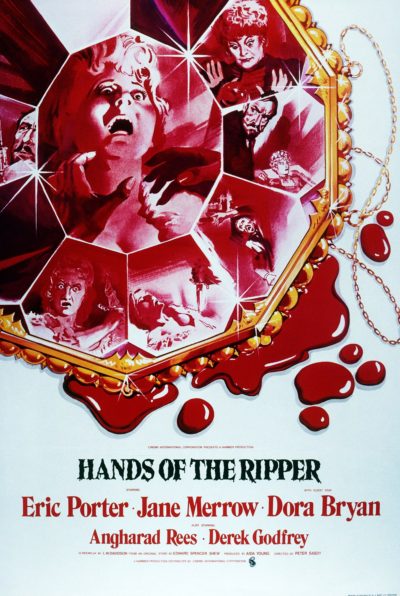

Rating: B

Dir: Peter Sasdy

Star: Angharad Rees, Eric Porter, Jane Merrow, Keith Bell

If ever there were a Hammer movie that should have found a spot for Michael Ripper, it was surely this one. Sadly that was not to be, yet there’s still a good deal here to appreciate. It manages to do a better job of evoking psychological horror than most of the Jimmy Sangster-scripted efforts. And while the later wave of Hammer helmers didn’t include anyone with quite the directorial skill of Terence Fisher, Sasdy might be the most talented. In both this and Countess Dracula, he showed a talent that led to quality product, a cut above some of their seventies work (and I’m higher on that decade than many). In particular, both films contain a sympathetic and complex portrayal of female villains, not something seen often in the studio’s output.

Here, it may be the closest British cinema of the time came to making a giallo film, though other elements make it almost like a proto-slasher movie. It’s certainly among the goriest of Hammer’s productions. Per Wikipedia, “Gialli are noted for psychological themes of madness, alienation, sexuality, and paranoia… Giallo killers are almost always motivated by insanity caused by some past psychological trauma.” That’s exactly what we have here. Anna (Rees) is the daughter of Jack the Ripper, and as a very young child, watched him kill her mother after Mum discovered Dad’s secret. Fifteen years later, she’s the assistant to a fake medium (Dora Bryan, in a lovely if brief role). But a specific double-whammy of events – a sparkling light and a kiss on the cheek – trigger a psychotic episode. Foster mom gets impaled with a poker, and Anna is found in the corner, with no memory of events.

Nobody believes a little slip of a girl could have done it, so she’s allowed to go home with Dr. Pritchard (Porter). He knows the truth and, as a student of Freud, wants to study the young woman and find out what makes her kill. Apparently, in the early 20th century, you could just go to prison, pick out a teenage girl and bring her home to live with you. Massive red flags abound, such as Dr. Pritchard putting Anna in both his late wife’s chambers and clothes. Indeed, given the scenario and setting, there were points where I found myself wishing for a Hands of the Ripper/My Fair Lady crossover. Eliza Doolittle stalking the East End and stabbing whores in the face with hat-pins, while singing Just You Wait? Yes, please.

Nobody believes a little slip of a girl could have done it, so she’s allowed to go home with Dr. Pritchard (Porter). He knows the truth and, as a student of Freud, wants to study the young woman and find out what makes her kill. Apparently, in the early 20th century, you could just go to prison, pick out a teenage girl and bring her home to live with you. Massive red flags abound, such as Dr. Pritchard putting Anna in both his late wife’s chambers and clothes. Indeed, given the scenario and setting, there were points where I found myself wishing for a Hands of the Ripper/My Fair Lady crossover. Eliza Doolittle stalking the East End and stabbing whores in the face with hat-pins, while singing Just You Wait? Yes, please.

The problem is, her murderous outburst wasn’t a one-off. Any time the two elements occur, someone is going to die. Maybe a servant; maybe a convenient prostitute who shares a name with one of her father’s victims; maybe a royal medium who delves into Anna’s past. Interestingly, the last named’s reaction to “seeing” the Ripper in her vision suggests a person of some renown – perhaps Prince Albert Victor, Queen Victoria’s grandson, who has been suspected. The final threat is aimed at Dr. Pritchard’s son (Bell, looking a ringer for Edgar Allen Poe) – or more specifically, his blind fiancée (Merrow), who takes Anna to the Whispering Gallery in St. Paul’s Cathedral. As soon as they announce the number of steps up to it, you know someone will be toppling all the way back down.

There’s a slew of familiar faces here. Rees would play Demelza in the late seventies version of Poldark. But the minor roles have some names of note as well. Perhaps most notably, Long Liz, the hat-pinned prostitute, is Lynda Baron. She’d go on to play Nurse Gladys Emmanuel, the object of Ronnie Baker’s desire in classic sit-com Open All Hours. Dr. Pritchard’s maid, Dolly, was Marjie Lawrence. She spoke the first words uttered on ITV, and was the mother of TV presenter, Sarah Greene. Finally, another maid – that of royal medium, Madame Bullard – is Molly Weir, who was Hazel McWitch, in Rentaghost, and also had a long-running series of adverts in the seventies for cleaner. Need I say more than, “Flash – cleans baths without scratching”? OK, anyone under the age of fifty is probably glazing over about now. I’ll move on.

The production values here are a cut above, the period atmosphere being enhanced by Sasdy being able to use the Baker Street set built for The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes, filmed previously at Pinewood. However, Hammer weren’t able to get permission to shoot inside St. Paul’s, and had to reconstruct the interior for their finale on set. The film also makes good use of music. The main theme, composed by Christopher Gunning, sounds almost like a riff on Erik Satie’s Gymnopédie No.1. Its soothing tones are in sharp contrast to the set-pieces here; more befitting to an advert for chocolates, than a psycho slasher pic. The peak, however, is in the finale, where a choir sings, almost in the background, as event reach their tragic conclusion. It’s one time where Hammer’s fondness for abrupt endings, really works for them.

The production values here are a cut above, the period atmosphere being enhanced by Sasdy being able to use the Baker Street set built for The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes, filmed previously at Pinewood. However, Hammer weren’t able to get permission to shoot inside St. Paul’s, and had to reconstruct the interior for their finale on set. The film also makes good use of music. The main theme, composed by Christopher Gunning, sounds almost like a riff on Erik Satie’s Gymnopédie No.1. Its soothing tones are in sharp contrast to the set-pieces here; more befitting to an advert for chocolates, than a psycho slasher pic. The peak, however, is in the finale, where a choir sings, almost in the background, as event reach their tragic conclusion. It’s one time where Hammer’s fondness for abrupt endings, really works for them.

It’s never entirely clear whether Anna is actually possessed by her father’s spirit in some manner, or if it is the trauma-induced psychosis Pritchard believes. I’m leaning towards the former, given the way her hands get his syphilitic sores when she enters berserk mode. Though I do note the way in which Pritchard is penetrated by a distinctly Freudian sword towards the end. Read into that what you will. Though you may be too busy wincing, since he has to yank it out of his innards with the air of a convenient door-handle. Well played, Mr. Sasdy. Well played…

The performances are very solid, though you do have to question Pritchard’s willingness to overlook not one, but multiple, murders by his young charge. I mean, our daughter had her legal moments, but underage drinking is a bit different from slashing someone’s throat with a broken hand-mirror (top). In terms of an innocent who kills without being consciously evil, this reminded me a bit of The Gorgon. Certainly, it stands as a counterpoint to Countess Dracula, which had a woman much more in control of her own agency, and Rees’s performance is considerably more sympathetic than Pitt. They’re just as good – I fractionally prefer Countess, though you really can’t go wrong with either.

This review is part of Hammer Time, our series covering Hammer Films from 1955-1979.