Rating: C

Dir: Tony Mitchell

Star: Robert Carlyle, Jessalyn Gilsig, Tom Courtenay, Joanne Whalley

The disaster movie is often though of as a Hollywood phenomenon. But it can be argued that it’s a genre with its roots in Britain. For what is H.G. Wells’s War of the Worlds, if not disaster porn? And it has been suggested that the first such film was Fire!, a 1901 silent short, directed by James Williamson and filmed in that forerunner of Pinewood and Elstree: Hove. The British Film Institute calls it, “One of the most important milestones in the development of film language.” It is certainly true that it is a field which has been wholeheartedly embraced by the American film industry. While the United Kingdom may get a passing mention – typically with Tower Bridge or Buckingham Palace being destroyed – disaster movies made and set entirely on this sceptred isle have been few and far between. Threads, 28 Days Later and London Has Fallen are probably the best-known.

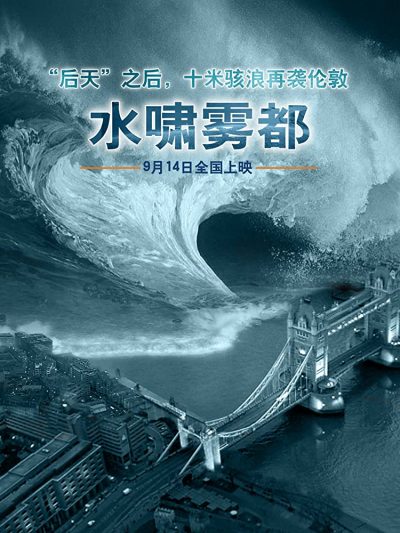

In comparison to those, Flood largely came and went without much attention, despite a reasonable budget of $24 million. Perhaps this was because it occupied an odd middle-ground between “proper” feature and TV mini-series. It originally received a theatrical release in a 110-minute version, but only in one British cinema – it got a far bigger release in Russia and China. The following year, it was broadcast on UK television with 77 more minutes, which makes me wonder if that was the aim all along. It certainly ticks all the boxes familiar from previous entries, from a scientist no-one believes through to heroic self-sacrifice as music swells. Though naturally, the disaster in question is a quintessentially British one: the weather. I’m just disappointed no-one looked up at the sky and said, “Think it might be easing up,” or tried to have a barbecue.

It does at least start in unfamiliar territory. There is a roll of dishonour, the great cities of the world which have been victimized in this kind of film. Washington D.C. in Independence Day. Las Vegas in Mars Attacks! Tokyo in… most of Toho Studio’s output since 1954. To that list can now be added the name of Wick, Caithness. This municipality is located almost at the very tip of Scotland, and Wikipedia tells me it is home to the world’s shortest street, Ebenezer Place, measuring 2.06 metres in length. Why writers Justin Bodle, Matthew Cope and Nick Morley chose it for the first place to feel the meteorological wrath in the films is unclear. Maybe one of them had a bad experience at the local chippie. Or perhaps, as in The Night That Panicked America, they lobbed a dart at a map and picked their location that way.

It does at least start in unfamiliar territory. There is a roll of dishonour, the great cities of the world which have been victimized in this kind of film. Washington D.C. in Independence Day. Las Vegas in Mars Attacks! Tokyo in… most of Toho Studio’s output since 1954. To that list can now be added the name of Wick, Caithness. This municipality is located almost at the very tip of Scotland, and Wikipedia tells me it is home to the world’s shortest street, Ebenezer Place, measuring 2.06 metres in length. Why writers Justin Bodle, Matthew Cope and Nick Morley chose it for the first place to feel the meteorological wrath in the films is unclear. Maybe one of them had a bad experience at the local chippie. Or perhaps, as in The Night That Panicked America, they lobbed a dart at a map and picked their location that way.

Whatever the reason, Wick gets blasted by a storm surge, setting the tone for the effects over the next three hours. The sequences which feature real water, e.g. surging into houses and washing locals away, are quite effective. The CGI is not. This is just an appetizer, of course: how much devastation can a town of population 7,333 (per the 2001 census) offer? Like all bad things e.g. country/western music, the storm comes from America, but makes a right turn after Wick, pausing only to wipe out Arbroath, then lurks menacingly off-shore for a bit. This allows Met Office spokesman Keith Hopkins (Nigel Planer, looking as hangdog as Neil ever did in The Young Ones) to say things like “Based on the available data, the storm is moving northeast back into the North Sea.” Naturally, this proves as accurate as Michael Fish’s infamous “A woman rang the BBC and said she heard there was a hurricane on the way” forecast.

As mentioned, there is the inevitable Scientist Who Won’t Be Listened To. This is Prof. Leonard Morrison, played by Courtenay, who has been saying for decades that the Thames Barrier, intended to protect London from exactly this kind of surge, was built in the wrong place. The confluence of a “thousand-year storm” and the “highest tide of the year” are going to prove him right, though not until there’s only a couple of hours until the water reaches Central London. Meanwhile, he completes the usual disaster movie character exacta, by also having a son from who he is currently estranged. This is engineer Rob Morrison (Carlyle), who gets called in to do some work at the Barrier where – really, what are the odds? – his ex-wife Samantha Morrison (Gilsig) oversees things. Cue the expected awkward banter, intended to establish that they still have feelings for each other, which will blossom through the shared, extremely moist adversity sure to come.

While much of the film was shot in South Africa, there was clearly location shooting done in London. I do wonder how they wangled permission to film at the real Thames Barrier, considering the theme of the film is basically that the Barrier proves as useful as a chocolate teapot. Can you imagine, say, the makers of Chernobyl calling up the Ukrainian government, and asking, “Can we shoot in one of your old nuclear plants – the more dilapidated the better. We’ll give you a screen credit.” Things largely unroll as expected, with the water rushing up the Thames, over the top of the Chocolate Teapot, and on into London. The Morrison clan get washed off the barrier, but miraculously end up in the depths of Charing Cross station, from where they have to escape. Alongside them are characters played by less familiar names than Carlyle, which immediately slashes their survival chances.

While much of the film was shot in South Africa, there was clearly location shooting done in London. I do wonder how they wangled permission to film at the real Thames Barrier, considering the theme of the film is basically that the Barrier proves as useful as a chocolate teapot. Can you imagine, say, the makers of Chernobyl calling up the Ukrainian government, and asking, “Can we shoot in one of your old nuclear plants – the more dilapidated the better. We’ll give you a screen credit.” Things largely unroll as expected, with the water rushing up the Thames, over the top of the Chocolate Teapot, and on into London. The Morrison clan get washed off the barrier, but miraculously end up in the depths of Charing Cross station, from where they have to escape. Alongside them are characters played by less familiar names than Carlyle, which immediately slashes their survival chances.

And like most entries, the cast is full of names and faces you’ll recognise. Probably the most surprising is future Oscar nominee Tom Hardy, here in the supporting role of a lowly London Underground employee. He seems to spend most of the film getting sloshed around tube tunnels. As well as those noted previously, David Suchet plays the deputy Prime Minister, who has risen to the level of his own incompetence, and we kinda disturbed to see Pip Torrens, a.k.a. Herr Starr from Preacher, as an army liaison officer. Of all the names, it’s probably Joanne Whalley who comes off best, playing Metropolitan police commissioner Patricia Nash. Her character demonstrates an admirable kind of clear-headed thinking which is necessary in a crisis, especially one like this which requires hard choices to be made.

All told, I’d probably rather have seen more of this aspect, and less of the Morrison family splashing around like argumentative porpoises. The large-scale administration scenes feel like a disaster preparedness exercise, with the authorities having to handle a highly fluid situation (pun not intended, but dammit, I’m taking it!), and I found the mechanics of how the decisions get made to be quite interesting. The Morrisons, meanwhile, are engaged in little if anything apart from the usual disaster movie cliches of fighting for survival. It all ends in a particularly unconvincing scheme concocted by the Professor, to send the water back down the Thames, and which requires the barrier to be lowered. If you’ve guessed completing this task will require the brave sacrifice of one character, you are ahead of the movie. You may well even be able to figure out who in particular that is: we certainly did.

As disaster porn goes, it’s okay. There’s a slight frisson to be had from seeing places you know, suddenly being under water, and some of the wide shots do a nice job of demonstrating the epic scale of the devastation (as long as the water isn’t moving, anyway). However, it all but entirely fails on the human level, especially if you compare it to something like The Quake. You just don’t care about anyone in peril, so there’s no emotional impact at any point. And I want to have a quiet word with whoever hired Carlyle, then told him he needed to do a London accent…