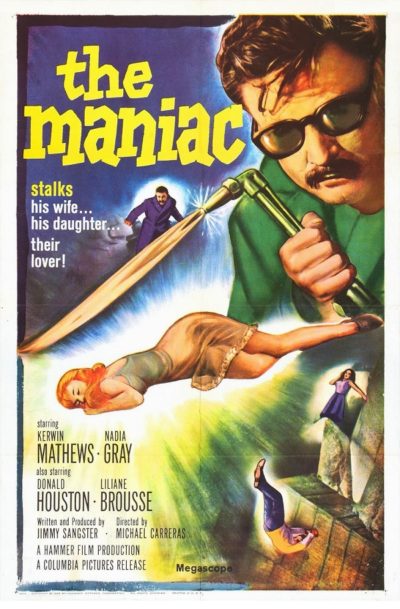

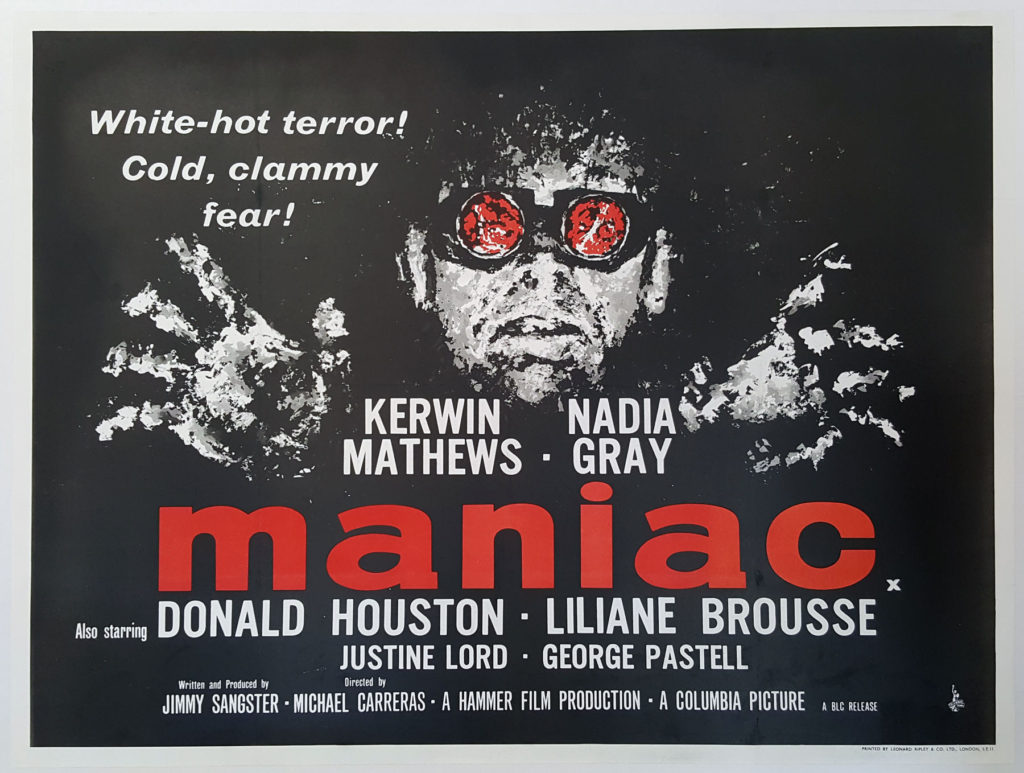

Rating: C-

Dir: Michael Carreras

Star: Kerwin Mathews, Nadia Gray, Liliane Brousse, Donald Houston

a.k.a. Maniac

What was it about Hammer setting films in the South of France? Did Sir James Carreras have a summer-house on the Cote D’Azur or something? This would be the fourth such in five years, after The Snorkel, The Full Treatment and Paranoiac. There’s a whole continent not within an easy commute of the Promenade des Anglais in Nice, y’know. This one does, at least, move somewhat away from the obvious tourist-traps, relocating to the Camargue region, between the two arms of the Rhone where it enters the sea. An opening title helpfully informs us this is “a remote area in Southern France where wild horses roam, fighting bulls are bred and violence is never far away”. Only one of these three elements plays any significant in proceedings, and no prizes for guessing which.

Not to be confused with Maniac – either Dwain Esper’s thirties horror, William Lustig’s eighties grindhouse slasher, or Franck Khalfoun remake of the latter from 2012 – this is another of Jimmy Sangster’s psychological thrillers, though considerably less plausible than some. American “painter”, with quotes used advisedly, since we never see him pick up a brush, Jeff Farrell (Mathews) has a spat with his girlfriend, after which she zips off in her car, leaving him stranded in a small French village. Still, he’s not unhappy, setting up shop in the local inn, where both owner Eve Beynat (Gray) and her teenage daughter, Annette (Brousse), are soon making gooey eyes at the handsome visitor. But there’s a motive at work beyond lust, at least in Eve’s case.

For her husband, Henri (Houston), is currently locked up in an insane asylum, after an incident four years previously. Annette, then fifteen, was assaulted by a local man, who was captured by Henri and introduced to the business end of an acetylene torch. Eve wants to break him out, and needs a patsy to help in the task. But, of course, it’s never that simple, is it? It’s not long before a dead body has turned up in the trunk of the getaway car, and Jeff’s dreams of a holiday worthy of a letter to Penthouse Forum about his mother-daughter experience, has turned into something closer to a nightmare. He should probably have guessed that getting the husband of the woman you’re banging out of the loony bin, where he has been incarcerated for blowtorch assault, has a number of obvious potential disadvantages. It’s not like the madman is going to say, “Thanks for the help – here, have my wife and daughter.”

For her husband, Henri (Houston), is currently locked up in an insane asylum, after an incident four years previously. Annette, then fifteen, was assaulted by a local man, who was captured by Henri and introduced to the business end of an acetylene torch. Eve wants to break him out, and needs a patsy to help in the task. But, of course, it’s never that simple, is it? It’s not long before a dead body has turned up in the trunk of the getaway car, and Jeff’s dreams of a holiday worthy of a letter to Penthouse Forum about his mother-daughter experience, has turned into something closer to a nightmare. He should probably have guessed that getting the husband of the woman you’re banging out of the loony bin, where he has been incarcerated for blowtorch assault, has a number of obvious potential disadvantages. It’s not like the madman is going to say, “Thanks for the help – here, have my wife and daughter.”

Sangster seeks to make up for the quality of the twists by increasing the quantity, especially towards the end, where they get piled on an almost absurd rate. This is the kind of film which is obviously setting things up for dramatic revelations, to the extent that we were seeing them coming, even where none existed. For example, I was certain that Inspector Etienne, the official investigating Henri’s escape from the asylum, was going to be involved somehow. However, turns out he is simply the police officer he appears to be. Which probably makes him unique among the characters in this, save perhaps for Annette. Though she seems there simply to be eye-candy: the plot would largely function well enough without her EuroTottiness, pleasant though it is.

She does serve a purpose at the end, being hunted round a very spectacular quarry in Les Baux (the French mining town which gave its name to bauxite, fact fans), in what is an admittedly impressive climax. This does make good use of the local landscapes, and that is an area in which the film does well. At the other end of the spectrum, is probably the scene where Jeff is hanging out in the hotel bar, and starts “dancing” with Annette (she’s supposed to be working, but never mind). Quotes again used advisedly, as this GIF will illustrate. I guess entertainment is hard to come by in the Camargue. For, inexplicably, the entire bar watches this performance with rapt attention, and bursts into spontaneous applause at the end. Well, save for Eve, anyway, whose gaze could cut glass. Everyone’s a damn critic.

It’s another of Hammer’s psycho-thrillers shot in black-and-white. I don’t know what percentage of movies by 1963 were filmed this way, but imagine it was likely a small minority. I did find one article stating, “By the late 1950s, most Hollywood productions were being shot in color.” I suspect the choice here was largely a result of Hitchcock’s decision to shoot Psycho in monochrome, though even he had been shooting in Technicolor for more than a decade, since Rope in 1948. While there are times when the content fits the style, this doesn’t seem like one of them. A lushly coloured version might have been better suited to depicting what is, after all, largely a series of crimes passionnel, carried out in the summer heat of southern France. Sepia tinting feels more appropriate than stark and chilly monochrome.

It’s another of Hammer’s psycho-thrillers shot in black-and-white. I don’t know what percentage of movies by 1963 were filmed this way, but imagine it was likely a small minority. I did find one article stating, “By the late 1950s, most Hollywood productions were being shot in color.” I suspect the choice here was largely a result of Hitchcock’s decision to shoot Psycho in monochrome, though even he had been shooting in Technicolor for more than a decade, since Rope in 1948. While there are times when the content fits the style, this doesn’t seem like one of them. A lushly coloured version might have been better suited to depicting what is, after all, largely a series of crimes passionnel, carried out in the summer heat of southern France. Sepia tinting feels more appropriate than stark and chilly monochrome.

There’s not much special about the performances here, though I did like Nadia, who manages to switch between protective mother and needy sex-pot quite effectively. Mathews had made little impression in The Pirates of Blood River – I think I used the words “sheer blandness”, and he is equally forgettable here. Jeff describes himself, almost proudly, as a misogynist, yet there’s precious little to suggest that’s the case. It’s a character that is in desperate need of more edge than Mathews is able to provide. I can’t help thinking that Oliver Reed, then a studio player, would have been a better fit for the role. As Henri, I’m not sure which is less convincing: Houston’s moustache, or the Welsh actor’s attempt at a French accent. He is rather more menacing and effective, when letting his blow-torch do the talking for him. As a one-off watch, this passes muster, yet now I know its twists and turns, I doubt it’s one I’ll ever watch again.

This review is part of Hammer Time, our series covering Hammer Films from 1955-1979.