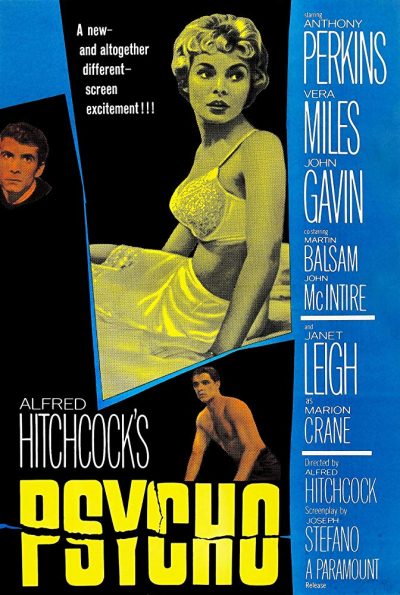

Rating: B

Dir: Alfred Hitchcock

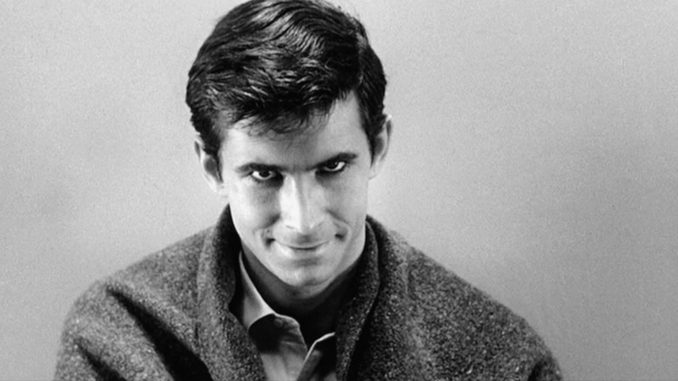

Star: Anthony Perkins, John Gavin, Vera Miles, Janet Leigh

“Blondes make the best victims. They’re like virgin snow that shows up the bloody footprints.”

— Alfred Hitchcock

Is it possible for a film to be too iconic? That may be the case for Psycho. Watching it now, it’s hard to understand why Marion Crane (Leigh) doesn’t make an excuse and leave, at high speed, the motel owned by the creepily charming Norman Bates (Perkins). For there are red flags all over the place. Norman’s hobby of taxidermy. Sudden fits of rage. His devotion to his mother, shown in lines like “A boy’s best friend is his mother.” All of which should set off alarm bells in any normal person these days. Except, you then realize, most of these weren’t red flags until Hitchcock made them so here. He is the reason why, whenever anyone in a film looks for a weapon in a kitchen, 99% of the time they will pick up “that” knife.

However, is it Psycho‘s fault the language it spoke at the beginning of the sixties, has become the stuff of cliche in the 21st century? Arguably not. Something for which it can’t escape blame though, is the way it becomes considerably less interesting when Norman – and, to a lesser extent, Marion – are not in the screen. Much of the second half is instead taken up with the Scooby-like efforts of her boyfriend Sam Loomis (Gavin) and sister Lila (Miles) to track down the missing Marion. The former is blandly macho, the latter about as useless as most women were in movies of the era – while the film was ahead of its time in some areas, gender equality clearly wasn’t one of them. Perhaps that is why Hitchcock felt the audience needed a lecture at the end on why Norman is “not exactly” a transvestite.

However, is it Psycho‘s fault the language it spoke at the beginning of the sixties, has become the stuff of cliche in the 21st century? Arguably not. Something for which it can’t escape blame though, is the way it becomes considerably less interesting when Norman – and, to a lesser extent, Marion – are not in the screen. Much of the second half is instead taken up with the Scooby-like efforts of her boyfriend Sam Loomis (Gavin) and sister Lila (Miles) to track down the missing Marion. The former is blandly macho, the latter about as useless as most women were in movies of the era – while the film was ahead of its time in some areas, gender equality clearly wasn’t one of them. Perhaps that is why Hitchcock felt the audience needed a lecture at the end on why Norman is “not exactly” a transvestite.

Yet it’s certainly not without brilliance. The shower scene has, rightly, taken its place, perhaps the single most iconic moment in horror history, though is another aspect which has been done to death over the six decades since. Yet worth noting almost as much, is what precedes and follows it: Norman spying on Marion, and then methodically cleaning up after “Mother” has done the dirty deed. For all told, it’s about sixteen and a half minutes without any meaningful dialogue (beyond Norman yelling, “Mother! Oh god, Mother! Blood!”), and remains remarkable, even today. Alfred Hitchcock cares not for your cinematic conventions. The fate of PI Milton Arbogast is also striking: check out the camera shots both as he climbs and descends the stairs.

It makes for a weird grab-bag of the painfully over-familiar and the still impressive, with Perkins’s performance certainly in the latter category. Worth noting, he wasn’t unknown at the time: he was already an Oscar-winner, having taken home the Academy Award as Best Supporting Actor for his performance in 1957’s Civil War drama, Friendly Persuasion. But for good or bad, Norman Bates defined Anthony Perkins, and for almost the rest of his career, he was still playing the psycho, whether in Edge of Sanity or Crimes of Passion. I guess, if you’re really good at something, why stop doing it?

This article is part of 31 Days of Horror.

[August 201o] It’s fifty years since Psycho came out, and it is still regarded as one of the classics of the horror genre. If ever the phrase “no recap needed” was true, this is it, for I doubt anyone reading this site is unaware of the plot. It resonates to such an extent that whenever anyone in a horror film picks up a kitchen utensil, it will almost inevitably be “the Psycho knife.” However, from a modern point of view, it isn’t obviously a genre entry: and even at the time, there was almost as much fuss over a shot of a toilet being flushed, or the script using the word “transvestite”, as the killing of Marion Crane (Leigh) in the shower.

It’s almost a noir, not just in style but content, with Crane going on the lam with $40,000, and being followed by a private-eye and her sister, who think her boyfriend (Gavin, who was almost James Bond after George Lazenby) knows about her disappearance. Even the lengthy psychological explanation at the end is not exactly the sort of thing found in most slasher pics since. I wouldn’t describe it as a great horror film; one wonders why moviegoers in the 60’s were even startled by Leigh’s death, given the opening credits say “and Janet Leigh” – a position we know as reserved for the big-name star wheeled into horror flicks for a quick death e.g. Udo Kier in FeardotCom.

However, qualms about genre categories aside, it still works very well, with Perkins in a career-defining role, literally; it was hard to see him in any other kind of role after this, though he never seemed to mind being typecast. Even if it now possesses as much terror value as a pair of your favourite socks, and about the same shock content, there’s no denying the art and craft on view, and it’s easy to see why Hitchcock is a master, and this is one of his most well-regarded works. Even considered, on its most basic level, as a cinematic machine for generating suspense and tension, it hasn’t been matched very often in the five decades since its original release. B