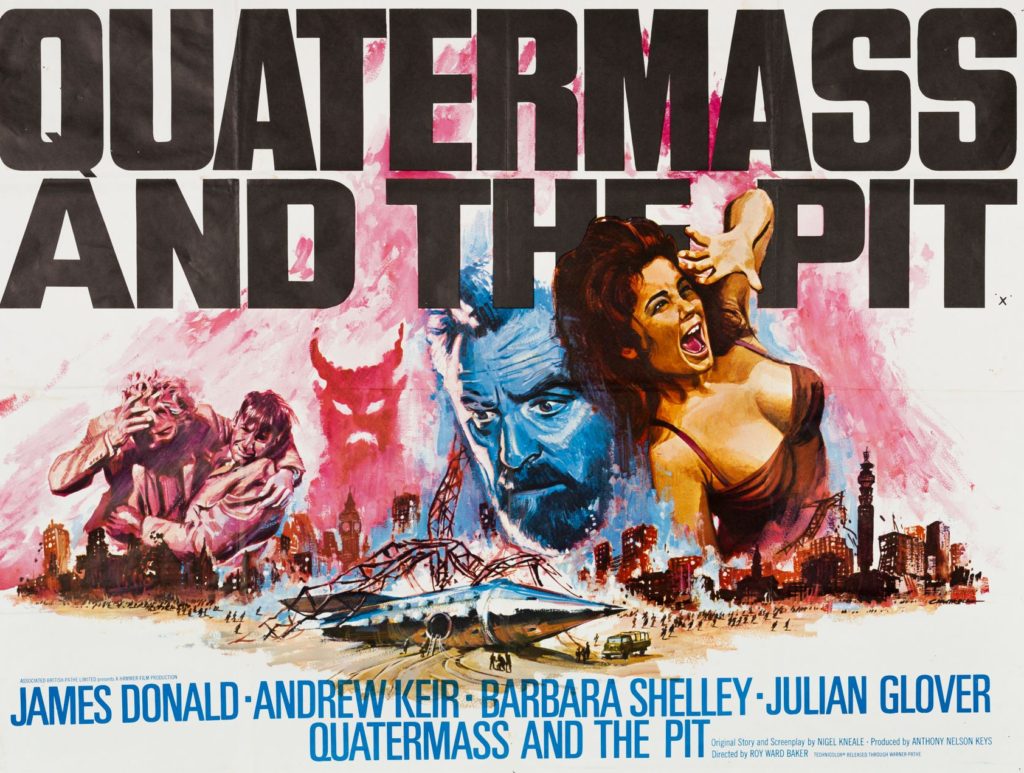

Rating: A-

Dir: Roy Ward Baker

Star: Andrew Keir, James Donald, Barbara Shelley, Julian Glover

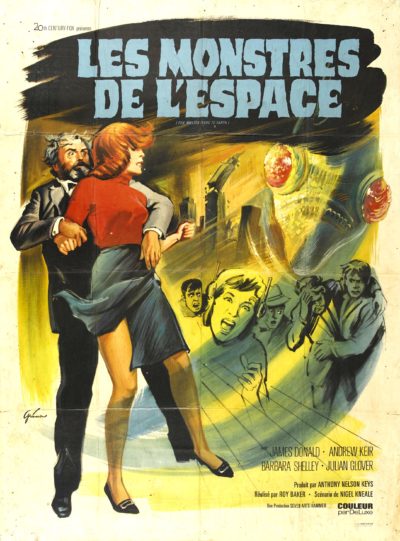

a.k.a. Five Million Years to Earth

1967 had not been Hammer’s finest year. Though it started well enough with Frankenstein Created Woman, they had then given the world a pair of largely woeful pseudo-historical flicks, in The Viking Queen and Slave Girls, sandwiching the least interesting entry in the studio’s least interesting franchise (The Mummy’s Shroud). But with their final release, they delivered a movie which is among Hammer’s best work. I’d go so far as to call it their very best not to star Peter Cushing and/or Christopher Lee. It’s definitely right up there with the peak of the Dracula or Frankenstein franchises, for which they are most renowned. It may also be the greatest British science-fiction film of all time. Okay, not exactly a subgenre notable for its depth. I mean, when The Guardian listed the 20 best in 2014, they needed to include Devil Girl From Mars. Yeah.

But by any standards, this is quality stuff. Like the previous two Quatermass films, it was an adaptation of a Nigel Kneale TV series. But the gap between them was considerably longer here, with the television version debuting nine years previously. Part of the reason was Hammer’s partnership with Columbia, who weren’t interested in the character, and rejected adaptations Kneale submitted, on more than one occasion during the first half of the sixties. By 1966, Hammer were instead working with 20th Century Fox, and the film finally got to end its lengthy stay in development hell. Hammer regular André Morell had played the Quatermass role in the TV version, but didn’t want to repeat the role, so Keir took over.

It’s mostly Kneale’s brilliant script that does the work, dripping out information at impeccable pace. It begins in prosaic fashion, with construction work at the underground station of Hobbs’ End uncovering a large artifact, buried deep below the surface. Investigating are Prof. Quatermass (Keir), archeologist Doctor Roney (Donald), and by-the-book military man, Colonel Breen (Glover). The last-named reckons the artifact is a Nazi propaganda weapon. But as weird incidents continue to mount, the Professor becomes increasingly convinced of a non-terrestrial origin. Worse, the craft may not be as dead as it seems. For the psychic energy it still contains is capable of triggering the worst instincts in susceptible members of the human race – up to and including a lust for genocide.

It’s mostly Kneale’s brilliant script that does the work, dripping out information at impeccable pace. It begins in prosaic fashion, with construction work at the underground station of Hobbs’ End uncovering a large artifact, buried deep below the surface. Investigating are Prof. Quatermass (Keir), archeologist Doctor Roney (Donald), and by-the-book military man, Colonel Breen (Glover). The last-named reckons the artifact is a Nazi propaganda weapon. But as weird incidents continue to mount, the Professor becomes increasingly convinced of a non-terrestrial origin. Worse, the craft may not be as dead as it seems. For the psychic energy it still contains is capable of triggering the worst instincts in susceptible members of the human race – up to and including a lust for genocide.

The film does a great job of mixing historical, religious and scientific motifs. For example, Hobbs’ End gets its name from “hob” being a name for the devil, and the area has a long history of weird incidents. The look of the ship’s inhabitants also resemble the devil archetype. On the other hand, Quatermass is completely devoted to the scientific method, reliant on logic and analysis even when faced with the inexplicable. These two mesh at the end, where the eventual method of countering the threat, while scientific in nature, is also rooted in tradition. It’s all truly smart writing, of the kind it seems we rarely see in big screen sci-fi these days. Kneale manages to address moral issues, without them overshadowing the narrative – another balance which is rarer than it should be.

The trio of performances at the film’s core are all excellent, with Keir, Donald and Glover all bringing something different to proceedings, almost as if they are different aspects of human nature. [I leave it as an exercise to work out who are the id, ego and superego…] The only weakness in the cast is Shelley, and that’s not her fault since her character, scientist, Barbara Judd, feels sharply underwritten in comparison. Naturally, it’s the woman who proves most vulnerable to the alien influence, causing her to be called “overwrought.” Shelley, likely the queen of Hammer, deserved better in her final appearance for the studio. RIP to the actress, who died less than two weeks ago.

Especially in the second half, as things escalate out of control, this seems increasingly a major influence on Tobe Hooper’s expensive piece of wonderful trash, Lifeforce. The director seems to have acknowledged as much, saying of his movie, “I thought I’d go back to my roots and make a 70 mm Hammer film.” I just don’t recall Shelley wandering round naked for the duration. Maybe that’s only in the legendary Japanese version of this Hammer movies, I heard so much about… Snark aside, and much as I love Lifeforce, I can’t argue other than that Quatermass and the Pit is a superior movie. It goes to show that cutting-edge effects, while certainly nice, are by no means required when you have a well-written script and committed, engaging performances from the cast. Baker, in his debut for Hammer, hit this one out of the park, even if he’d never quite reach the same heights again for the studio. This was just one of those films where everyone brought their A-game, and the results are there for all to enjoy and appreciate. Truly a timeless classic.

[November 2010] One of my all-time favourite Hammer films, it completely creeped me out as a kid – the visions in particular – and has stood the test of time very well, despite some flaky FX, especially the “levitating tools”, which are clearly swinging from strings. Otherwise, it’s almost perfect SF, thanks mostly to Nigel Kneale’s script, which creates a marvellously-spooky atmosphere, even in the little touches, as we gradually find out the truth about the craft and its occupants. Watching it now, I couldn’t help notice the strong anti-military stance, with Breen coming over as a real arse.

I’m interested in tracking down the TV series version, from almost a decade previously, for comparison. Keir certainly nails the persona of Quatermass, despite the original choice being Kenneth More, who had starred in Baker’s A Night to Remember. The supporting cast are almost as good, though Shelley’s assistant to Roney is largely kept safely out of harm’s way; well, this was the sixties after all… But it’s still smart, thoughtful science-fiction, which has rarely been done better, even as we approach its fiftieth anniversary.

This review is part of Hammer Time, our series covering Hammer Films from 1955-1979.