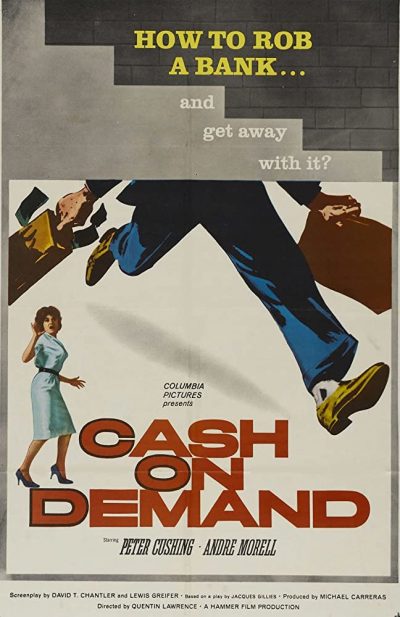

Rating: B-

Dir: Quentin Lawrence

Star: Peter Cushing, André Morell, Richard Vernon, Norman Bird

Hammer returned to television for their source material, as they had done for the likes of The Quatermass Xperiment. This had originally been produced as an episode of the Theatre 70 drama series, called “The Gold Inside”, broadcast in September 1960. Written by New Zealand author Jacques Gillies, prolific TV director Lawrence had also helmed that, with Morell and Vernon playing the same roles as they did in the movie. [The IMDB says Lawrence was part of the Manhattan Project, which seems… unlikely?] However, the part of uptight bank manager Mr. Fordyce, played here by Cushing, had originally been Richard Warner. The result is something which is unusual in a number of ways, not least for being Hammer’s sole movie with a festive theme.

It’s often compared to A Christmas Carol, with Fordyce as a Scrooge-like character, who has little time for festive shenanigans, like the party being planned by his employees. He is shown the error of his ways by the humbling actions of Colonel Gore-Hepburn (Morell), a bank robber without a gun. But I feel it’s almost like a genteel British version of Die Hard. After all, they both take place just before Christmas, and are about a daring robbery, executed by a smart and charismatic criminal. The resonance struck me in particular with this exchange:

Fordyce: The opinion of a common thief is of no interest to me.

Gore-Hepburn: I flatter myself I am a rather uncommon thief.

That immediately reminded me of these lines from Die Hard:

Holly: After all your posturing, all your little speeches, you’re nothing but a common thief.

Hans: I am an exceptional thief, Mrs McClane.

Cash on Demand takes place on December 23, unfolding more or less in real time, beginning with the opening of the Haversham branch of the City & Colonial Bank. Fordyce has been its manager for fifteen years, ruling things with a iron hand. This is made clear early on, when he berates veteran deputy manager Pearson (Vernon), who has been there for more than a decade, over the poor state of a pen on the counter: “The nib’s completely corroded. It obviously hasn’t been cleaned or examined for weeks. This isn’t a post office, you know…” A minor accounting error then causes Fordyce to threaten Pearson with the sack, firmly establishing the manager’s credentials as a bit of a dick.

Cash on Demand takes place on December 23, unfolding more or less in real time, beginning with the opening of the Haversham branch of the City & Colonial Bank. Fordyce has been its manager for fifteen years, ruling things with a iron hand. This is made clear early on, when he berates veteran deputy manager Pearson (Vernon), who has been there for more than a decade, over the poor state of a pen on the counter: “The nib’s completely corroded. It obviously hasn’t been cleaned or examined for weeks. This isn’t a post office, you know…” A minor accounting error then causes Fordyce to threaten Pearson with the sack, firmly establishing the manager’s credentials as a bit of a dick.

The everyday routine is interrupted by the arrival of Gore-Hepburn, who introduces himself as an inspector appointed by the Home and Mercantile Bankers company, who insure the branch. He’s apparently there for a spot check, to make sure proper security procedures are being followed. However, after he’s alone with Fordyce, the manager’s phone rings, and he hears the terrified voices of his wife and child on the other end, begging Fordyce to “do whatever he says”. Gore-Hepburn then reveals he is there to relieve the strongroom below of multiple company payrolls, and if Fordyce doesn’t co-operate, and also ensure the rest of the staff are kept ignorant of proceedings, the day will end very badly for his family.

Fordyce initially tries to resist, but is soon beaten down – both physically and psychologically – and follows his visitor’s demands meekly thereafter. It’s a well-thought out plan, which has Gore-Hepburn’s “luggage” brought into the office, then Fordyce and the oblivious Pearson open the vault, before the latter leaves, allowing the thief to replace the contents of his cases with £93,000 in cash being held in the strongroom. He exits, warning Fordyce that the family will remain hostages for an hour, to ensure Gore-Hepburn is able to make a clean getaway, and there must be no attempt to alert the authorities. However, Pearson, unexpectedly following protocol, has called up Home and Mercantile to confirm the inspector’s identity. The results of that call mean the cops are already on the way.

This is where the Christmas Carol comparisons kick in. Fordyce is suddenly at the mercy of his staff, and the fate of his family hangs in the balance, first on their goodwill, and then an even more unexpected festive Samaritan. It does still seem a stretch, and it’s vague as to the specific lesson Fordyce is supposed to have learned. If anything, this is the kind of incident which will make him more suspicious and less trusting in future: fool me once, etc. There is just one location and only three significant characters in its crisp 80-minute running time (it was cut down sharply for US release, some versions running as short as an hour), making the origins as a play, albeit one written for TV, clear. Though they are never obvious, Lawrence using the limited sets to create a claustrophobic atmosphere, from which the film rarely escapes.

Both leads, who had partnered up previously as Holmes and Watson in The Hound of the Baskervilles, are excellent. Gore-Hepburn is exactly the sort of charismatic character you can see pulling this off. I was reminded of classic Fawlty Towers episode, “A Touch of Class”, in which Basil falls victim to the fake Lord Melbury, who couldn’t possibly be a conman. Here, Pearson tells the robber, “If I may say so, sir, you don’t look much like a gunman,” to which Gore-Hepburn replies, with irony which becomes obvious, “You people in the provinces must stop thinking in this way. How do you know what a gunman looks like these days?” Cushing is also perfect: much more harsh and unlikable than as Van Helsing or even Baron Frankenstein. Indeed, if there’s a character in his Hammer filmography that’s most similar, it may be the Puritan witch-hunter, Gustav Weil, from Twins of Evil.

Both leads, who had partnered up previously as Holmes and Watson in The Hound of the Baskervilles, are excellent. Gore-Hepburn is exactly the sort of charismatic character you can see pulling this off. I was reminded of classic Fawlty Towers episode, “A Touch of Class”, in which Basil falls victim to the fake Lord Melbury, who couldn’t possibly be a conman. Here, Pearson tells the robber, “If I may say so, sir, you don’t look much like a gunman,” to which Gore-Hepburn replies, with irony which becomes obvious, “You people in the provinces must stop thinking in this way. How do you know what a gunman looks like these days?” Cushing is also perfect: much more harsh and unlikable than as Van Helsing or even Baron Frankenstein. Indeed, if there’s a character in his Hammer filmography that’s most similar, it may be the Puritan witch-hunter, Gustav Weil, from Twins of Evil.

It is certainly a time-capsule, from an era with a much firmer system of class and structure in place, when your boss was your boss, rather than your pal. Hell, even the setting is something of a bygone era – I can’t remember the last time I was inside an actual, physical bank. But the concept at its core hasn’t dated at all, and it’s a solid small-scale thriller, depicting the dismantling of a man who believes his life to be one of perfect order.

This review is part of Hammer Time, our series covering Hammer Films from 1955-1979.