Rating: C

Dir: Val Guest

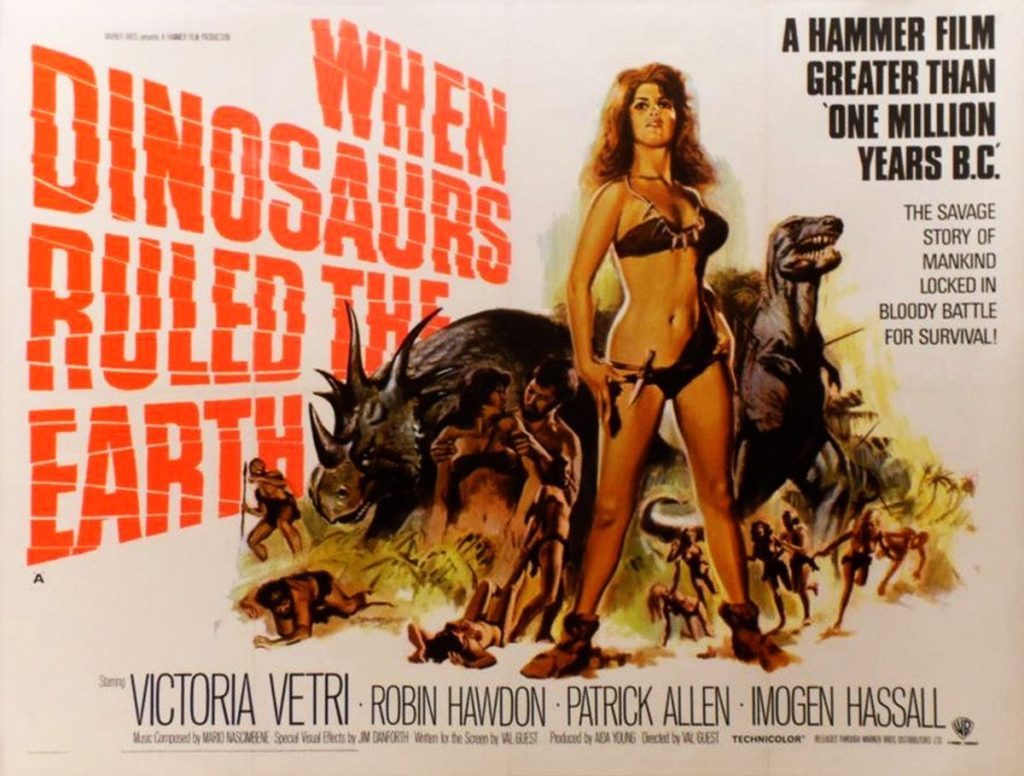

Star: Victoria Vetri, Robin Hawdon, Imogen Hassall, Patrick Allen

“Go big or go home”, they say. And, in terms of historical inaccuracies, this chooses the former. One Million Years B.C. may have played fast and loose with archeology, but there were only a hundred million years or so separating the humans and dinosaurs which cohabited in the movie. This, however, opens with a Patrick Allen monologue which concludes this takes place in “A time when there was as yet no moon.” Wait, what? The scientific consensus is the moon formed about 4.5 billion years before semi-civilized man showed up. Though, actually, the cataclysmic lunar creative process vaguely described here, only became accepted after the film’s release. So, I guess credit either to writer/director Guest, or the man who wrote the treatment, J.G. Ballard.

Yes, you read that right. The man responsible for Crash and The Atrocity Exhibition (the latter collection including his gloriously named story, “The assassination of John Fitzgerald Kennedy considered as a downhill motor race”), was involved in a film perhaps best described as One Million and One Years B.C. Or, perhaps, 4.5 Billion Years B.C. According to Ballard, Hammer producer Aida Young was a fan of his post-apocalyptic novel The Drowned World, and brought him in to pitch to Anthony Hinds. Ballard’s idea of showing a tidal wave receding got him the gig, though how much more from Ballard made it on-screen is doubtful. He later said, “many of the basic elements and the overall storyline are mine, and much of the detailed narrative is [Gusst’s].” What’s notable, is the opening credits manage to misspell his name, calling him J.B. Ballard.

Maybe that’s why he later reportedly called it, “without a doubt, the worst film ever made”. Like almost all such claims, it’s not the case. Indeed, this is the only Hammer movie ever Oscar-nominated. The effects of Jim Dankworth and Roger Dicken were honoured at the 1972 Academy Awards, but lost out to Bedknobs and Broomsticks, which did have more than 10 times the budget. They are good. Some may consider this blaspheny – technically perhaps even better than Ray Harryhausen’s in B.C. Though they don’t generally capture quite the same sense of life, and it’s harder to forget you’re watching stop-motion. The other obvious point of comparison are the two films’ busty blonde starlets. Vetri, under the name of “Angela Dorian”, was the Playboy Playmate of the Year in 1968, which is as good an excuse as any, to link to this picture.

Maybe that’s why he later reportedly called it, “without a doubt, the worst film ever made”. Like almost all such claims, it’s not the case. Indeed, this is the only Hammer movie ever Oscar-nominated. The effects of Jim Dankworth and Roger Dicken were honoured at the 1972 Academy Awards, but lost out to Bedknobs and Broomsticks, which did have more than 10 times the budget. They are good. Some may consider this blaspheny – technically perhaps even better than Ray Harryhausen’s in B.C. Though they don’t generally capture quite the same sense of life, and it’s harder to forget you’re watching stop-motion. The other obvious point of comparison are the two films’ busty blonde starlets. Vetri, under the name of “Angela Dorian”, was the Playboy Playmate of the Year in 1968, which is as good an excuse as any, to link to this picture.

Vetri has had an interesting life, if accounts are to be believed. One of her Playboy pics went to the moon, inserted into documentation for Apollo 12 astronaut Pete Conrad as a joke by NASA ground staff. As Dorian, she had a small role in Roman Polanski’s Rosemary’s Baby, where Mia Farrow tells her, “I’m sorry. I thought you were Victoria Vetri, the actress.” She was friends with Sharon Tate; indeed, she was invited to Tate’s house the night the Manson family came to visit. She called off because Vetri felt sick, and after subsequent events, Polanski then gave her a Glock 9mm for protection. Over 40 years later, the actress supposedly used it to shoot her fourth husband, Bruce Rathgeb, after an argument in 2011. She spent almost seven years in prison for that, being released in 2018 at the age of 73.

All of which is probably more interesting than the film, which feels almost like a reboot of B.C. rather than its own entity. Blonde switches tribes, roams around the Canary Islands with or without her boyfriend for a bit; jealousy and cat-fights; dinosaur sequences; largely unintelligible dialogue in Cave-lish; everything ends in a sudden natural disaster (the tidal wave, rather than a volcano). Aside from a few seconds of nudity here, courtesy of Vetri’s character Sanna skinny-dipping, there’s not much to distinguish the two films. But in terms of screen presence, Vetri falls short of Raquel Welch. Not that many male viewers may notice, considering her costume is even more skimpy, and appears held up entirely by the willpower of the censor.

The only original idea comes in the middle, during Sanna’s wanderings about. During a storm, she takes shelter inside the remnants of a giant, recently-hatched egg. The next morning, the egg next to it has also hatched, and the adorable giant lizard which emerged, imprints itself on Sanna. Even more amusingly, when the Mom-osaur returns, she too regards the blonde human as part of her litter, casually nudging a whole deer she brought back in her direction as a breakfast suggestion. Sanna and the Kid-osaur end up bonding in a way that’s quite adorable, and actually serves a later plot purpose. Does make you wonder who the target audience is though. It’s the kind of thing calculated to excite eleven-year-old boys everywhere, while Vetri… would excite a slightly older demographic, shall we say. Probably explains why, in the US, this had the nudity cut and went out with a “G” rating. Likely confusing those eleven-year-olds terribly.

The only original idea comes in the middle, during Sanna’s wanderings about. During a storm, she takes shelter inside the remnants of a giant, recently-hatched egg. The next morning, the egg next to it has also hatched, and the adorable giant lizard which emerged, imprints itself on Sanna. Even more amusingly, when the Mom-osaur returns, she too regards the blonde human as part of her litter, casually nudging a whole deer she brought back in her direction as a breakfast suggestion. Sanna and the Kid-osaur end up bonding in a way that’s quite adorable, and actually serves a later plot purpose. Does make you wonder who the target audience is though. It’s the kind of thing calculated to excite eleven-year-old boys everywhere, while Vetri… would excite a slightly older demographic, shall we say. Probably explains why, in the US, this had the nudity cut and went out with a “G” rating. Likely confusing those eleven-year-olds terribly.

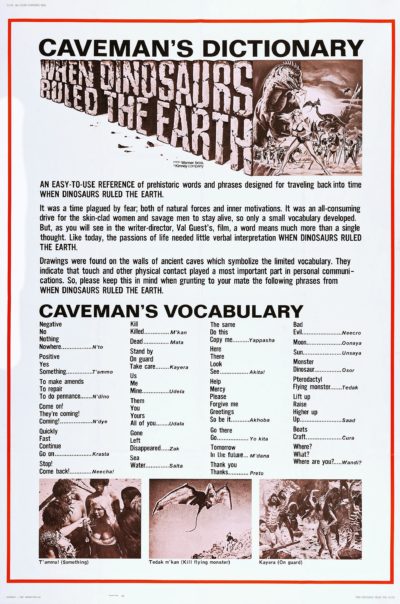

It’s probably reasonable enough for Hammer to have gone back to the well of one of their most successful pictures. Doing so four years later is a reasonable time-frame for the audience to be hungry for more dino-totty action. [Even if the delay was less due to audience considerations, and mostly due to the special effects not being ready. From Ballard’s original pitch to release took a solid three years] Me, though? It has only been three months since I watched Welch amble her away across the beach, and as mentioned above, this largely comes off a competent, yet underwhelming copy. Like The Vengeance of She, it feels as if Hammer were mockbustering themselves. This isn’t as bad as Vengeance. If you’d flipped this and B.C. round, then Welch would have seemed as much a knock-off. But I’ll keep watching. Maybe, just as narconovelas have improved my knowledge of Spanish, perhaps if I watch enough of these, I’ll eventually be able to speak fluent Caveman.

This review is part of Hammer Time, our series covering Hammer Films from 1955-1979.