Rating: C+

Dir: Terence Fisher

Star: Guy Rolfe, Andrew Cruickshank, George Pastell, Jan Holden

It’s 1829, and a crisis is brewing in colonial India, after a merchant caravan has vanished without a trace. Captain Harry Lewis (Rolfe) believes he’s the man to investigate this, along with the disappearances of over a thousand locals. However, his superior, Colonel Henderson (Cruickshank), goes for some old-school nepotism and gives the job to newly-arrived Captain Connaught-Smith, the son of an old school chum. Disgusted by the subsequent unsurprising lack of progress, even after a mass grave is found, Lewis resigns his commission and begins his own investigation – though he has to be rescued by a mongoose at one point. The culprits are the Thugees, a radical cult which worships the goddess Kali, and under the guidance of their high priest (Pastell), strangle victims to her glory. They have members at all levels of Indian society, making Lewis’s investigation all the more tricky and personally perilous.

This is certainly different from the typical Hammer film, despite the presence of Fisher behind the helm. This was Rolfe’s sole film for the studio, coming before he achieved cult success, first in William Castle’s Mr. Sardonicus, and then surprisingly in the nineties as Andre Toulon in the Puppet Master franchise. At 6’4″ – one inch shorter than Christopher Lee – he cuts a fairly imposing figure, as a moral straight arrow who is prepared to sacrifice his position for principles. It was also Cruickshank’s only Hammer film; he’d shortly go on to a long career in Dr. Finlay’s Casebook. You can find a couple of familiar faces in the supporting cast, most obviously Pastell, recently seen in The Mummy. Glamour model Marie Devereux, who’d go on to be Elizabeth Burton’s stand-in in Cleopatra, makes an impression as a Kali acolyte and Indo-totty. Or two impressions, if you know what I mean, and I think you do.

Of course, Indian actors are largely notable by their absence, outside of Marne Maitland as local leader Patel Shari. The rest range from Cypriots like Pastell through Britons (including future Master in Doctor Who, Roger Delgado, and future Alf Garnett, Warren Mitchell) to the Norwegian Tutte Lemkow, who plays Lewis’s houseboy, Ram Das. Coincidentally, Lemkow also appeared in Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom, which had a similar Kali cult, there playing the Imam who translates the inscription on the headpiece of the Staff of Ra. And if you’re like me, you’ll be racking your brains trying to figure out where else you’ve seen Allan Cuthbertson, the actor playing Connaught-Smith. Let me save you the bother: he was in the classic “Gourmet Night” episode of Fawlty Towers, in the role of the Colonel with a nervous twitch.

Of course, Indian actors are largely notable by their absence, outside of Marne Maitland as local leader Patel Shari. The rest range from Cypriots like Pastell through Britons (including future Master in Doctor Who, Roger Delgado, and future Alf Garnett, Warren Mitchell) to the Norwegian Tutte Lemkow, who plays Lewis’s houseboy, Ram Das. Coincidentally, Lemkow also appeared in Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom, which had a similar Kali cult, there playing the Imam who translates the inscription on the headpiece of the Staff of Ra. And if you’re like me, you’ll be racking your brains trying to figure out where else you’ve seen Allan Cuthbertson, the actor playing Connaught-Smith. Let me save you the bother: he was in the classic “Gourmet Night” episode of Fawlty Towers, in the role of the Colonel with a nervous twitch.

This unquestionably sits outside the horror genre – it’s more an adventure film, again not dissimilar to Indiana Jones. Yet it is certainly among the more vicious of Hammer films, especially considering both the era, and that there’s no supernatural overtones to the violence. There’s a high body-count, and these are human beings being unpleasant to other human beings, not vampires or ill-considered scientific creations. Even 130 years of historical distance (at the time of release) can’t entirely dilute the nastiness. There’s an almost casual nature to the Thuggees’ slaughter which makes it feel particularly callous, and meshes nicely with the depicted British disinterest in the matter initially. The officers of the Raj don’t care that a four-figure count of locals have gone missing. It’s only when their colonial profits are threatened that Something Has To Be Done.

It would be easy for this to have ended up firmly in the “White Man’s Burden” corner, with the British having to save the natives from themselves. However, the script by David Z. Goodman (another one-and-done as far as Hammer are concerned, though he’d go on to write both Logan’s Run and Straw Dogs) is rather more nuanced. Connaught-Smith is depicted as a useless idiot, and gets the fate he deserves, while Henderson is a desk jockey, for whom our hero has little time. Lewis is the only sympathetic figure among the colonists. Admittedly, the Indians aren’t depicted in much better light. Aside from the cultists, it’s mostly a cliched roll-call of swindling merchants, mendicants, servants, etc.

Pointedly, when Lewis is seeking information on the missing Ram Das, one person to whom he talks replies, “He is not our kind. I am Muslim, he is Hindu.” Worth remembering that, when this came out, the partition of India had taken place only a dozen years previously. There’s also a nod to the future tumult in store for the colony, in particular the Indian Mutiny of 1857, when Lewis warns Henderson, “The Indians are dissatisfied. Mark my words, before years have gone by, they’ll express dissatisfaction in a way that won’t be pretty.” However, the central premise of the film is on rather shakier historical grounds. Some modern scholars doubt whether the Thuggees ever were a thing, certainly not to the level claimed by the British, and may indeed have been constructed as much out of fear and ignorance as any facts.

Goodman wrote his script based on the autobiography of Major General Sir William Sleeman, the officer who claimed to have extinguished the Thuggee cult, so it’s hardly a surprise there’s no room for doubt here. The film ends with his quote, “If we have done nothing else for India, we have done this one good thing.” Yet as the end credits roll, it’s not quite clear what Lewis’s role in the “one good thing” might be. Sure, he managed to cut off the head of the snake. But the film opened with that same head telling a story where Kali fought a monster, and “from each drop of his blood, a new monster spawned.” The downbeat depiction seen here, suggests the monster Lewis fought may behave in the same way, and the caption-based coda, detailing Sleeman’s subsequent triumph over the Thuggees, hardly feels justified.

This review is part of Hammer Time, our series covering Hammer Films from 1955-1979.

[October 2010] Truth be told, there’s not much actual strangling going on here, especially in the first hour, which sees Captain Harry Lewis (Rolfe) investigating the disappearances of, literally, thousands of people in and around the titular Indian city. His boss, Colonel Henderson (Cruickshank) only takes him seriously when trade caravans start to vanish, but doesn’t bother letting Lewis look into things, instead appointing Captain Connaught-Smith, a chum who went to the same school (the part is played by Allan Cuthbertson, who was Colonel Hall in the “Gourmet Night” episode of Fawlty Towers). Lewis continues to dig, comes to the attention of the Kali cult leader (Pastell), and is captured, though is released, through what can only be a called a deus ex mongoosea. But with the cult preparing to take down the caravan to end all caravans, about to leave Bombay under the eye of Connaught-Smith, they realize that letting go the Westerner who was investigating them, may not have been such a wise idea.

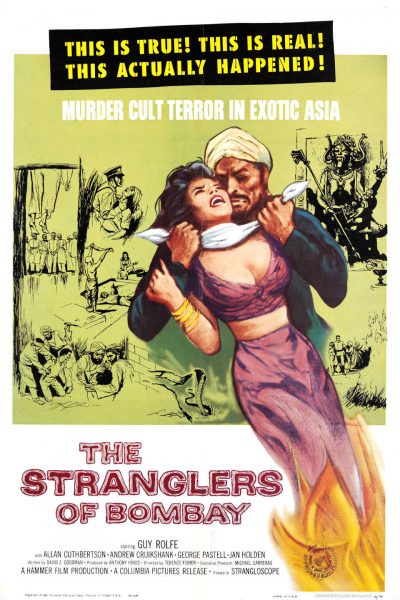

I like how the poster screams, “This is true! This is real! This actually happened!” as if one of those statements isn’t actually enough. Well… It’s based on true events, though the dying out of the Thuggees perhaps had as much to do with the arrival of railway, providing cheap, safe transport through the rural areas in which they operated, as the efforts of the British army. Still, who’d go see a movie about Indian trains? That aside, this is mostly pedestrian stuff, that feels more like a history book on the topic than an exciting action-adventure yarn, despite some similarities to The Temple of Doom. Rolfe might as well be made out of cardboard, and there’s little sense of danger. The only exception is the attack on the caravan, as the Thuggees materialize out of the jungle around Connaught-Smith and his men; it’s a nicely-creepy moment, in what is otherwise a fairly dull and forgettable effort, with little of the style we’ve come to expect from Hammer. D+