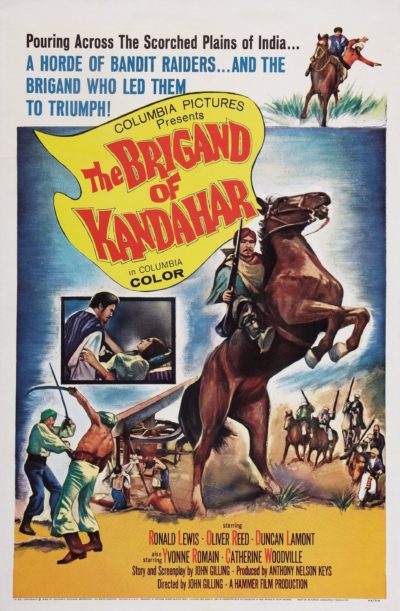

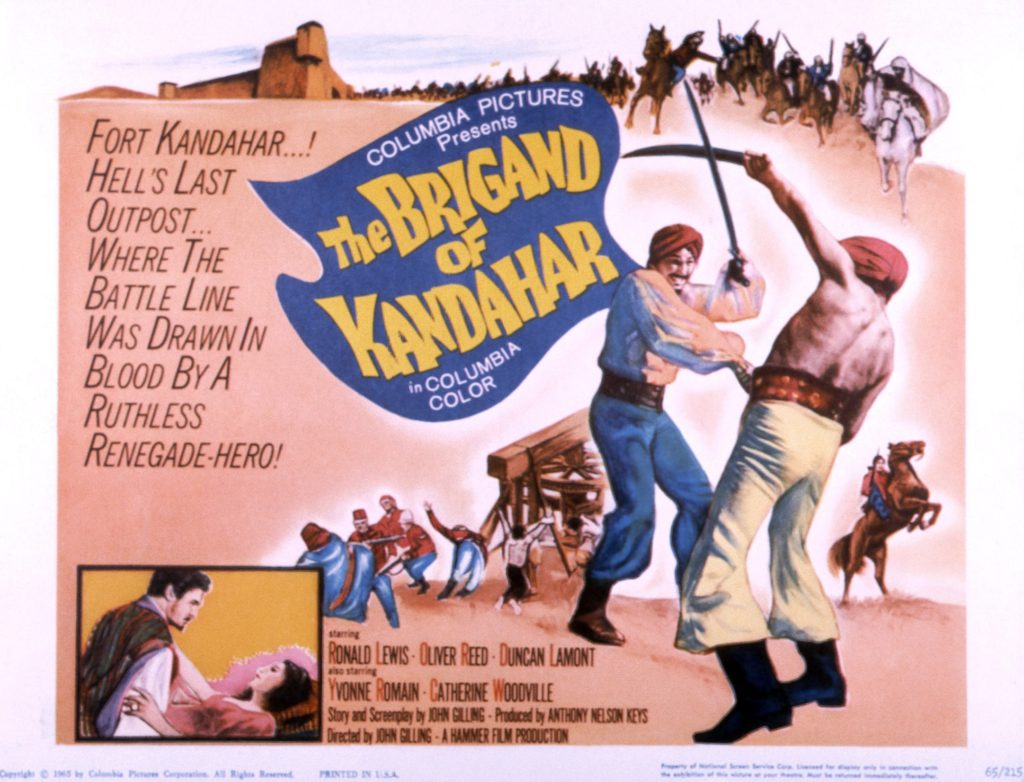

Rating: C-

Dir: John Gilling

Star: Ronald Lewis, Oliver Reed, Glyn Houston, Yvonne Romain

Released the same year as the big-budget feature which was She, this is another historical entry – specifically, 1850’s India. However, unlike She, this production had entirely to make do with the South of England as a stand-in for its exotic settings. This does not appear to have come any closer to India than perhaps a take-out curry for the crew. Indeed, even the larger-scale shots of battle, were largely borrowed footage, taken from 1956 Victor Mature feature Zarak, on which Gilling was assistant director – occasionally with the cast here superimposed on it, in unconvincing fashion. There’s nothing at all like the sense of spectacle which She occasionally was able to provoke.

In one way though, it’s interesting and one could say, almost revolutionary; in focusing on mixed-race British officer Lt Case (Lewis). He is unjustly court-martialled for cowardice, in part due to having an affair with Elsa (Katherine Woodville), the wife of a colleague. Case is not only drummed out of the Bengal Lancers, he is sentenced to ten years in a military gaol. With local help, he escapes and heads into the mountains, to become one of a gang of bandits, under the leadership of British-educated Afghani Eli Khan (Reed). Khan agrees to protect Case, if he trains soldiers to attack the Empire garrison. While Case wants revenge on his commanding officer, Colonel Drewe, it’s a goal which causes a crisis of conscience for the former soldier, who is caught between the two halves of his identity

Of course, all the progressive spirit this could have had, is undone by an almost entirely Caucasian cast, led by Lewis and Reed in blatant brownface. This has not aged well, and the film manages the impressive feat of, from the standpoint of a modern viewer, being both staunchly anti-imperialist and incredibly racist. I did find myself distracted by the realization that there was, presumably, a make-up artist responsible for touching-up Yvonne Romain’s cleavage, and keeping it the appropriate shade of brown, in her role as Ali Khan’s sister, Ratina. The job reminds of the joke from What’s New Pussycat, where Woody Allen explains, “I got something at the striptease. I help the girls dress and undress… Twenty francs a week.” When someone says that’s not very much, Allen replies, “It’s all I can afford.”

There’s an awkward lack of moral centre to the film. Case is, after all, an unrepentant adulterer, who betrays his country (albeit only after it has betrayed him, admittedly). The script seems to realize this, half-way through, suddenly injecting a new character. This is British journalist James Marriott (Houston), who is roaming the Northwest frontier, reporting for his newspaper. He smells a story in Case’s court-martial and subsequent defection. Fate conveniently brings him into Case’s realm, after Marriott is captured while accompanying a patrol. The writer is released in order to tell Drewe that Case guarantees safe passage to civilians leaving Kandahar. But with Khan on a diplomatic mission to another tribe, Ratina over-rules Case, killing most of the departing civilians bar Marriott and Elsa.

I was expecting there to be considerably more jealousy between Elsa and Ratina for the favors of Case. But this angle seems curiously underplayed. Sure, the issue of what to do with Elsa is what leads to the final confrontation between Case and Khan. But she has clearly moved on, having been told by Marriott of Case’s role in her husband’s death (another reason why he cannot be the hero here). Instead, she sneaks out while Case and Khan are brawling, and returns to the fort with Marriott. Then follows the inevitable battle between British and brigands – though as noted above, it’s largely recycled footage. The movie ends with a surprisingly impassioned speech by Marriott to Drewe, after he’s asked what his memory will be of Fort Kandahar; it’s worth repeating in its entirety.

Just the memory of one man. A man whom l saw destroyed, piece by piece. A man who served his regiment well, but had the audacity to believe that his allegiance would be recognised. Especially by his commanding officer. A man who had the temerity to love, but committed the sin of being discovered, and whose shade of skin set the seal on his betrayal.

Oh, it’s all right, Colonel, l shan’t be sending that story to my paper. In fact, I shan’t be writing about you at all. I shall write about the brave men who serve under you. The men who think that you are great, who trust you. The men who fight for what they believe is right, and who will carry the flag as long as they are alive to breathe the free air. That’s something worth writing about, don’t you think?

If only the film hadn’t waited until the very end before showing such forthright honesty and the courage of its convictions.

The movie was a “last hurrah” in a number of ways. Perhaps most importantly, it was the final Hammer film made as a co-production between them and their American partners, Columbia Picturs. It was also the last time Lewis and Reed, both regularly used by the studio in the first half of the decade, would appear for Hammer. Reed later called Brigand the worst film he made for them… and he may have a point. Among his major roles, I’d call it a toss-up between this and The Pirates of Blood River. The two actors’ careers subsequently would follow diverging paths. Lewis found it increasingly hard to get work, and committed suicide by overdose in 1982. On the other hand, the year Brigand was released also saw Reed work with Ken Russell for the first time, and he’d become a global star shortly after, for playing Bill Sikes in Oliver!

The movie was a “last hurrah” in a number of ways. Perhaps most importantly, it was the final Hammer film made as a co-production between them and their American partners, Columbia Picturs. It was also the last time Lewis and Reed, both regularly used by the studio in the first half of the decade, would appear for Hammer. Reed later called Brigand the worst film he made for them… and he may have a point. Among his major roles, I’d call it a toss-up between this and The Pirates of Blood River. The two actors’ careers subsequently would follow diverging paths. Lewis found it increasingly hard to get work, and committed suicide by overdose in 1982. On the other hand, the year Brigand was released also saw Reed work with Ken Russell for the first time, and he’d become a global star shortly after, for playing Bill Sikes in Oliver!

This is a film which seems relatively forgotten in the Hammer filmography, and considerably less-discussed. This may be partly because of the brownface, but to be honest, it doesn’t do enough with its elements to be well remembered. It’s definitely a case where it was too ambitious for the available resources, and the results (much like Romain’s painted cleavage) prove a bit of a distraction from the plot and characters. Though given the weaknesses in both, that may not be a bad thing. Rather than “Never fight a land war in Asia”, about the only useful lesson to be learned here is, never have an adulterous affair with a fellow officer’s wife in Asia.

This review is part of Hammer Time, our series covering Hammer Films from 1955-1979.