Rating: C+

Dir: Robert Aldrich

Star: Jack Palance, Jeff Chandler, Martine Carol, Robert Cornthwaite

a.k.a. The Phoenix

I did not realize that Aldrich, who would go on to make The Dirty Dozen, directed a film for Hammer. Technically, this was a co-production between Hammer and German studio UFA, with United Artists also contributing. Aldrich was, however, in need of something to do. He had been fired by Columbia Pictures from The Garment Jungle: having signed a two-picture deal with them, he was basically in limbo for a bit, and effectively blacklisted by the Hollywood studios. Hammer made him an offer to come across to Europe and direct this for them, but the production was apparently a troubled one. Aldrich shot far more film than expected and reportedly punched producer Michael Carreras. He lost final cut, and the slashing of what was supposedly a three-hour film down to 83 minutes perhaps explains some of the movie’s problems. It works perfectly fine in chunks, but as a coherent entity, leaves quite a lot to be desired.

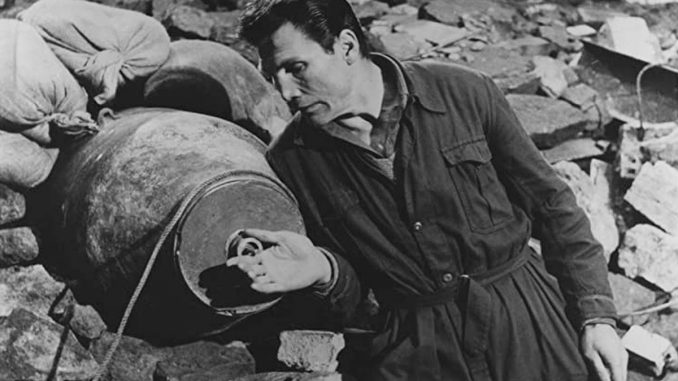

The story is set just after the end of World War II. Six war-weary German bomb disposal officers return to Berlin, and accept employment in the Allied sector, defusing the vast quantity of unexploded ordinance lying around. The men join in a death pool: half their wages will go into it, to be divided among whoever survives the next three months. It’s not long before numbers are getting thinned, not least because of the evil entity of a British thousand-pound bomb, which the team discover, at great cost, can not be made safe by their usual methods. The team eventually dwindles until the six men become two. In the blue corner, Eric Koertner (Palance): a former architect and whose idealism got him into trouble with the Nazis when he spoke out against them. In the red, Karl Wirtz (Chandler): an avowed cynic, whose golden rule involves looking after number one. Oh, and both have their eye on landlady and occasional black-market dealer, Margot Hofer (Carol, occupying the traditional Hammer role of Euroslut).

The wholesale cutting down of the film probably explains the painfully clunky voice-over which bookends the film. The beginning is particularly harsh, an awful example of what happens when you tell rather than show. It introduces us to the six men, in a way which seems more like notes from a casting call than anything: “Globke, the boy, who somehow through it all, had held on to fragments of his youth and innocence. Tillig, who asked for little, except the chance to laugh again.” Mind you, outside of Koertner and Wirtz, they might as well be cardboard. In this version at least, we learn next to nothing about the others, before they get blown up. Franz Loeffler (Cornthwaite) is kind to animals. That’s the level of character building we see here, and their deaths have little or no impact as a result.

The wholesale cutting down of the film probably explains the painfully clunky voice-over which bookends the film. The beginning is particularly harsh, an awful example of what happens when you tell rather than show. It introduces us to the six men, in a way which seems more like notes from a casting call than anything: “Globke, the boy, who somehow through it all, had held on to fragments of his youth and innocence. Tillig, who asked for little, except the chance to laugh again.” Mind you, outside of Koertner and Wirtz, they might as well be cardboard. In this version at least, we learn next to nothing about the others, before they get blown up. Franz Loeffler (Cornthwaite) is kind to animals. That’s the level of character building we see here, and their deaths have little or no impact as a result.

Instead, it’s built around a clash of ideals between Koertner and Wirtz, with the former gradually incubating a burning hatred of the latter, and everything for which he stands. That reaches boiling point after Wirtz refuses to call off the death pool and donate it to the wife and child of the only married colleague, after he gets thinly distributed over a Berlin bomb-site. Apparently, unilaterally telling him where to stick it does not occur to Koertner and Loeffler, even though they form a majority. Instead, tensions build until the inevitable face-off, in which Koertner and Wirtz are both sitting next to one of those evil British bombs. Will they prove capable of teaming up, with Wirtz showing he’s a decent fellow at heart? Or does his selfish streak run so deep, that he is willing to sacrifice the man alongside whom he has fought and worked through the worst of the war, simply for financial gain?

The best sequences are those involving the bombs, with the explosive devices taking on an almost animated feel of malevolence. What stands out is how remarkably low-tech an approach had to be taken in those days (compare and contrast more recent bomb-disposal pic, The Hurt Locker): tools were nothing more advanced than a potentially dodgy pulley system with a rope, that allowed fuses to be unscrewed remotely. Removing them, though? 100% down to the man involved. And that’s discounting the threat posted by the environment, which could be underwater, or in a damaged building that could collapse at any moment. As a side note, startling to realize that, close to fifteen years after the end of the war, there were still enough bombed-out structures in Berlin that they could be used as locations by a film company.

Overall, this definitely feels informed by Henri-Georges Clouzot’s The Wages of Fear from 1953, also about a band of men taking on potentially lethal employment, and the rivalry that develops between them. Though rather less successful here are the more conventionally dramatic scenes, especially the squabbling between the two men over the affections of Margot which is trite and thoroughly unconvincing. That said, there is one scene where Chandler surpasses Palance (who throughout this, bears a weird resemblance to Christian Slater), getting a great speech to explain the thinking behind his philosophy: “Only a fool doesn’t take care of himself first.” It’s a nice bit of humanizing a character who, to that point, has been thoroughly unlikable.

Overall, this definitely feels informed by Henri-Georges Clouzot’s The Wages of Fear from 1953, also about a band of men taking on potentially lethal employment, and the rivalry that develops between them. Though rather less successful here are the more conventionally dramatic scenes, especially the squabbling between the two men over the affections of Margot which is trite and thoroughly unconvincing. That said, there is one scene where Chandler surpasses Palance (who throughout this, bears a weird resemblance to Christian Slater), getting a great speech to explain the thinking behind his philosophy: “Only a fool doesn’t take care of himself first.” It’s a nice bit of humanizing a character who, to that point, has been thoroughly unlikable.

According to Wikipedia, the film was titled The Phoenix in the UK, reflecting the title of the original novel by Lawrence P. Bachmann. However, I’ve not found a single promotional poster or still reflecting that title, so I have my doubts. After some further, largely unhappy directorial experiences in Europe, Aldrich returned to Hollywood and resurrected his career with Whatever Happened to Baby Jane? But due to this one-off entity, he’s probably the highest-profile director to have worked for Hammer, who tended typically to keep things in house. I’d be hard pushed to call the results an unqualified success. Yet if it’s a failure, it’s an interesting one.

This review is part of Hammer Time, our series covering Hammer Films from 1955-1979.