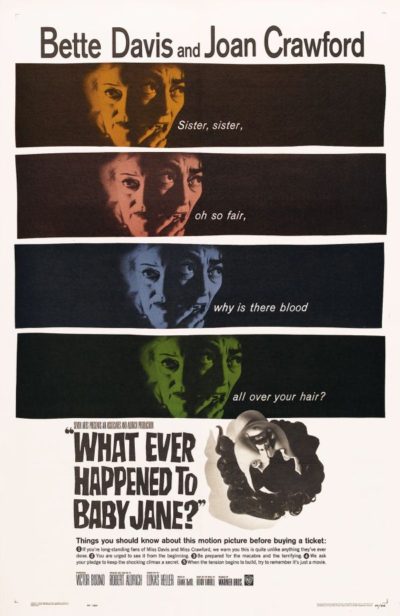

Rating: B-

Dir: Robert Aldrich

Star: Joan Crawford, Bette Davis, Victor Buono, Maidie Norman

With fourteen Best Actress Oscar nominations between Crawford and Davis, this was always going to be the Rumble in the Jungle of performances. It’s likely no surprise that it’s Davis who came out on top in the acting honours. By all accounts, Bette was not exactly magnanimous about it, telling her co-star, “You were so right, Joan. The picture is good. And I was terrific.” This is somewhat ironic, since it was Crawford who had brought Davis on board for the project. Indeed, Joan had largely kick-started the film after reading Henry Farrell’s book of the same name, published in 1960.

It’s the story of two sisters, Jane (Davis) and Blanche (Crawford). Initially, we see 9-year-old Jane as a child star on the 1917 vaudeville circuit, singing a maudlin song about her daddy being in heaven, to a rapt crowd, Meanwhile Blanche watches from the sidelines, disgruntled at the attention her younger sibling is getting. But the worm turns, and by the thirties, Blanche has become a successful actress, to whose coat-tails Jane barely clings. However, in 1935, Blanche is paralyzed after a car accident, blamed on Jane who is found three days later after her latest alcoholic blackout.

That’s just the set-up. We are now in the current era – or “yesterday”, as a caption informs us. The sisters are living in the same house, with Jane at the beck and call of her crippled sister, resenting every moment of it, and revelling in needless cruelty. Blanche, meanwhile, is secretly plotting to sell the house and have Jane committed. When Jane learns of this, it pushes her even further over the edge, and she cuts Blanche off from the outside world entirely. Jane’s psychosis is on full display, hiring a pianist (Buono), with the aim of reviving her career as a child star. Seeing the mid-fifties Davis, squawking “I’ve Written a Letter to Daddy” is proof positive of that, as Blanche tries desperately to find some way to escape the noose tightening around her neck.

That’s just the set-up. We are now in the current era – or “yesterday”, as a caption informs us. The sisters are living in the same house, with Jane at the beck and call of her crippled sister, resenting every moment of it, and revelling in needless cruelty. Blanche, meanwhile, is secretly plotting to sell the house and have Jane committed. When Jane learns of this, it pushes her even further over the edge, and she cuts Blanche off from the outside world entirely. Jane’s psychosis is on full display, hiring a pianist (Buono), with the aim of reviving her career as a child star. Seeing the mid-fifties Davis, squawking “I’ve Written a Letter to Daddy” is proof positive of that, as Blanche tries desperately to find some way to escape the noose tightening around her neck.

We were rather less than convinced by the story. My first question is, why the hell is Blanche being cared for by someone who obviously hates her? They’re clearly not broke. Also, Blanche’s efforts at escape are pretty feeble. I mean, they live right next door to another house, whose occupants are often seen pottering outside – the mother, in particular, is a fan of Blanche. Rather than throwing a note, wouldn’t Blanche have had more luck – oh, I dunno – yelling for help? Breaking a window? Semaphoring for help with flags? However, let’s be honest: you’re not here for the plot. You’re here for two of cinema’s grande dames at the time, slugging it out dramatically.

On that level, at least, the film does deliver. Crawford is hypnotic, as someone whose life basically peaked at the age of nine. But it’s hard to blame Jane for cracking under the incessant pressure of Blanche, leaning on the summoning buzzer with a strength and persistence that belies her disability. She refuses to let her sister have a life of her own, and persistently plays the guilt card of Jane’s role in her confinement. By the end, though, we’ve realized things are far from as clear-cut as we thought, in particular about who is the perpetrator and who is the victim. Though I have to say, for a film which seems to believe in going big or going… bigger, the revelation is almost underwhelming rather than merely understated.

But it’s Davis whom you’ll remember, looking about thirty years older than her actual age, and going for it in a performance which, to be honest, is probably better than the material deserves. Davis got an Oscar nomination, Crawford did not, but it ended up going to Anne Bancroft for The Miracle Worker. In a small victory, Crawford got to give the absent Bancroft’s acceptance speech. This movie was the ground zero of “hagsploitation,” a vein that Davis herself would mine several more time during the twilight of her career in the likes of Hammer films such as The Nanny or The Anniversary,

In particular, she would re-team with Aldrich for the similarly themed Hush, Hush, Sweet Charlotte, though Joan had to drop out of that production, due to “illness”, and was replaced by Olivia de Havilland. Crawford had entries of her own, the most notable being Straight-Jacket; it came courtesy of William Castle, whose The Tingler we discussed earlier in this series. But this remains likely the most highly-respected entry in the genre. Even if you occasionally wonder whether it needs a 134-minute running time, it would be fair to say there’s never a dull moment, especially when Davis is on screen.

This article is part of our October 2022 feature, 31 Days of Classic Horror.

[Original review] When I was young, I used to read a lot of dinosaur books, and there was usually an account of a battle between a T.Rex and a Triceratops. I’m reminded of that here, as two veteran Hollywood leading ladies battle it out for supremacy. Former child star Davis now has to take care of her disabled sister (Crawford), while loathing the fact that her own fame has faded, but her sister still gets fan mail – the film incorporates some of Davis’ less-memorable movies in the earlier sequences. The pair share a common interest, however: making the other’s life miserable. This all-consuming hobby eventually leads to tragedy, to no-one’s real surprise.

Davis is genuinely creepy, trying to cling to her long-gone youth, croaking the song which made her famous. Crawford is a fine foil, though her failure to spot the warning signs will have you shouting “Get out of the house NOW” at the screen. Credit also to Buono, for a schemer willing to (ugh!) flirt with Davis to get at the money he presumes she has. The plot is too coincidental, with people inevitably turning up at precisely the worst moment, and the teenage girl next door (Davis’ real-life daughter) appears to have escaped from Gidget. Otherwise, this is unrelentingly warped and highly creepy. B