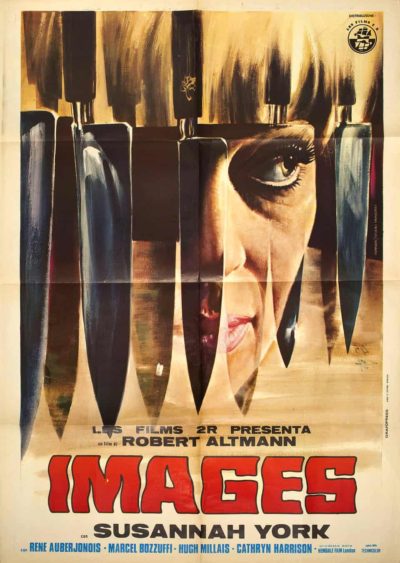

Rating: C

Dir: Robert Altman

Star: Susannah York, Rene Auberjonois, Marcel Bozzuffi, Hugh Millais

For the third time in eight days of this series, we are opening the box marked “A attractive young woman goes nuts for a male director,” and to be honest it’s getting a little stale. Though at least Robert Altman does not come with quite the same cultural baggage as Roman Polanski, responsible for both Repulsion and Rosemary’s Baby. He is instead among the most respected film-makers to try dipping his toe into the horror genre, having been Oscar-nominated on five occasions (more, for example, than Coppola or Kubrick). After his groundbreaking success of M*A*S*H, Altman had made revisionist Western McCabe & Mrs. Miller, which is regarded better now than at the time of release. He then opted to make a movie based on his own script, for the first time since Altman’s feature debut, 1957’s The Delinquents.

That said, it appears the story was more of an outline, with details filled in by the cast on set. This improvisational approach was certainly a part of Altman’s style, and in some ways ahead of its time. He said, “When I cast a film, most of my creative work is done. I have to be there to turn the switch on and give them encouragement as a father figure, but they do all the work.” I’m not sure how I feel about a director basically delegating the movie to the actors. Part of me thinks it’s kinda lazy – what is the job of a director, if not to mould the actors to his will? Yet on the other hand, I’m sure that certain actors appreciate the freedom, and the way film-making becomes more of a collaborative process. If you get the right players – that’s likely to what Altman refers in his quote – it will work well.

It’s not something you see often in horror though; at least, outside of the dreaded “found footage” sub-genre. While occasional moments may be improvised, horror tends to be considerably more structured, almost out of necessity. However, if there’s another sub-genre where it can work, the “attractive young woman goes nuts” one is probably a good candidate, being more reliant on atmosphere and feeling, rather than a structured story. This focuses on Cathryn (York), a children’s author who is experiencing apparent hallucinations, both auditory and visual, e.g. taunting phone-calls saying her husband is having an affair. Her spouse, Hugh (Auberjonois), decides to get them both out of the city, to a peaceful cottage deep in the Irish countryside. Needless to say, it doesn’t help much.

It’s not something you see often in horror though; at least, outside of the dreaded “found footage” sub-genre. While occasional moments may be improvised, horror tends to be considerably more structured, almost out of necessity. However, if there’s another sub-genre where it can work, the “attractive young woman goes nuts” one is probably a good candidate, being more reliant on atmosphere and feeling, rather than a structured story. This focuses on Cathryn (York), a children’s author who is experiencing apparent hallucinations, both auditory and visual, e.g. taunting phone-calls saying her husband is having an affair. Her spouse, Hugh (Auberjonois), decides to get them both out of the city, to a peaceful cottage deep in the Irish countryside. Needless to say, it doesn’t help much.

Indeed, it seems to exacerbate Cathryn’s problems, as she’s literally haunted by visions of a previous dead lover, Rene (Bozzuffi). Another ex-lover – she seems to have put herself about a bit! – genuinely turns up, in the shape of Marcel (Millais), along with his teen daughter, Susannah (Cathryn Harrison, the granddaughter of Sir Rex). Cathryn sees an apparent copy of herself in the nearby countryside, and her mental illness takes an increasingly violent turn, blasting Rene with a shotgun and stabbing Marcel to death. Or does she? It’s quickly apparent that she is a very unreliable narrator, and much of what Cathryn experiences has little or no basis in reality. [Adding to the general air of confusion, the characters all take their names from other actors in the film]

What it shares with Rosemary’s Baby is a heroine who has precious little agency. No-one asks Cathryn, for example, whether or not she wants to go to the remote Irish countryside. Hugh decides that’s what is best, and the next thing we see, they are in the car. Going by the way they treat her, Rene and Marcel both see Cathryn as little more than meat: there’s a recurring motif of hunting and dead animals, that may be an allegory for this. Susannah is about the only person who treats her as an equal, and she’s still a minor. She does seem to look up to Cathryn, asking her “Will you be my best friend?” and then says, “When I grow up, I’m going to be exactly like you.” Be careful what you wish for, little girl.

Though Altman is American, this feels specifically British, perhaps fitting in to the “rural horror” theme, common in the first part of the decade. In this, city-dwellers head out to what they imagine will be an idyll in the countryside, only to find – for one reason or another – the reality is considerably less than paradise. The Wicker Man, which we’ll get to tomorrow, is an obvious example. Straw Dogs also falls into that category, and is explicitly invoked by the video sleeve. Here, though, the journey is more an attempt to run away from a threat that’s already present, and only ends up being brought along with the protagonists. The cinematography of regular Altman collaborator Vilmos Zsigmond makes the landscape seem more beautiful than a threat (above), though John Williams’s Oscar nominated score does add to the creepiness, amped up by his collaboration with Japanese musician Stomu Yamash’ta. It is definitely one of his less tuneful.

Though Altman is American, this feels specifically British, perhaps fitting in to the “rural horror” theme, common in the first part of the decade. In this, city-dwellers head out to what they imagine will be an idyll in the countryside, only to find – for one reason or another – the reality is considerably less than paradise. The Wicker Man, which we’ll get to tomorrow, is an obvious example. Straw Dogs also falls into that category, and is explicitly invoked by the video sleeve. Here, though, the journey is more an attempt to run away from a threat that’s already present, and only ends up being brought along with the protagonists. The cinematography of regular Altman collaborator Vilmos Zsigmond makes the landscape seem more beautiful than a threat (above), though John Williams’s Oscar nominated score does add to the creepiness, amped up by his collaboration with Japanese musician Stomu Yamash’ta. It is definitely one of his less tuneful.

In the end though, it feels too much like we’ve seen all this before, despite a reasonably strong performance from York. Not only was this Altman’s sole attempt at horror, it feels as if he hadn’t actually seen too many genre entries, causing him to trot out a lot of very familiar tropes. We’re just watching someone fall apart for the sake of it, and for those whose sanity is on more solid ground, this kind of thing will elicit sympathetic pity instead of fear. There’s not even much sense of loss for the audience, since we never see a “sane” Cathryn: her descent into madness is already well under way by the opening scene. To be honest, once you realize what’s happening, the film doesn’t have much more to offer, and I prefer Polanski’s take on similar subject matter. If I’d seen this first, however, my opinion might well be different.

This article is part of our October 2022 feature, 31 Days of Classic Horror.