Rating: C-

Dir: Roger Corman

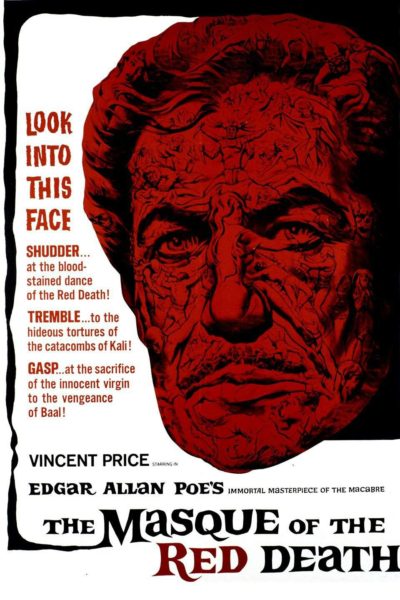

Star: Vincent Price, Jane Asher, Hazel Court, David Weston

For the penultimate entry in his Poe cycle, Corman moved production across the Atlantic, courtesy of a co-production deal AIP had with British studio Anglo-Amalgamated. That helps explain the presence of so many British actors, including future baker to the stars Asher, and Patrick Magee. Court should also be familiar, having starred in a number of Hammer films, most notably as Elizabeth, the main love interest in The Curse of Frankenstein. Subsidies from this Transatlantic approach helped allow a bigger budget, and the film was also able to take advantage of sets left standing from the shooting of Becket. It had been a story Corman had been seeking to make for some time, but he’d delayed it over concerns about similarities to Ingmar Bergman’s The Seventh Seal. He’s not wrong.

It’s based on Edgar Allan Poe’s 1842 story of the same name, though since that clocks in at under 2,500 words, it required a lot of fattening up by the writers. This included adding in another Poe story, Hop-Frog, and also elements from Auguste Villiers de l’Isle-Adam’s Torture by Hope. But I still feel the story is easily the weakest element here, though to be fair, it feels as if Corman is not especially interested in narrative. At points, it feels more like a precursor to his later LSD-flick, The Trip. Since that’s one of the very few films I have abandoned in the middle at a theatre, this is not exactly a ringing endorsement.

The main change is making Prince Prospero (Price) into a Satanist. It’s one of the earliest depictions of such, earlier films having merely hinted darkly at such things. He is, in fact, a bit of a bastard, to the point you can argue whether this or Matthew Hopkins in Witchfinder General is the biggest bastard in the Price filmography. He rules his territory in medieval Italy with an iron hand, delighting in roaming the countryside and striking fear into his vassals. Though perhaps not as much fear as the titular plague, which is ravaging the land, and is given human form by a mysterious figure in a red cloak. [Except at the end, he is played, uncredited, by John Westbrook, whose sonorous voice has more than an echo of Christopher Lee to it]

The main change is making Prince Prospero (Price) into a Satanist. It’s one of the earliest depictions of such, earlier films having merely hinted darkly at such things. He is, in fact, a bit of a bastard, to the point you can argue whether this or Matthew Hopkins in Witchfinder General is the biggest bastard in the Price filmography. He rules his territory in medieval Italy with an iron hand, delighting in roaming the countryside and striking fear into his vassals. Though perhaps not as much fear as the titular plague, which is ravaging the land, and is given human form by a mysterious figure in a red cloak. [Except at the end, he is played, uncredited, by John Westbrook, whose sonorous voice has more than an echo of Christopher Lee to it]

On one such trip, he abducts Francesca (Asher), and brings her back to his castle, along with her lover (Weston) and father, to ensure her compliance. The new arrival does not sit well with Prospero’s existing consort, Juliana (Court), who is prepared to go to any lengths to get the Prince’s attention back: in particular, she wants to join him in his worship of Satan. But he’s largely distracted, partly by Francesca, partly by his upcoming extended party for the landed gentry, which he insists is going ahead despite the plague outside the castle’s walls. The entertainment offered (to the viewer and/or the attendees) includes Gino and Ludovico playing Russian Roulette with poisoned daggers – and, it appears, death by falcon.

Things only escalate from there. Another part of the entertainment, midget Hop-Toad, gets his revenge on one of the guests who humiliated his partner, Esmeralda, by setting him on fire. [While Hop-toad is a genuine little person, portrayed by Skip Martin, Esmeralda is played by seven-year-old Verina Greenlaw, dubbed with an adult woman’s voice. It’s possibly the creepiest thing the film has to offer] At the masquerade, one attendee has spurned Prospero’s strict orders not to wear red. No prizes for guessing who. The guest gradually brings death to all in attendance, despite the Prince’s exhortations that he deserves to serve alongside Satan in hell. “Death has no master”, says the figure. Yeah, that’s clearly not an encounter which is going to end well for Prospero.

It may seem odd to say this, in regard to films about vampires, etc. but I prefer the more grounded approach to their stories which Hammer took. Despite the obvious supernatural overtones, there never seemed any doubt that Dracula was “real”, and if you take that as a given, just about everything else followed in a logical sense. Here, that definitely isn’t the case. Maybe it all makes sense internally, yet that seems to rely on no logic at all. For example, the falcon attack mentioned above comes out of close to nowhere. The same goes for the Hop-toad subplot, which feels exactly like it is: from a completely different story altogether.

It may seem odd to say this, in regard to films about vampires, etc. but I prefer the more grounded approach to their stories which Hammer took. Despite the obvious supernatural overtones, there never seemed any doubt that Dracula was “real”, and if you take that as a given, just about everything else followed in a logical sense. Here, that definitely isn’t the case. Maybe it all makes sense internally, yet that seems to rely on no logic at all. For example, the falcon attack mentioned above comes out of close to nowhere. The same goes for the Hop-toad subplot, which feels exactly like it is: from a completely different story altogether.

If you are prepared to put such humdrum concerns as narrative out of the way, there are still qualities to admire. You can certainly see its influence on future film. The Devils and Salo both seem particular cases, in which the rich and powerful seem more or less deliberately oblivious to things falling apart around them. The striking colour palette of the former also echoes this, which undeniably does look gorgeous, with tableaux like the one above, resembling a medieval painting. In keeping with the Corman tradition of giving up-and-comers their chance, the cinematographer here was Nicolas Roeg, who’d go on to renown in his own directorial career. The use of red here as a harbinger of death perhaps foreshadows a similar technique used by Roeg in Don’t Look Now.

Price is solid as ever, but if there’s a performance here I liked, it’s that of Court. Despite her Satanic aspirations, Juliana comes over as something of a sympathetic character. She’s just blinded by her (horrifically misplaced, it must be said) affection for Prospero. Perhaps part of my overall dissatisfaction is that there were plenty of potentially interesting stories to be told here. The Prince’s might be the least of them, especially when Corman’s focus is more on the visual side. Some of the attempts I’ve seen to shoehorn recent events into critiques of this, are frankly a bit cringeworthy [COVID’s 1% death rate, and that heavily weighted to the old, is not exactly the plague]. But overall, I’m likely most in agreement with producer Sam Arkoff, who described this adaptation as “too arty farty”.

This article is part of our October 2022 feature, 31 Days of Classic Horror.