Rating; C+

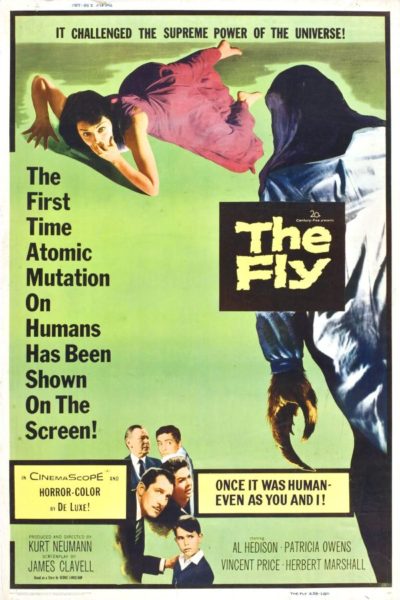

Dir: Kurt Neumann

Star: Patricia Owens, David Hedison, Vincent Price, Herbert Marshall

Another one I haven’t seen in a long time, to the point I was quite surprised it was in colour. The other element which was unexpected, was its focus on a female character, Helene Delambre (Owens). Really, how many horror/SF films in the fifties did that? I think if you polled the general public, many people would tell you Vincent Price is the star, and perhaps also plays the teleportation inventing scientist. Neither is the case. He’s about third banana, playing Francois Delambre, the brother and business partner of said scientist, Andre (Hedison). Francois gets a late-night call from Helene, confessing to having killed her husband. In a hydraulic press. Which has to be one of the more gnarly deaths available.

She happily repeats the story to investigating officer, Inspector Charas (Marshall), but refuses to explain why she did it. Charas isn’t sure whether she was just insane, but there are weirdnesses that Francois can’t shake. Firstly, the way Andre’s laboratory is destroyed. Then there’s Helene’s new-found obsession with flies in general, and one in particular, sporting a white head. After pretending to have caught said insect, Francois gets his sister-in-law to ‘fess up about what happened, and the bulk of the story unfolds in flashback. Andre had come up with a teleportation device, but while testing it on himself, failed to notice a fly in the apparatus, and its DNA was mixed with his. This led to him becoming half-man, half-fly and the resulting, relentless degenerative process is what eventually led to his… uh, “press” conference.

The script for this was the first produced screenplay by James Clavell, better known as an author of door-stop novels like the 1,150-page Shogun. But he actually had a fairly notable career in the movie business. He also wrote the script for The Great Escape, and directed To Sir, With Love. The director here, Kurt Neumann, was German-born but had worked in Hollywood since the thirties. Prior to this, he was likely best known for Rocketship X-M, starring Lloyd Bridges, an early “mockbuster” designed to steal thunder of George Pal’s Destination Moon. Hedison – billed here as “Al”, though he’d subsequently switch to David – would star in Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea, and also play Felix Leiter in Live and Let Die and Licence to Kill.

The script for this was the first produced screenplay by James Clavell, better known as an author of door-stop novels like the 1,150-page Shogun. But he actually had a fairly notable career in the movie business. He also wrote the script for The Great Escape, and directed To Sir, With Love. The director here, Kurt Neumann, was German-born but had worked in Hollywood since the thirties. Prior to this, he was likely best known for Rocketship X-M, starring Lloyd Bridges, an early “mockbuster” designed to steal thunder of George Pal’s Destination Moon. Hedison – billed here as “Al”, though he’d subsequently switch to David – would star in Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea, and also play Felix Leiter in Live and Let Die and Licence to Kill.

As someone who is a fan of David Cronenberg’s version, watching this was a bit of an odd experience. It’s not bad, but falls short in some areas. Perhaps most obviously, the remake’s pacing is far better, depicting the slow transformation of Brundle into Brundlefly. Here, he gets the head and the arm of a fly, right from the get-go, and there’s no physical change thereafter. Everything else is mental and internal, which makes for generally far less disturbing cinema: though his inabilty to disable CAPS LOCK on his typewriter offended my literary sense. In fairness, the restraint is a result of its time, when special effects were more primitive, and censorship considerably more strict. Still, like the films Hammer was making, it didn’t stop critics lobbing bombs, in this case such as, “one of the most revolting science-horror films ever perpetrated.”

Not that it doesn’t have its moments. Of course, everyone remembers the ending, with the fly-human stuck in the spider’s web, and its high-pitched shrieking, “Help me! Help me!” That was something which had lingered from the last time I saw it, and still packs a punch. But there are a couple of other things that stick in my mind. Soon after his transformation, Andre requests a bowl of milk with rum from Helen, which he drinks while concealing his actions with the cloak draped over his head. The resulting sucking sounds are somehow horrific, in a way that almost matches Brundlefly’s dinner habits in the remake.

There’s also the scene in which Andre is crushed. While hardly gory – it really needs significantly more gobbets of flesh, and a far crunchier soundtrack – the way in which Helene tucks in her late husband’s fly-arm and releases the press again, is surprisingly chilling, especially in the pre-feminist era. It is a little odd, considering Helene has proven to be a bit of a screamer, to put it mildly: witness her response to seeing both that fly-arm and, later, the fly-head. It’s possible the latter simply “broke” Helene, and everything there after is unfolding, as far as she’s concerned, in a waking nightmare. Her subsequent refusal to explain her motives seems cut from a similar, emotionally dead cloth.

However, there are weaknesses. As well as the previously-mentioned pacing, there is way too much fly-catching going on here, a sport which I can only conclude, must be better as an active participant than a spectator. Mind you, Montreal seems entirely fly-infested, in a way I’m not used to in my current desert climate. If I see more than one fly in a week here, it’s a matter of note. [The location was changed from Paris in George Langelaan’s short story in the June 1957 issue of Playboy. I guess someone did read it for the articles…] There’s also a weird angle where Francois confesses to having loved Helene, but stepped aside so his brother could marry her. The very ending perhaps implies she may be going for the bare minimum in terms of mourning, and feels quite jarring.

However, there are weaknesses. As well as the previously-mentioned pacing, there is way too much fly-catching going on here, a sport which I can only conclude, must be better as an active participant than a spectator. Mind you, Montreal seems entirely fly-infested, in a way I’m not used to in my current desert climate. If I see more than one fly in a week here, it’s a matter of note. [The location was changed from Paris in George Langelaan’s short story in the June 1957 issue of Playboy. I guess someone did read it for the articles…] There’s also a weird angle where Francois confesses to having loved Helene, but stepped aside so his brother could marry her. The very ending perhaps implies she may be going for the bare minimum in terms of mourning, and feels quite jarring.

The machinery on view has not stood the test of time, except perhaps as an illustration of what pre-transistor computing technology looked like. What are the purpose of the neon light tubes? Neumann shoots the teleportations in particularly rote fashion: it feels he uses the same shots in the same order, every time. Drink every time you see the gauge! I suspect if it wasn’t for Price, this might have been forgotten considerably more, and left to lie alongside the slew of other fifties entries, in which mankind meddles in things they shouldn’t. I think it’s safe to say this is one of the cases where the remake is superior to the original.

This article is part of our October 2022 feature, 31 Days of Classic Horror.