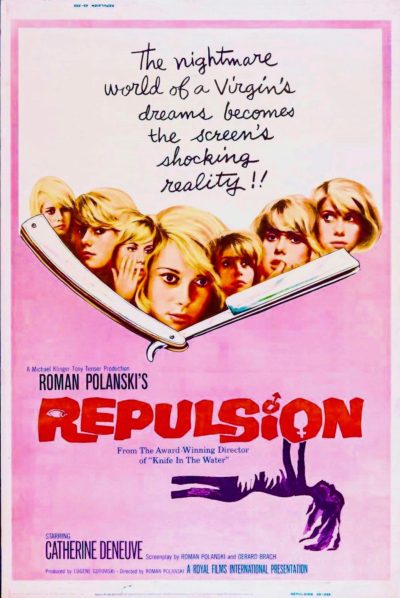

Rating: B-

Dir: Roman Polanski

Star: Catherine Deneuve, John Fraser, Yvonne Furneaux, Ian Hendry

Polanski’s first English language feature, and second overall, showcases certain elements that he’d revisit on a number of occasions thereafter. Indeed, this could be considered the first in his “Mentally troubled resident living in a creepy apartment building and going increasingly mad” trilogy. Catchy title. The focus here is on Carol Ledoux (Deneuve), a Belgian beautician living with her sister, Helen (Furneaux, whom we saw in The Mummy), both of them occupying a South Kensington flat. Their relationship is strained by Carol’s dislike of Helen’s boyfriend, Michael (Hendry), and Carol herself is being relentlessly pursued by the borderline obsessive Colin (Fraser). When Helen and Michael go off on holiday, the resulting vacuum triggers an emotional and mental implosion in Carol, manifesting itself in violent outbursts against anyone unlucky enough to enter the apartment.

There are elements here which are a bit clunky and obvious. The decaying meat and vegetables, for example, or the cracks that open up in the walls of the flat, are just too blatant symbols for Carol’s breakdown. Yet Polanski keeps going back to them, when he’d have been better to stand back and let Deneuve’s quietly impressive performance do the talking. It’s clear from the very start, with its extreme close-up of her unblinking eye, that she has issues – she drifts off into a mental haze, sometimes for days at a time. While those around her realize there’s something up, they have no idea how to handle it, or how deep the problem lies. “You ought to go out, go to a movie or something,” is a work colleague’s well-meant, if totally useless advice. Carol’s reluctance to share her troubles – also symbolized by her resistance to anyone entering the apartment – exacerbates the situation.

It’s hinted that the origin of Carol’s problem may lie back in her youth. While there’s nothing specific detailed, we get ominous-feeling shots of family pictures, particularly one of a young Carol at the end where she already looks emotionally dead inside. For whatever reason, she is unable to handle affection. particularly of the physical kind, but even other people’s. Yet she simultaneously seems lured in by it: witness her sniffing Michael’s shirt in the bathroom, then rushing to throw up. It’s as if she wants to have a relationship, yet is incapable of achieving the necessary human connection. She has no clue how to respond to any such attempts, e.g. just walks away from Colin when he asks her out.

It’s hinted that the origin of Carol’s problem may lie back in her youth. While there’s nothing specific detailed, we get ominous-feeling shots of family pictures, particularly one of a young Carol at the end where she already looks emotionally dead inside. For whatever reason, she is unable to handle affection. particularly of the physical kind, but even other people’s. Yet she simultaneously seems lured in by it: witness her sniffing Michael’s shirt in the bathroom, then rushing to throw up. It’s as if she wants to have a relationship, yet is incapable of achieving the necessary human connection. She has no clue how to respond to any such attempts, e.g. just walks away from Colin when he asks her out.

There is a question as to how much of what is depicted has a basis in reality. The murders clearly do. The hands coming out of the walls toward Carol? Not so much. And as a result, I feel that throws everything else into a bit of a grey area. Is Carol actually raped? Or is that just another manifestation of her fears? In the end, it probably doesn’t matter. It’s real to her, dammit. However, I can’t say I felt it worked particularly well as a “horror” film, quotes used advisedly. It felt more like a sad drama about mental illness. When the monster is chained up inside someone else’s head, there’s not much sense of threat. Though having had my quota of psycho bitch ex-girlfriends, I suppose I should be grateful I escaped with only the eyes on my video sleeves gouged out. True story, folks.

We must address the obvious elephant in the room here. A film about a woman driven into madness by the predatory assaults of men, is on thin ice (to put it mildly) when the director was charged with drugging and sodomizing a 13-year-old girl, subsequently fleeing the country. Over 40 years later, Polanski still hasn’t returned to the US. Now, I’m normally pretty good at separating the artist from their art – hello, Klaus Kinski. But it does leave this feeling like a sexual harassment training seminar given by Harvey Weinstein. The scene where Colin’s pals joke about getting Carol over and plying her with drink, so he can take advantage of her, has particularly not aged well in this light. Even if depicted negatively, you still have to cringe at lines like, “They’re all the same, these bloody virgins. They’re just teasers, that’s all,” or “By the end of the evening, she’ll be begging for it… She’ll weep with gratitude.” Oof.

While widely influential, this seems particularly to have had an impact on Abel Ferrara. I read one review of Repulsion which called Driller Killer an “unofficial remake,” but I think a closer comparison is probably Ms. 45, in ways both big and small. As well as the stunningly beautiful female protagonist, whose sanity disintegrates after a sexual assault, we have the nosey neighbour with a dog, the callous and unfeeling employer, and her targets being the men she perceives – rightly or wrongly – as posing a danger to her. Both movies also have an early sequence in which the woman gets cat-called while walking through the mean streets of the urban environment, foreshadowing the threat posed by predatory men. But perhaps most striking is the rape scene here, unfolding without Carol being able to make a sound recorded by the camera. It’s a definite precursor to the experiences of the mute heroine in Ms. 45.

While widely influential, this seems particularly to have had an impact on Abel Ferrara. I read one review of Repulsion which called Driller Killer an “unofficial remake,” but I think a closer comparison is probably Ms. 45, in ways both big and small. As well as the stunningly beautiful female protagonist, whose sanity disintegrates after a sexual assault, we have the nosey neighbour with a dog, the callous and unfeeling employer, and her targets being the men she perceives – rightly or wrongly – as posing a danger to her. Both movies also have an early sequence in which the woman gets cat-called while walking through the mean streets of the urban environment, foreshadowing the threat posed by predatory men. But perhaps most striking is the rape scene here, unfolding without Carol being able to make a sound recorded by the camera. It’s a definite precursor to the experiences of the mute heroine in Ms. 45.

I wonder if the issues in production perhaps ended up working to the benefit of the end result, by helping generate the feeling of alienation at its core. Neither Polanski nor Deneuve were fluent in English, which must have made director-actress communication a bit problematic. His relationship with Furneaux was also strained, and Ian Hendry didn’t help matters with a fondness for an extended and liquid lunch. Still, considering Polanski’s lack of feature experience, it does a good job of taking you inside the world of someone suffering from mental illness. At least, it feels like it does: I can’t speak to the clinical authenticity, obviously. You’d need to speak to the psycho bitch ex-girlfriend about that…

This article is part of our October 2022 feature, 31 Days of Classic Horror.