Rating: D+

Dir: Michael Powell

Star: Carl Boehm, Anna Massey, Maxine Audley, Moira Shearer

I’m not sure many films have undergone such a critical 180 since their release. Initially, this was absolutely torched. The Tribune’s Derek Hill was about in line with the general opinion when he wrote, “The only really satisfactory way to dispose of Peeping Tom would be to shovel it up and flush it swiftly down the nearest sewer. Even then, the stench would remain.” It effectively ended Powell’s career as a major film-maker. Now? 96% fresh on Rotten Tomatoes, and among the ten best horror films of all time. Well, according to The Guardian, anyway. But as the grade above suggests, this is Jim not agreeing with something in The Guardian. Shocking, I know.

Not that I agree much with the earlier critics either, such as The Observer’s Catherine Lejeune, who said “It’s a long time since a film disgusted me as much.” Much like the early Hammer films, society has moved on, and the content here is no longer more than lightly disturbing. Unlike the early Hammer films, however, the rest of the film – such as the performances or production quality – don’t compensate for the lack of shock value. Yes, I get that it’s all about voyeurism, implicating the audience by implication in the killer’s violent acts. Lord, do I get it, for the movie hammers this home with painful earnestness. Look! The killer works in a film studio! This kind of self-referential navel-gazing is lapped up by critics. But I think Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer made the same point just as effectively, and considerably more efficiently, in its notorious “home video” sequence.

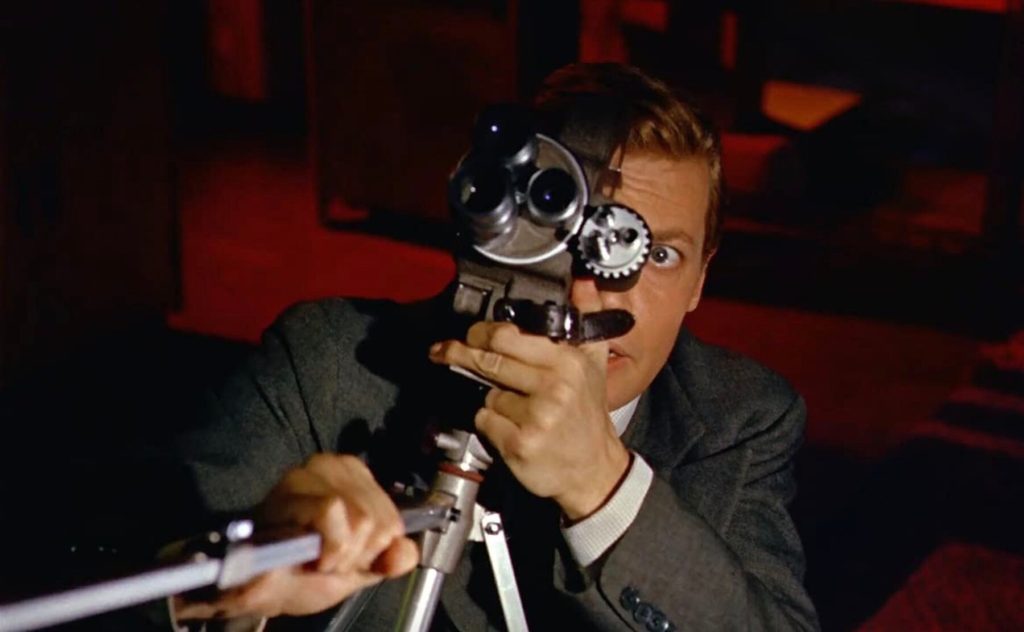

What Peeping Tom does, that was somewhat unprecedented for the time, is focus almost entirely on the killer, Mark Lewis (Boehm). He went through mental hell as a child, due to the experiments in fear carried out on him by his psychologist researcher father (played by the film’s director, whose actual son portrays the young Mark Lewis). As a result, he is obsessed with both fear and filming. He has become a cinematic serial killer, who records women as he menaces and stabs them dead with a blade concealed in the leg of his hand-held camera’s tripod. There’s also a mirror attached, so his victims can see themselves dying. I will admit, that is fairly twisted, and I can see why the kinder, gentler critics of the time came down with a case of the vapours.

What Peeping Tom does, that was somewhat unprecedented for the time, is focus almost entirely on the killer, Mark Lewis (Boehm). He went through mental hell as a child, due to the experiments in fear carried out on him by his psychologist researcher father (played by the film’s director, whose actual son portrays the young Mark Lewis). As a result, he is obsessed with both fear and filming. He has become a cinematic serial killer, who records women as he menaces and stabs them dead with a blade concealed in the leg of his hand-held camera’s tripod. There’s also a mirror attached, so his victims can see themselves dying. I will admit, that is fairly twisted, and I can see why the kinder, gentler critics of the time came down with a case of the vapours.

He lives in part of the family house, and rents out rooms to tenants, such as Helen Stephens (Massey) and her blind mother (Audley). Helen basically forces her way into his flat, and learns of Mark’s background. Instead of nopeing the fuck out of there, considering the man is a walking red flag, she begins a relationship with him. Meanwhile, Mark is continuing to kill, his victims including a stand-in at the studio, and a model for his sideline business of nudie pictures, sold by a local newsagent [Kids! Ask your parents! Probably about what a “newsagent” is, as well as about “nudie pictures”]. Mrs. Stephens – every bit as much a busybody as her daughter, it seems – isn’t quite as convinced of Mark’s charms.

My first problem is Boehm, and his inexplicable, quite strong German accent. Mark even says he’s lived in the same English house all his life, so why does he sound like a Nazi officer from The Guns of Navarone? It’s an unnecessary distraction: dammit, if they wanted a creepy German landlord, they should have hired Klaus Kinski, who showed what he could do with that role in Crawlspace. In comparison, Boehm is severely lacking in intensity, and I did not find his portrayal convincing. Indeed, few of the performances were – save perhaps Pamela Green the glamour model, playing Milly the glamour model. She provides the film’s sole glimpse of stocking (top), to quote Cole Porter. Blink and you’ll miss it.

In acting terms, this probably reaches the bottom, when Mark comes home to find Mrs. Stephens in his room. The consequent scene is a battle of overwrought acting, which left me yearning for the subtlety of Anthony Perkins. For a few months later, Psycho would get a UK release, and demonstrate how the concept of everyday menace and parental damage should be done. The scripting here is pretty lazy too: on the way to kill his first victim, her landlady (or madam) obviously sees Mark’s face. But the authorities are apparently entirely clueless, almost farcically incompetent, until a passing psychiatrist who was pals with Lewis Sr. pops by the studio.

Which reminds me: the scene where he kills the stand-in there (Shearer) is just way too long. I guess it’s an attempt to build tension, with the audience knowing the threat Mark poses. Yet it instead feels like she’s going to interpretively dance him into unconsciousness and escape. As with all the other murders, the film makes its excuses here and leaves, before the act is completed. Can’t really blame Powell for this: we were still three years before Blood Feast would open the doors to the graphic violence we now know. But, again, there’s a reason you just need to say “shower scene” and everyone knows what you mean.

Which reminds me: the scene where he kills the stand-in there (Shearer) is just way too long. I guess it’s an attempt to build tension, with the audience knowing the threat Mark poses. Yet it instead feels like she’s going to interpretively dance him into unconsciousness and escape. As with all the other murders, the film makes its excuses here and leaves, before the act is completed. Can’t really blame Powell for this: we were still three years before Blood Feast would open the doors to the graphic violence we now know. But, again, there’s a reason you just need to say “shower scene” and everyone knows what you mean.

Heresy though it may be to say it, I wonder if this might be ripe for a remake? We already had one entry in this series, The Fly, where a modern film-maker was able to see the potential in a “classic”, AND spin it in new ways. This feels like the same could be possible, perhaps reflecting a world where everyone carries a high-resolution movie camera in their pocket, and there’s no need for film, developing or projectors. Voyeurism is no longer a fetish in modern society – it’s everyday life, between reality TV, TikTok and Twitter. However, given the high esteem in which this is held (rather inexplicably, as far as I’m concerned), it would be a brave director who would take it on.

This article is part of our October 2022 feature, 31 Days of Classic Horror.