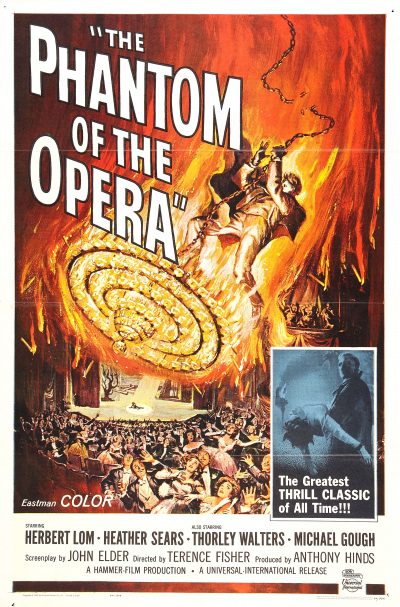

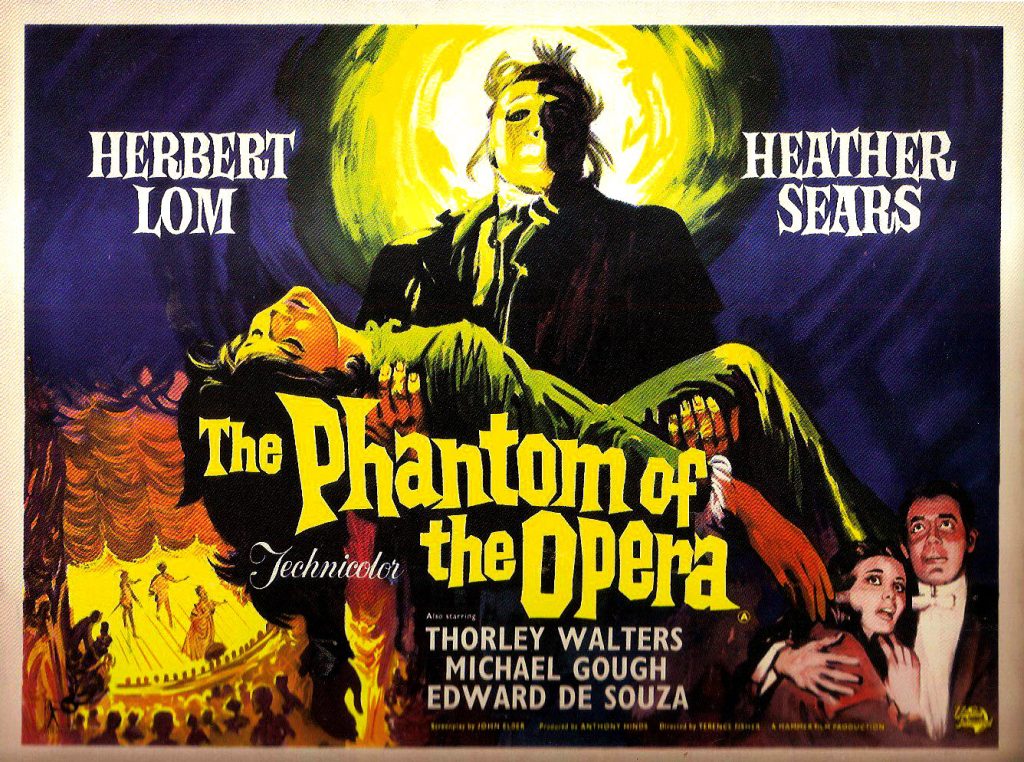

Rating: C+

Dir: Terence Fisher

Star: Herbert Lom, Heather Sears, Edward de Souza, Michael Gough

[Original review] What? No songs? Yeah, we kept breaking into Music of the Night through this one, but it’s not really the film’s fault that I’m listening to the Lloyd-Webber soundtrack as I write this. The story shouldn’t need much description, but there are some interesting differences from other versions. Here, the Phantom (Lom) is actually a disgruntled composer, who sold the publishing rights for his work to Lord D’Arcy (Gough), only to have him claim the compositions as his own and publish them. An accident involving nitric acid at the printers leads to the Phantom’s disfigurement and seclusion in the opera house, from where he sabotages D’Arcy’s attempts to stage the opera. But he is seduced by the voice of Christine (Sears), and kidnaps her to teach her the proper delivery of his work. For obvious reasons, that disturbs her boyfriend, theatrical producer Harry Hunter (de Souza), who heads off into the sewers beneath the theatre in search of his missing beloved.

There’s not much threat to this Phantom, who comes over as an almost entirely sympathetic figure, especially at the end, where his behaviour is positively heroic. If there’s a villain in the piece, it’s D’Arcy, who oozes with slime as he tries to convince Christine to go back to his apartment for a little late-night “singing practice.” The film seems to be building towards a confrontation between him and the Phantom, particularly given their previous history, but this angle is never fully-developed. The other aspect I was surprised to see omitted is that there is absolutely no romantic chemistry between the Phantom and Christine: he is just her teacher, and appears to be from the Jack Bauer school of music tuition. He slaps her about, makes her sing scales until she falls into unconsciousness, then pours sewer water on her to revive her – he makes Simon Cowell seem gentle in comparison. Like the rest of the film, it’s a different approach from every other adaptation, but the various pieces never quite come together in the way that they should, and the result is a good deal less than the sum of the parts.

There’s not much threat to this Phantom, who comes over as an almost entirely sympathetic figure, especially at the end, where his behaviour is positively heroic. If there’s a villain in the piece, it’s D’Arcy, who oozes with slime as he tries to convince Christine to go back to his apartment for a little late-night “singing practice.” The film seems to be building towards a confrontation between him and the Phantom, particularly given their previous history, but this angle is never fully-developed. The other aspect I was surprised to see omitted is that there is absolutely no romantic chemistry between the Phantom and Christine: he is just her teacher, and appears to be from the Jack Bauer school of music tuition. He slaps her about, makes her sing scales until she falls into unconsciousness, then pours sewer water on her to revive her – he makes Simon Cowell seem gentle in comparison. Like the rest of the film, it’s a different approach from every other adaptation, but the various pieces never quite come together in the way that they should, and the result is a good deal less than the sum of the parts.

[Also starring: The rat-catcher who gets stabbed in the eye is Patrick Troughton, the second incarnation of Doctor Who]

[July 2010]

At one point, Universal had intended to do a version of Gaston Leroux’s novel in-house, but after seeing the success of Dracula, turned the project over to Hammer. They took their time: originally announced in February 1959, this took more than three years to reach the screen. At one point, Cary Grant, who had expressed interest in working for Hammer, was linked to the project. He’d certainly have made an interesting Phantom: I imagine the romantic aspects might well have been played up if that had come to pass. Instead, the role went to the future Chief Inspector Dreyfus from the Pink Panther films. Lom said of his role, “The Phantom wasn’t given enough to do, but at least I wasn’t the villain.”

That was played by Gough, who looks a bit like Benedict Cumberbatch. He makes for a decent, and very hissable, bad guy though never receives the comeuppance which he deserves. Towards the end, Lord D’Arcy is confronted by the Phantom, and rips off his mask, only to run off like a little aristocratic bitch at the sight of the acid-scarred face beneath. That’s it. The film largely limps to a conclusion thereafter, with far too much operatic faffing about for the climax of a horror film. However, Sears does a good job of faking her singing, lip-syncing to the track provided by soprano Patricia Clark.

As well as a B-literary horror villain in the Phantom, the rest of the cast are largely Hammer’s B-roster too, with any number of faces you’ll vaguely recognize from elsewhere. Marne Maitland, Thorley Walters and the ever-present Michael Ripper (as a cabby) are among the regulars in supporting or cameo roles here. Apart from the man who’d become Doctor Who as noted above, perhaps the most notable presence is one of the opera house cleaning ladies. She is played by Miriam Karlin: a decade later, she’d be the cat lady killed by Alex in A Clockwork Orange.

It’s nice that the Phantom is not entirely alone in his lair beneath the venue. Perhaps in a hangover from the Cary Grant plans, he has a dwarf minion who gets to do all the bad stuff, while his master maintains distance and plausible deniability. This henchman was the one who saved the Phantom, after his unfortunate encounter with nitric acid led to him leaping into the Thames and being flushed into the sewers. It’s a bit of a weird relationship, about which I’d have liked to know more.

It’s nice that the Phantom is not entirely alone in his lair beneath the venue. Perhaps in a hangover from the Cary Grant plans, he has a dwarf minion who gets to do all the bad stuff, while his master maintains distance and plausible deniability. This henchman was the one who saved the Phantom, after his unfortunate encounter with nitric acid led to him leaping into the Thames and being flushed into the sewers. It’s a bit of a weird relationship, about which I’d have liked to know more.

Fisher brings his usual lush eye to proceedings, and it feels as is Hammer pushed the boat out a bit further than usual, with regard to expenses. Some of their period pieces feel obviously limited, but that seems less so here. Having an actual opera house – no longer apparently in Paris – probably helps there. That part went to Wimbledon Theatre; in 1999, I saw Leslie Grantham and Bonnie Langford (another Who connection) in Peter Pan there. In hindsight, I’m a bit disappointed that performance did not conclude with anyone being crushed beneath a chandelier.

If the production values and performances are fine, it’s the story which drops the ball, with no real sense of conflict and mixed messages as to who the antagonist is supposed to be. Additionally, it has one of the most abrupt endings in Hammer history. Oh, they rarely hung around, to be sure, but this one goes from full-steam ahead to end credits rolling in less than 30 seconds, in a particularly jarring way. Combined with a lack of resolution for D’Arcy, it is an unsatisfactory way to leave your audience. While not irredeemable, the film’s lack of success at the time is completely understandable.

This review is part of Hammer Time, our series covering Hammer Films from 1955-1979.