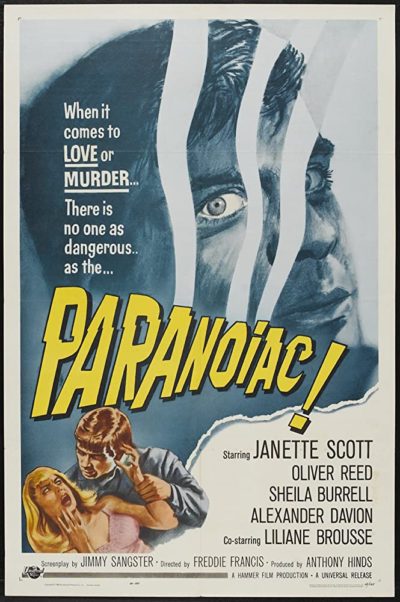

Rating: C+

Dir: Freddie Francis

Star: Janette Scott, Oliver Reed, Alexander Davion, Sheila Burrell

After the economic failure of Phantom of the Opera, Hammer switched back to smaller projects, with long-time scribe Jimmy Sangster writing a series of psychological horrors, without the expensive period trappings. This one centers on the dysfunctional Ashby family: the parents died in an accident, and teenage son Tony took his life a few years later. Now there’s mentally-troubled Eleanor (Scott) and drunken rake Simon (Reed), who is looking forward to getting his inheritance, instead of relying on the disapproving family lawyer who administers the trust fund. It’d be even nicer if he could get Eleanor committed as insane… However, that hope is derailed when Tony apparently returns from the dead, after eight years – just in time to take over the family. But it is the “real” Tony or an impostor? And if it’s the latter, at whose behest has the cuckoo been inserted into the nest?

It’s ironic to see Reed playing an alcoholic asshole, given that’s basically what he became for the majority of his later life. Sangster’s script pulls off a number of twists that I didn’t see coming, though the ending appears to abandon all semblance of sanity and heads into Gothic loopiness. While not all bad – it gives Reed the chance to engage in some excellent, manic face-pulling – it doesn’t really fit with the tone set in the opening 70 minutes, which are much more prosaic and down-to-earth. Indeed, you could say that Reed doesn’t really fit with the rest of the performances, which are a good deal more laid-back by comparison. Interesting that Hammer also went back to black-and-white for this one: whether as a cost-cutting measure, or to invoke comparisons with Psycho is hard to say, but it’s quite effectively used. Even though I watched this at the end of a really long day, it kept me awake and adequately interested, when a lesser film would have failed to stave off unconsciousness.

It’s ironic to see Reed playing an alcoholic asshole, given that’s basically what he became for the majority of his later life. Sangster’s script pulls off a number of twists that I didn’t see coming, though the ending appears to abandon all semblance of sanity and heads into Gothic loopiness. While not all bad – it gives Reed the chance to engage in some excellent, manic face-pulling – it doesn’t really fit with the tone set in the opening 70 minutes, which are much more prosaic and down-to-earth. Indeed, you could say that Reed doesn’t really fit with the rest of the performances, which are a good deal more laid-back by comparison. Interesting that Hammer also went back to black-and-white for this one: whether as a cost-cutting measure, or to invoke comparisons with Psycho is hard to say, but it’s quite effectively used. Even though I watched this at the end of a really long day, it kept me awake and adequately interested, when a lesser film would have failed to stave off unconsciousness.

[Also starring: Maurice Denham, who plays family lawyer Mr. Kossett, had a long career as a character actor. His voice, from Night of the Demon, is heard on the opening of the Kate Bush song, “Hounds of Love”: “It’s in the trees! It’s coming!”]

[July 2010]

By odd coincidence, we watched this the same week as The Devils, forming an “Oliver Reed burns to death” double-bill. Uh, I should probably have had a spoiler tag around that. 🙂 Meanwhile, Chris let out a little shriek at seeing Scott’s name in the opening credits. She hadn’t realized that the actress had a career, beyond what was referenced in the opening song of The Rocky Horror Picture Show: “And I really got hot, when I saw Janette Scott fight a Triffid that spits poison and kills…” Yup, she’s the leading lady here. The daughter of Thora Hird and future wife of Mel Torme, Scott is still alive, now in her eighties.

Initially, this plays not unlike Taste of Fear, with an emotionally-fragile young woman being haunted by someone that is supposed to be dead, and no-one believing her. However, that aspect proves to be fleeting. Her dead brother proves to be a real person, though as we relatively quickly discover, is not who he claims to be. It’s all a result of the large inheritance into which Eleanor and Simon will shortly be coming, of £500,000. That’d be more than ten million quid in current money, which does explain everyone’s interest. Simon wants Eleanor committed as insane, so he can get it all. But the arrival of the newcomer would mean it gets split three ways instead. Simon isn’t happy, obviously. But Eleanor is delighted, to the point where her feelings are clearly more than fraternal.

There’s a point in this where the tone suddenly shifts. It comes when Tony is investigating late-night organ music from the family chapel – yeah, the Ashbys are so rich, they have one of those. He opens the door, and a masked figure swings a hook at him. It’s definitely a WTF? moment, being an abrupt change from the understated and psychological aspects we’ve seen earlier on. Thereafter, the film certainly becomes rather more lurid, and throws no shortage of bizarre behaviour at the viewer. I tend to find this increasing Gothic insanity (both literally and figuratively) less effective than, say, the relatively staid but far more tense scene on the edge of a cliff (shown, top), when a picnic goes horribly wrong.

There’s a point in this where the tone suddenly shifts. It comes when Tony is investigating late-night organ music from the family chapel – yeah, the Ashbys are so rich, they have one of those. He opens the door, and a masked figure swings a hook at him. It’s definitely a WTF? moment, being an abrupt change from the understated and psychological aspects we’ve seen earlier on. Thereafter, the film certainly becomes rather more lurid, and throws no shortage of bizarre behaviour at the viewer. I tend to find this increasing Gothic insanity (both literally and figuratively) less effective than, say, the relatively staid but far more tense scene on the edge of a cliff (shown, top), when a picnic goes horribly wrong.

However, this is probably most notable for being the Hammer debut of Freddie Francis, among the directors most associated with the studio (I would likely put him behind only Terence Fisher). Francis – who had done uncredited work on Day of the Triffids, in particular on the scenes featuring Scott! – had began his career as a cinematographer, winning an Academy Award for his work on Sons and Lovers in 1960. That opened the door to directorial work, though it’s perhaps sad that he spent most of his career applying his skills to low-budget movies. In the horror genre, while he worked for Amicus and Tyburn as well, it is his movies with Hammer for which Francis is best remembered. Here, some of his filter work is particularly notable, though perhaps as much a distraction as an enhancement.

The idea for the film had been sitting around Hammer for more than a decade. They had bought the rights to Brat Farrar, the book by Josephine Tey on which Jimmy Sangster based his script, back in 1952. But it was only after Psycho, and the success of Hammer’s subsequent similar psycho-thrillers, that this was deemed viable. The presence of a mummified corpse here, which I am fairly sure was not part of the source novel, feels particularly inspired by Hitchcock’s masterpiece. The book subsequently became a British TV mini-series in 1986, which is available on YouTube. But that adaptation didn’t have Oliver Reed menacing people with a fistful of darts, and so has consequently been largely consigned to the memory hole of forgotten media.

This review is part of Hammer Time, our series covering Hammer Films from 1955-1979.