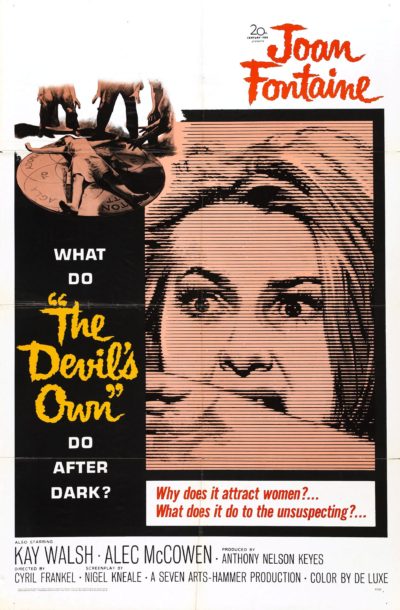

Rating: C-

Dir: Cyril Frankel

Star: Joan Fontaine, Kay Walsh, Alec McCowen, Ingrid Brett

a.k.a. The Devil’s Own

And it was going so well, too… Okay, maybe not so well. But this less well-known Hammer feature was playing like a rural England predecessor of The Wicker Man, and achieving a nicely understated sense of occult menace. Then it blew it all with a finale of spectacular incompetence. Let’s not get ahead of ourselves though. This marked writer Nigel Kneale’s return to the Hammer fold. It had been close to a decade since his last script for the company was made, 1957’s The Abominable Snowman. He had been busy on other projects, and had even turned down an offer from producer Harry Saltzman to adapt Ian Fleming’s James Bond novels for the big screen.

This was not an original Kneale story, however, being an adaptation of a 1960 book, The Devil’s Own (the title used for the film in America), written by Norah Lofts under the pseudonym of Peter Curtis. Kneale had been working on the screenplay since soon after the book was published, but it had taken several years for it to reach the screen. Notably, he added an element of class conflict which wasn’t apparently present in the original novel. Otherwise, it seems to have been a relatively faithful adaptation, though Kneale was reportedly unhappy with changes made by Hammer. He wanted to poke fun at the idea of an English coven, but those elements were removed in the finished film.

Heroine Gwen Mayfield (Fontaine) is a teacher, recently returned from a post in Africa, which ended in a native revolt and a nervous breakdown. She obtains a post as head teacher in the small village of Heddaby, thanks to brother and sister Alan and Stephanie Bax (McCowen and Walsh). Initially, it seems just like the tranquil position she needs, despite Alan’s odd quirk, of dressing up like a vicar, even though he flunked out of his religious training. But a spat over pupil Linda Rigg (Brett) and her boyfriend Ronnie Dowsett, whose families don’t get along, peels back the thin veneer of nice cups of tea and civility. There is something rotten in the state of Haddaby. Could it be… Satan? Given pagan religion was a major factor in Gwen’s earlier mental meltdown, it’s no surprise when she has a relapse, losing her memory, just as she was about to expose a suspicious death.

Heroine Gwen Mayfield (Fontaine) is a teacher, recently returned from a post in Africa, which ended in a native revolt and a nervous breakdown. She obtains a post as head teacher in the small village of Heddaby, thanks to brother and sister Alan and Stephanie Bax (McCowen and Walsh). Initially, it seems just like the tranquil position she needs, despite Alan’s odd quirk, of dressing up like a vicar, even though he flunked out of his religious training. But a spat over pupil Linda Rigg (Brett) and her boyfriend Ronnie Dowsett, whose families don’t get along, peels back the thin veneer of nice cups of tea and civility. There is something rotten in the state of Haddaby. Could it be… Satan? Given pagan religion was a major factor in Gwen’s earlier mental meltdown, it’s no surprise when she has a relapse, losing her memory, just as she was about to expose a suspicious death.

[Spoilers follow] And that’s where things start to fall apart. To this point Kneale has done a good job of hinting at the darkness lying just below the suburban surface, where petty jealousies get inflamed and trigger excessive reactions. But, as ever, amnesia necessary to the plot is a weak device. And things only get worse after Gwen remembers what happened – being triggered by seeing a girl playing with a doll – and returns to Haddaby. It turns out Stephanie isn’t the hard-headed writer she appeared to be, but is the leader of a coven of witches. They are preparing to sacrifice Linda, to give Stephanie a “second life” , and on her return, bring Gwen in as one of their number. Never mind that this makes no sense, since the last time they saw her, she was about to blow the whistle on them.

This is basically Evil Overlord 1.0.1. I mean, Stephanie literally says to Gwen, “And now that you’re one of us, I can tell you everything.” Which she does, including getting Gwen to read out loud the instructions for the evening’s ritual. Conveniently, these include a stern warning on what not to do. “Until the very moment of sacrifice, let all be kept pure. Let no single drop of blood be spilled in that place, nor other defilement, neither human nor any beast so ever, lest the whole dread power do turn against the seeker and destroy him utterly.” It couldn’t be any less subtle, if it had been preceded by sirens, and a flashing intertitle card reading, “IMPORTANT PLOT POINT”.

If I’d been making the film, I might have had Ronnie separate Linda from her purity, though since she’s only fourteen, that might have been a bit suspect. Instead, Gwen does the obvious, and waits for the climactic moment of the ceremony before grabbing the dagger and cutting herself, helpfully reminding the audience by yelling, “At the moment of sacrifice, let no blood be spilled!” I almost fell out of my chair at this point – though not because of the suspense or shock inherent in the scene, because there isn’t any. No, it was because that line was sampled in the My Life With The Thrill Kill Kult song, On This Rack. It only took me thirty-two years to discover the original source of the sentence.

To get to that point, however, you have to get through perhaps the most embarrassing scene in Hammer history. The ceremony consists of what can only be called an interpretive dance routine, overseen by Stephanie, with a candelabra on her head, while caveman-style music is made in the background. Perhaps this element was left over from Kneale’s piss-take of English Satanism, and no-one realized it was part of the joke? As we’ll see down the road, Hammer always seemed to have this problem with their witchcraft films. They could never seem to figure out how to deliver a fitting climax and resolution.

There are some positives, and this can be seen as an early example of “folk horror”. Kneale’s script makes some effort to provide a modern explanation for the occult. Stephanie says, “Call it a power or a force that we are going to release. Perhaps it’s in yourself – something in you… You could touch an H bomb and say, ‘l know what’s in there, uranium and stuff… that is all.’ But when it is triggered off… This is a trigger mechanism, too.” There is one genuinely creepy moment, when Gwen is exploring the coven’s lair and comes across a pentagram containing a sack inside which something is… writhing. The contents are not happy. [Though admittedly, less so than the dead rabbit, graphically skinned by a cheery butcher earlier on]

The supporting cast is a who’s who of seventies sit-com talent. Rudolph Walker from infamous show Love Thy Neighbour, supposedly has an uncredited role as one of the Africans at the beginning (though the IMDb gives two actors credit for the same character), and Michelle Dotrice, later to be Michael Crawford’s wife in Some Mothers Do ‘Ave ‘Em, plays Gwen’s housekeeper. But the cherry here is the presence of sitcom legend Leonard Rossiter as Dr. Wallis, who takes care of Gwen after her second breakdown. It is a bit of a problem, because his iconic performances in Rising Damp and as Reginald Perrin, make it difficult to take him in a serious role. [See also: 2001: A Space Odyssey] It’s also unfortunate his appearance coincides with the script’s sharp turn into idiocy.

The film’s lack of commercial success is entirely understandable – never a good idea to leave the audience thoroughly disappointed, regardless of the merits to that point. It marked a sad end for Fontaine’s movie career, which had included an Oscar in 1942 for Suspicion, and two further nominations.

This review is part of Hammer Time, our series covering Hammer Films from 1955-1979.