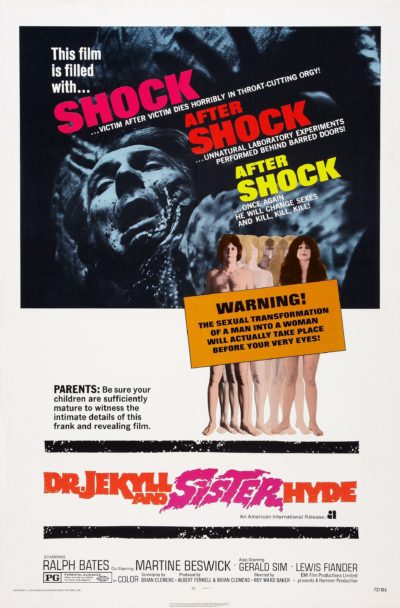

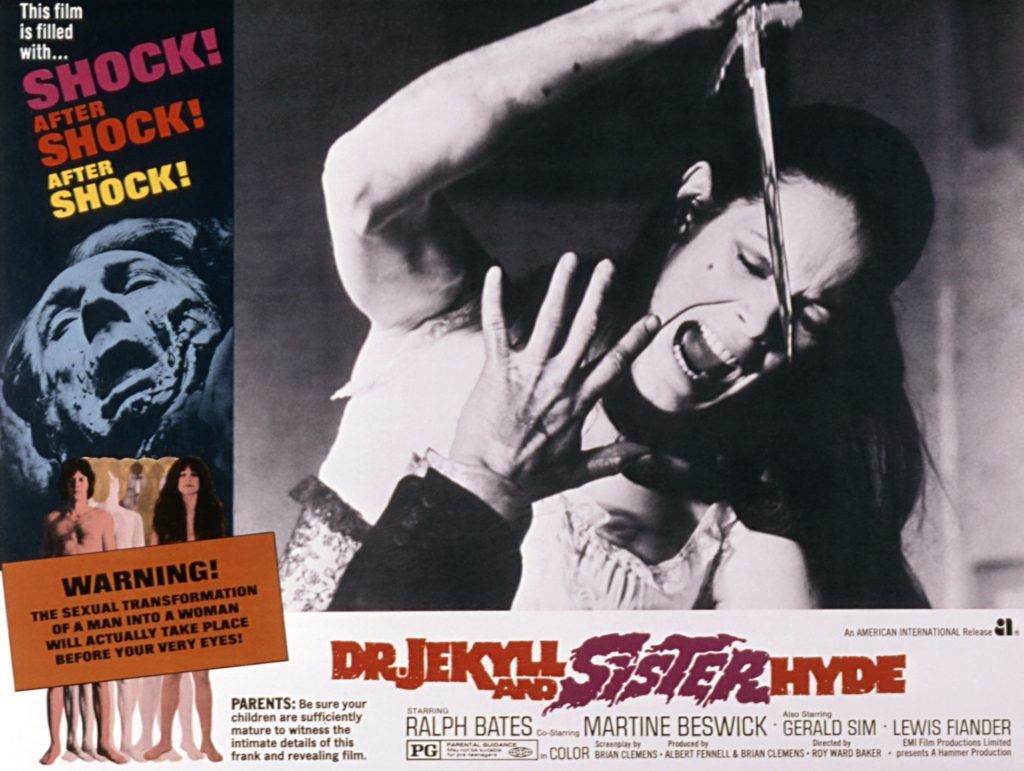

Rating: B-

Dir: Roy Ward Baker

Star: Ralph Bates, Gerald Sim, Susan Brodrick, Martine Beswick

Probably the best name for a film in Hammer history, this is a bit more than a gender-bent version of Robert Louis Stevenson’s multiple personality tale. It adds Jack the Ripper, suggesting Jekyll and Hyde were both participants in the Whitechapel murders, harvesting biological ingredients from the victims. For good measure, Burke and Hare are relocated four hundred miles south, from Edinburgh to London, and about sixty years later. Yet, these various elements mesh surprisingly well in Brian Clemens’s script. Baker directs it with the necessary assurance to sell the rather ludicrous central concept, and in Bates and Beswick, the casting of the two halves is as good as you could have.

In this version, Dr. Jekyll (Bates) is doing research on defeating aging, and is achieving promising results, dosing flies with female hormones. Well, they seem promising, until colleague Professor Robertson (Sim) points out the fly has changed sex. [The pair are clearly on the cutting edge of science, discussing viruses, even though they hadn’t been discovered at the time when Jack was all “down on whores”] Undaunted, Jekyll persists, rather inexplicably downing a shot of his own medicine. It transforms him into a woman (Beswick), whom he explains away to the upstairs neighbours as his widowed sister, Mrs. Hyde. This is a relief to one of them, Susan Spencer (Brodrick), who has a bit of a crush on Dr. Jekyll. But her brother, Howard (Lewis Fiander) is attracted to Hyde. Awkward family dinners loom.

Initially, Jekyll gets the necessary ingredients from corpses provided to him by Byker (Philip Madoc). As Jekyll’s demands increase, Baker sub-contracts out to Burke and Hare, who have no qualms about creating corpses if none can be found. Their crimes eventually catch up with them, in the form of an angry mob. One is hung from a lamppost, and the other dumped in a lime pit and blinded. This cuts off Jekyll’s supply, and after a veiled discussion with Susan, decides to venture into the East End and get the ingredients needed, nice and fresh from (at least, initially) living donors.

Initially, Jekyll gets the necessary ingredients from corpses provided to him by Byker (Philip Madoc). As Jekyll’s demands increase, Baker sub-contracts out to Burke and Hare, who have no qualms about creating corpses if none can be found. Their crimes eventually catch up with them, in the form of an angry mob. One is hung from a lamppost, and the other dumped in a lime pit and blinded. This cuts off Jekyll’s supply, and after a veiled discussion with Susan, decides to venture into the East End and get the ingredients needed, nice and fresh from (at least, initially) living donors.

However, Prof. Robertson is growing increasingly suspicious that his erstwhile pal is beyond the escalating series of murders. Working with the police, he begins surveillance, but Jekyll realizes he’s being watched, and unleashes his feminine alter ego instead to do the dirty work. When Robertson encounters Hyde, she realizes the threat he poses must be addressed. The more Hyde gets out, the more she wants to be out, with the transformation no longer under Jekyll’s control. Hyde decides that Susan’s upper-class hormones – rather than the cheap, slutty ones she has been imbibing – are just what’s needed to make the transition permanent. Needless to say, Dr. Jekyll is not on board with this plan, and is prepared to go to any extremes to prevent it, the struggle eventually proving fatally and mutually destructive.

I guess this is as close as you’ll get to an acknowledgement of Pride month here. I will leave any detailed picking of the psychosexual bones in this, to those who give a shit about such over-analysis. I think it’s fairly obvious that Messrs. Baker and Clemens were not concerned about the representation of transgender individuals in society, and any such scrutiny is likely to say far more about the analyzers than the analyzed. That’s especially true in this case, considering I’m fairly sure the title came first, creating an almost inevitable plot. Personally, I was bothered to a far greater extent, by the way Jekyll/Hyde’s hair changed length between sexes. I mean, where did it go, when she reverted to he? That’s the important thing here, surely.

In tone and style, it shares obvious turf with Hands of the Ripper, but there is considerably more guilt (in a legal sense) attached to the protagonist. Unlike in the original story, it’s not a case of the good Dr. Jekyll fighting against the evil Mr. (or Mrs.) Hyde. In terms of sheer body count here Jekyll and Hyde come off about even; the major difference is in their motivations. You could argue a case that Hyde is actually the better justified, as she is killing for her own survival as an entity. It’s almost – if you squint hard enough, in a dimly-lit room – self-defense, even if admittedly, her victims are not the ones posing a threat. Jekyll on the other hand, kills out of a misplaced belief that his ends justify the means. Tell that to a war crimes tribunal.

In tone and style, it shares obvious turf with Hands of the Ripper, but there is considerably more guilt (in a legal sense) attached to the protagonist. Unlike in the original story, it’s not a case of the good Dr. Jekyll fighting against the evil Mr. (or Mrs.) Hyde. In terms of sheer body count here Jekyll and Hyde come off about even; the major difference is in their motivations. You could argue a case that Hyde is actually the better justified, as she is killing for her own survival as an entity. It’s almost – if you squint hard enough, in a dimly-lit room – self-defense, even if admittedly, her victims are not the ones posing a threat. Jekyll on the other hand, kills out of a misplaced belief that his ends justify the means. Tell that to a war crimes tribunal.

I did like both Bates and Beswick in their roles. I’d not have had them down as looking particularly similar to each other, but when you put them together (something that doesn’t happen in the film, but can be seen in various promo stills, such as at top), the resemblance is striking. There is a bit of a lack of a memorable antagonist here. Initially, it feels as if Professor Robertson will take on that role, then it seems to be Howard Spencer for a bit. Neither end up being particularly useful. However, I’ll take “not particularly useful” over “actively annoying,” as is so often the case with Hammer’s male leads.

The sauce quotient is relatively low, considering the potential inherent in the ideas here. On initial transformation, Mrs. Hyde does seem to be impressed with the presence of breasts. I was reminded of the line by Steve Martin’s character in L.A. Story: “I could never be a woman. I’d just stay at home and play with my breasts all day.” I will admit, 97 minutes of Beswicke doing that would not necessarily have been a bad thing… If falling short of my favourite version of the story, Edge of Sanity, this adaptation is at least considerably more inventive and successful than Hammer’s previous stab, The Two Faces of Dr. Jekyll. We even get a “He hasn’t been himself of late” line. Surely, that alone justifies everything else.

This review is part of Hammer Time, our series covering Hammer Films from 1955-1979.