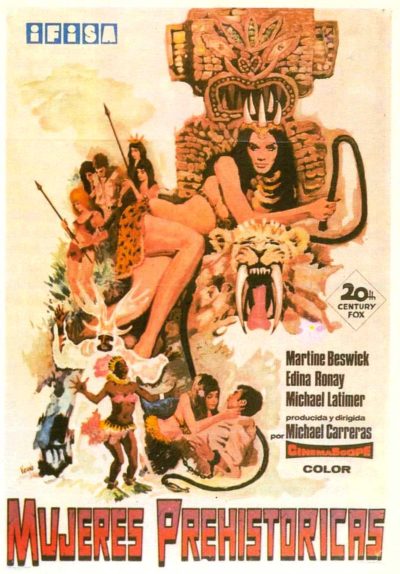

Rating: D

Dir: Michael Carreras

Star: Michael Latimer, Martine Beswick, Edina Ronay, Stephanie Randall

a.k.a. Prehistoric Women

If there’s anything I’ve learned from watching Hammer films, it’s that when the locals deliver an ominous warning, you should probably listen. That might be an innkeeper suggesting you avoid the castle looming over the village. Perhaps a Bedouin recommendation to take your archeological dig away from the Pharaoh’s tomb. Or, in this case, your native jungle guide saying, “Here, the devils of darkness are all about us! The spirits of the past that protect the forest lands from the desecration of unworthy eyes.” Yeah, that’s a bit of a red flag. Probably best to head back to camp at this point.

But David Marchand (Latimer) is made of sterner stuff. He’s there, trying to track down a wounded leopard, injured by the big-game hunter he was accompanying. This job seems just a bit at odds with his earlier statement: “The animals in this country are part of my life, and I hate to see them abused in any way.” O RLY? Like – I dunno – helping someone shoot them for sport? So it’s kinda hard for me to feel much sympathy when he ignores the warning he is given, and goes into territory belonging to the Kunaka tribe, who worship a giant white rhino statue. Not three minutes after asking, “The devils of what?”, he has been captured by them, and soon after, is standing in front of the statue, about to be executed for his trespass.

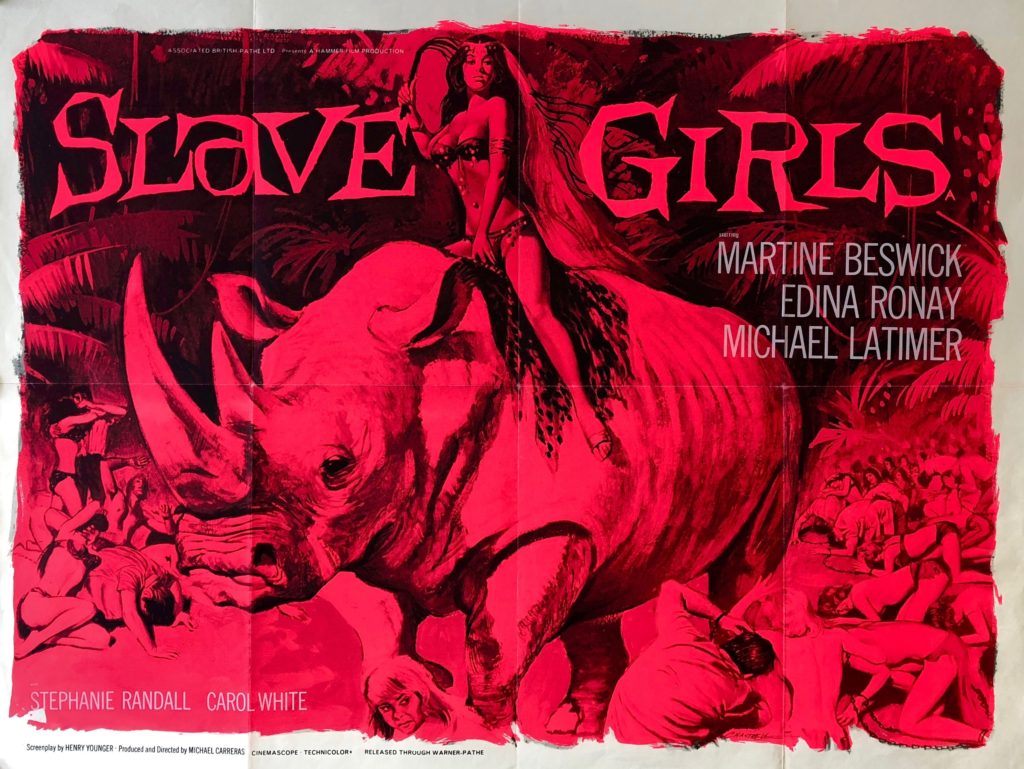

This is when things get weird. For the world around David freezes, leaving him to saunter through a sudden crack in the wall. What happened? I’ve no clue. No explanation is ever provided. It seems to be some kind of a time-warp, taking him back to an era when the same statue was being worshipped – just a cleaner, fresher version. He quickly discovers this world is ruled by the cruel Queen Kari (Beswick), with her kingdom divided into three groups. She and her dark-haired female court are the ruling class. They lord it over Saria (Ronay) and the blonde girls, who are kept very much under the thumb of Kari. Regularly, blondes are offered as a bride to the white rhino, shown top. I’m not going to get into the phallic symbolism there, but I’ll confess to making a few “Do I make you horny?” comments, in my best Austin Powers voice.

This is when things get weird. For the world around David freezes, leaving him to saunter through a sudden crack in the wall. What happened? I’ve no clue. No explanation is ever provided. It seems to be some kind of a time-warp, taking him back to an era when the same statue was being worshipped – just a cleaner, fresher version. He quickly discovers this world is ruled by the cruel Queen Kari (Beswick), with her kingdom divided into three groups. She and her dark-haired female court are the ruling class. They lord it over Saria (Ronay) and the blonde girls, who are kept very much under the thumb of Kari. Regularly, blondes are offered as a bride to the white rhino, shown top. I’m not going to get into the phallic symbolism there, but I’ll confess to making a few “Do I make you horny?” comments, in my best Austin Powers voice.

Meanwhile, the men – regardless of hair colour – are kept locked up and in darkness. David quickly ends up enjoying the same accommodations, spurning Kari’s advances after seeing her cruelty in full effect. While imprisoned there, he learns a bit about the history of the place. But don’t worry: this will not be on the end of term test, and it provides a good opportunity to go get a snack. However, he begins to plot, working on aligning the men with the blondes, in a revolution against Kari and her rhino-masked enforcers. This eventually ends in the expected battle, and what can only be described as a rhino ex machina. I won’t spoil it, but let’s just say, I’m sure Kari… gets the point.

As David and Saria are about to get together, he suddenly finds himself back where he was. Which, in case you’d forgotten, is where David was about to be executed. Naturally, that’s avoided and he goes back to camp – and one final surprise awaits, in the form of a new arrival. It’s legendary British actor, Steven Berkoff, in his first credited role! No, seriously! But I imagine it’s another new arrival by which the makers intend us to be surprised. Though the twist might have had more impact, if it hadn’t been telegraphed to the point that Chris saw it coming, well in advance.

I think it is probably duelling with The Viking Queen for the title of worst Hammer film to this point in their chronology. It probably wins, as at least Queen offered some camp value. This is mostly painfully dull, with only Beswick apparently trying very hard. It doesn’t help that the blondes costumes are obviously recycled, virtually without modification, from One Million Years B.C. (perhaps explaining the title change in the US), while the plot feels more or less copied wholesale from She. But here, you get two White Saviour instances for the price of one, Marchand being the catalyst for change in both real and Kari’s world. Though at least the black people here are not portrayed by Michael Ripper under a tin of shoe-polish, even if little acting is required from them.

Any sense of the exotic is severely undermined by the copious presence of obvious British accents. I mean, the first member of the Kunaka tiribe David encounters appears to have gone to Eton, setting a pattern for what is to come. The mere fact he speaks English at all should have been worthy of comment. That he sounds as if he has just come off a shift on the news desk at the BBC World Service is, frankly, embarrassingly lame, and the blondes consequently resemble a fancy-dress party for Sloane Rangers. Something similar can be said for most other aspects, probably peaking with the climactic white rhino, which is very obviously a stuffed creature being moved about on roller-skates. Compared to She or Years, there is no sense of spectacle at all, and you don’t even have the presence of Peter Cushing or Ray Harryhausen’s stop-motion animation to enjoy.

Latimer is expected to be the focus for the audience, and just isn’t up to the job; it’s easy to see why this was close to his only leading role, along with Pete Walker’s gangster cheapie, Man of Violence. While Beswick does her best, having earned promotion after her work in Years, she can’t overcome all the thoroughly underwhelming other aspects. If the films had been made today, this would have felt like a “mockbuster” version of She, churned out by an opportunistic studio like The Asylum. And not even one of their half-decent efforts, like War of the Worlds.

This review is part of Hammer Time, our series covering Hammer Films from 1955-1979.