One of the benefits of streaming services like Tubi is, they’re not constrained by traditional notions of what constitutes a feature film. While festivals and anthologies do provide an outlet for shorts, they’re not really available to movies of a certain length, in the thirty to seventy minute category. They’re too long for a shorts program, but a theatrical or even a DVD release is highly unlikely. Tubi to the rescue, offering a way for those awkwardly-sized films to find an audience. Which is fortunate for Jordan-Kane Lewis, since it’s how I saw Nothing Goes, a 53-minute entity, which followed up his similar length (62-minute) feature debut, A Touch of Vengeance.

He operates out of the town of Sheffield, in the North of England. It’s not exactly a traditional cinematic location, being better known for steel-making and – in Film Blitz Towers anyway – eighties bands like Cabaret Voltaire and Heaven 17. Though it has provided a backdrop to some memorable works, including Threads and Four Lions. Lewis recently completed production on his third film, and a fortuitous encounter on Facebook led to him answering some questions about the joy of brevity, the importance of organization, and cinematic ice baths!

Tell us a bit about your background. How did you get into film-making?

My dad and older brother were film buffs. My dad would show me all sorts of films—often foreign, but typically more mainstream ones—whereas my brother would introduce me to everything from horror to Hong Kong action films, I remember a lot of Jet Li films like Unleashed, being a repeat watch! Even exposing me to the exploitative boom of the early 2000s, like Hostel and Saw. Definitely stuff I probably shouldn’t have been watching. But I wouldn’t change it for anything as it’s likely a big part in why I pursued film-making in the first place. When I was younger, I started by making really bad stop-motion animations on an old phone. I also used the family camcorder to shoot little films, mainly so I could mess around with After Effects. Inadvertently, I was teaching myself techniques that I still use today—like masking, keyframing, editing (cutting), and animation. Even back then, I never liked being in front of the camera—I was always obsessed with what was happening behind the scenes.

What triggered your jump from shorts to longer-format work?

Really even when I was shooting shorts I was trying to tell bigger stories so a medium to feature is my Goldilocks zone. Enough time to tell a story which can have multiple layers, meanings and justifications on spending time and resources on. I find short film harder narratively but they are a good way to test out ideas. I typically have used them in the past to test out camera work, narrative elements and check if I could make a film in a particular genre.

Why did you choose to make your first “feature”, A Touch of Vengeance, in black and white?

“When I was younger, I started by making really bad stop-motion animations on an old phone.”

I used quotes there because what I noticed about A Touch of Vengeance and Nothing Goes is they’re refreshingly terse—barely an hour, or even less for Vengeance. How much of that was a conscious choice?

Vengeance was less deliberate in that sense, but with Nothing Goes, I really focused on pacing in specific parts. As long as a scene hit the right beats and had a bit of rhythm, I was happy to cut it down—removing any pointless sections. Hopefully, the consistent speed gives the film a non-stop energy. My thought process was: if the average audience member is going to give the film a chance, I need to keep them as entertained as possible. Micro- to low-budget films often drag, and when that happens, most people just switch off. The first edit of Nothing Goes was around 70–80 minutes. For the final cut, I was ruthless. We cut about two full scenes—Alex first meeting Lexy after her lesson and Alex in the back of the car on his way to his final resting place—plus trimmed down a few others. Altogether, we shaved off around 15 to 20 minutes.

Nothing Goes was also strikingly bleak. Was that a conscious decision, or how did it come about?

It was definitely a conscious decision with the final scene/sequence being the original initial idea before combining it with a small script, which was the complete opposite genre to the ending I had. I wanted to make a film that was multiple genres—you don’t typically see films switch halfway through. The idea was that, based on the advertising, the typical viewer would expect a Skins-style coming-of-age story. But halfway through, it morphs into a nightmare thriller. It’s also a working-class representation of the perception of university life, contrasted with the harsh reality. It’s a dog-eat-dog world, even in the film industry. Re-entering “reality” after uni can feel brutal. In a way, it’s a kind of Peter Pan story.

What are the biggest lessons you’ve learned since you started?

I believe being organised and giving yourself enough time to plan determines how fast and smoothly a production runs. Nothing Goes is still my most organised shoot—we filmed everything in 15–16 back-to-back days. The whole project took 7 months to finish (from final draft screenplay to final edit), but that was mostly due to budget constraints. Realistically, a lot of the footage could’ve been edited alongside production, and the whole edit process could have been sped up.

Sheffield isn’t exactly Hollywood. What have you found to be the biggest challenge about making movies there?

Sheffield actually offers a lot in terms of locations, so there have been more opportunities than challenges in that respect. The main issue is funding—which is something most filmmakers, no matter where they are, struggle with. It’s the universal film-making problem.

Have you had any amusing experiences while filming?

We shot Nothing Goes in January and went to the beach, so all the water scenes were freezing. Me and Steven Wardle, who plays Peaches, had to swim in the sea for the montage. It was brutal but worth the shot. We needed to shoot in winter, though and create a fake reality to reflect the narrative. It should be cold, but in the moments, they are living this dream before reality hits.

What filmmakers—large or small budget—have inspired your work?

“I’ve always tried to do something different when it comes to genre and audience expectations.”

You recently wrapped production on your vampire feature, All You Do is Bleed. Can you tell us about that project?

Just before production started on Nothing Goes, I wrote All You Do Is Bleed, a vampire film. Once post-production finished on Nothing Goes, I really tried to get that project moving. All You Do is Bleed follows a 16-year-old secondary school student, Zoey, who comes home after being inflicted with vampirism on a school trip—setting in motion a chain of events that forever changes the people around her. The film is non-linear, jumping back and forth around a police investigation into Zoey’s disappearance. It explores Zoey’s life with her dad, James, in a single-parent household. James is always working, trying to keep a roof over their heads, but in doing so, he’s neglecting his kids. Zoey, meanwhile, is trying to figure herself out—rebelling at school, at home, and out with her mates.

That’s all I can say without giving away spoilers!

Where do you want to go next?

I’ve got a few screenplays and features in mind. I wouldn’t mind doing a sci-fi film, something similar to On the Silver Globe. But more realistically, Nothing Goes might be getting a revamp on a much larger scale sooner than the next “different” project.

What advice would you give to other budding filmmakers?

- If you don’t have many filming opportunities, make them yourself! I’ve done it, so I know others can too. But you need to be willing to sacrifice time if you want to make a better film.

- Don’t be afraid to let go of some crew responsibilities, either—the more people involved, the more you can focus on your core role. But above all, networking is key.

- If you want to work in the industry, focus on building connections. A lot of people say you have to work your way up from the bottom, but some of my peers who focused on networking have gotten much further than those who didn’t.

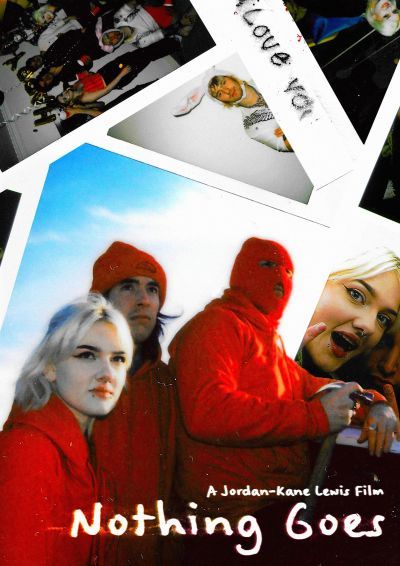

Nothing Goes (2023)

Rating: B

Dir: Jordan-Kane Lewis

Star: Aiden James, Katie Walker, Steven Wardle, Ian Hodson

“This guy I know, Andreas, used to work for these old criminal OGs. Basically, they’re retired now. But they still meet up at this pub at the edge of the Peak District: they still carry loads of cash and they’re still dealing. So the plan is, we’re going to go in, threaten them a little bit, take the cash, and leave.” Yeah. If ever something seemed like a really bad idea, that job offer would be it. Still, the combined power of pussy and desperation are hard to resist. Which is why vacationing uni student Alex (James), finds himself taking part in the above ill-conceived criminal enterprise, courtesy of girlfriend Lexy (Walker) and sketchy acquaintance Peach (Wardle).

Needless to say, this goes about as well as you would expect. However, along the way to an impressively bleak finish, there are diversions, so the outcome isn’t as simple as you’d expect. Initially, they look to have got away with their crimes, and the trio go on a holiday to Scotland. Which is where things start to go wrong, because Lexy might not be as committed to Alex, as he is to her. From there, it’s more or less downhill all the way, and after about half-way in, the sense of impending doom is quite palpable. Which is a shame, because the performance of James is easily enough to get your sympathy, despite being a layabout student. He’s still a nice guy, who simply wanted to help his aunt out of her money worries.

Of course, the road to hell is paved with good intentions, and Alex’s naivety – in a number of areas – proves to be a fatal character flaw. There’s a general sense of cynicism here, in that the characters can be divided into two categories: sheep and wolves. Or maybe three: sheep, wolves and hungrier wolves. If you’re a sheep, you’ll either be taken advantage of, or find yourself caught up in the problems caused by other woolly jumpers. It might take a while. They’ll still eat you in the end. Given this, you might make a case the film could be even shorter, with an early party scene, and footage of the vacation in Scotland, arguably superfluous towards that end, at the length here

Of course, the road to hell is paved with good intentions, and Alex’s naivety – in a number of areas – proves to be a fatal character flaw. There’s a general sense of cynicism here, in that the characters can be divided into two categories: sheep and wolves. Or maybe three: sheep, wolves and hungrier wolves. If you’re a sheep, you’ll either be taken advantage of, or find yourself caught up in the problems caused by other woolly jumpers. It might take a while. They’ll still eat you in the end. Given this, you might make a case the film could be even shorter, with an early party scene, and footage of the vacation in Scotland, arguably superfluous towards that end, at the length here

I was also expecting Alex’s film-making to be more significant than it ended up being. But there’s still plenty going on here, including some dangers I did not see coming. For it’s probably as effective a warning about the risks of thumbing a lift as The Hitcher – and that’s not the worst thing to befall Alex either. Given the likeable nature of the protagonist, I was pulling for him to find some way out of his increasingly perilous predicament. This consequently managed to keep my interest until the very end, which will drop like a ton of dirt on anyone who was pulling for a happy ending. Somewhat happy? Slightly happy? Don’t get your hopes up.

A Touch of Vengeance (2022)

Rating: C+

Dir: Jordan-Kane Lewis

Star: Paul Jonah, Leona Clarke, Martin Nadin, James Morton

When I hear the word “non-linear”, I reach for my gun. I’ve been burned by too many shitty Pulp Fiction wannabes, attempting to imitate a film which, frankly, is overrated to start with. Too often, jumbling a time-line is an effort to hide the flaws of a pedestrian plot from the audience. So reading the synopsis here – “An easy job takes a turn for the worse, making a hitman’s life more complicated in this nonlinear micro-budget film” – had me flicking the safety off. To my pleasant surprise, that aspect isn’t a problem. Yes, it’s not told in chronological order. However, it’s not hard to tell where it’s going, and to assemble the pieces appropriately.

When you do that, you’ll basically get a Northern England version of Léon: The Professional. You have hitman Lucas (Jonah), who doesn’t have much of a life outside his work. One day, he’s sent to clean up a double murder scene, perpetrated by Marcus (Nadin), the psychopathic son of his boss. Except, one of the victims, Maria (Clarke) isn’t dead, which poses Lucas with a bit of a problem. He ends up stashing her away in his apartment, while he tries to figure out what to do. But the longer he stays with her, the more his relationship with Matilda sorry, Maria gives him a reason to live. For obvious reasons, Marcus is of the opposite opinion, Maria representing a potentially dangerous loose end, in need of tidying up.

The parallels are apparent, from an opening scene where Lucas puts the fear of God into his target, before putting him on the phone with Lucas’s boss, then vanishing into the shadows. There’s even a scene where Lucas and Maria tend to his pot-plant. Clearly, it’s not going to hold a candle to Besson’s masterpiece, especially on the action front, where that micro-budget is most apparent. But I’m never going to hate a love-letter to a movie I also love. It’s not a slavish copy, and I liked some of the additions, such as Lucas’s visit to a body-disposal facility, run by a surprisingly chipper dude. The Derbyshire setting isn’t one we see often, and there’s some bone-dry humour coming out of the local characters.

The parallels are apparent, from an opening scene where Lucas puts the fear of God into his target, before putting him on the phone with Lucas’s boss, then vanishing into the shadows. There’s even a scene where Lucas and Maria tend to his pot-plant. Clearly, it’s not going to hold a candle to Besson’s masterpiece, especially on the action front, where that micro-budget is most apparent. But I’m never going to hate a love-letter to a movie I also love. It’s not a slavish copy, and I liked some of the additions, such as Lucas’s visit to a body-disposal facility, run by a surprisingly chipper dude. The Derbyshire setting isn’t one we see often, and there’s some bone-dry humour coming out of the local characters.

It’s shot in black-and-white, though I’m not sure about the purpose of that choice. There’s also occasional use of a strobing effect, which seems to have strayed in from a nineties music video, and should have been sent back there. At a brisk hour, there’s not a lot of fat on its bones, and consequently feels an appetizer rather than a main course. Certain elements do have scope for further development, most obviously the relationship between Lucas and Maria, which is more functional than particularly affecting. On the other hand, the non-linear structure is nowhere as chaotic as the poster suggests, and does provide a satisfying “ah-hah!” moment, when you realize both where this is going, and where it has gone.