactor, who not only pays for Chris’s treatment, but sets him up in the awanky London penthouse of a partially-completed building, when he’s ready to enter the real world again. About the only clue to Chris’s identity is a newspaper clipping of a beautiful woman, so he engages the services of private detective, Hemmings (Denham) to track down the woman. At first, it appears she was a model, who was stabbed to death in the very apartment where Chris is now living. What are the odds?

But then he sees her driving a sports car, and it turns out, she is Denise James (Goldoni), the rich widow of the man responsible for Chris’s accident, and also his benefactor. However, that doesn’t solve Chris’s other problem – and stop me if you’ve heard this before in… oh, I dunno, just about any other Hammer psychological thriller, except for Cash on Demand. For he is being plagued by bizarre incidents and hallucinations, such as a corpse that vanishes, bloody knives appearing, and voices raised in argument, coming from the empty floor beneath his penthouse. Is Chris going insane? Or is someone trying to drive him that way? You will already know the answer to that question – if, again, you’ve seen just about any other Hammer psychological thriller, except for Cash on Demand.

But then he sees her driving a sports car, and it turns out, she is Denise James (Goldoni), the rich widow of the man responsible for Chris’s accident, and also his benefactor. However, that doesn’t solve Chris’s other problem – and stop me if you’ve heard this before in… oh, I dunno, just about any other Hammer psychological thriller, except for Cash on Demand. For he is being plagued by bizarre incidents and hallucinations, such as a corpse that vanishes, bloody knives appearing, and voices raised in argument, coming from the empty floor beneath his penthouse. Is Chris going insane? Or is someone trying to drive him that way? You will already know the answer to that question – if, again, you’ve seen just about any other Hammer psychological thriller, except for Cash on Demand.

To be fair, the air of jaded cynicism, which observant readers may have noted in the previous paragraph, is likely partly due to the concentrated nature of this project. The first of Hammer’s films in the genre, and its closest cousin, was probably The Full Treatment, which I reviewed in May. This means that in five months, I have seen multiple movies in the genre which actually came out over the space of five years. If it doesn’t entirely excuse the lazy way writer Jimmy Sangster recycles the same components, time and again, it likely makes understandable the studio’s willingness to keep mining the seam. Though it appears this wasn’t a success, suggesting the general public in the sixties were getting bored of them, despite the greater lag between entries.

The early stages are where its at it’s most effective, though my wine-soothed state didn’t entirely stop me asking questions. Such as, who furnishes an apartment with a pair of toucans? [Birds which no-one ever seems to feed or take care of] Or whether Denise’s towering hair-do had to be cleared as a potential threat to incoming planes at Heathrow. But it manages a fairly level keel, with American import Webber (best known as Juror #12 in 12 Angry Men) managing to be relatively sympathetic; I also enjoyed veteran character actor Denham’s performance. However, about the half-way mark, there’s a lengthy flashback sequence, telling us what led up to the accident, and including one of the least-convincing “falling over on a flat surface” moments in cinema history.

It weakens audience sympathy, showing us that Chris was a bit of a cad, having an affair with a married woman in Paris (her husband is played by Kiwi Kingston, who was the monster in The Evil of Frankenstein), then dumping the girl who helps him get out of that mess. I’m not quite sure what the point of the whole exercise is here. Though it does play into his post-accident behaviour, I can’t help thinking, as with the rest of the plot, there were simpler methods available to reach the same ends. It does suggest he’s not such a patsy as the perpetrators seem to think, and as it ends up, may well be playing 4-D chess, when they’re playing draughts.

It does mitigate the whole “amnesia” angle; almost always a cop-out, here, it’s not particularly relevant. However, I wasn’t satisfied in the slightest with the ending, where all is revealed, and morality triumphs. While I can’t say it “cheats,” as such, it does seem to rely on a lot of information to which the audience was not party. Despite the title (an interesting choice, given at the time, the term was largely reserved for female traits), everyone seems to react rather too calmly, almost as if Chris wasn’t the only one on mind-altering drugs. I mean, if I discovered a dead body in a bathtub, at least a little hysteria would seem appropriate. Maybe sixties’ nurses were made of sterner stuff. Similarly, the bad guys accept their fates with a phlegmatic resignation that hardly provides the pulse-pounding climax the film needs.

This was Francis’s last foray into the genre, after having directed Paranoiac and Nightmare from Sangster scripts. Despite a psychedelic spiraly opening, with the bulk of the action taking place in and around the penthouse, there are not many opportunities to express style here. Even Chris’s freakouts seem restrained, not much more than closeups of his sweaty face. Its lack of success likely is what caused Hammer to take a bit of a break from the field, not producing another full-blown psychological thriller for five more years, until 1970’s Crescendo. After this underwhelming entry, I think I’m probably fine with that, and look forward to a respite from watching them.

This review is part of Hammer Time, our series covering Hammer Films from 1955-1979.