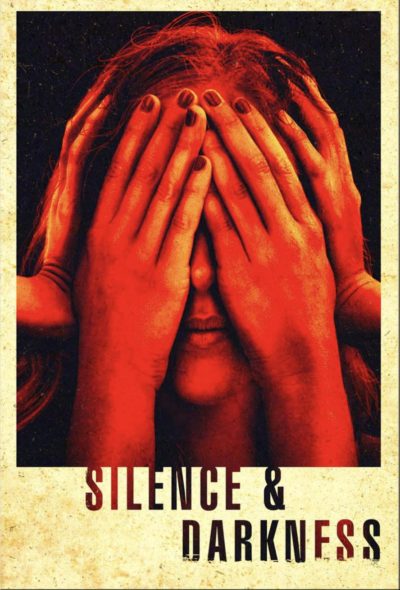

Rating: B-

Dir: Barak Barkan

Star: Mina Walker, Joan Glackin, Jordan Lage, Ariel Zevon

This is a very slow burn. So slow, in fact, there are times when you might be forgiven for thinking the fuse on it has gone out entirely. That would be a mistake. If you stick with it to the end, the resulting payoff will stick with you in return. What we have here could be the most disturbing portrayal of a medical practitioner since Dead Ringers. The doctor in question (Lage) has two daughters, both who are disabled, and live with him in a very nice, but remote, house. Beth (Glackin) is deaf, while Anna (Walker) is blind. However, together, they form a surprisingly fully-functioning unit. Mom is out of the picture, having died in murky circumstances, leaving Dad to raise the children.

Which is a problem. Because after it initially seems he’s a devoted father, the more we learn about him, the more unsettling things gradually become. The first point of concern is that he’s having an affair with one of his patients, and has an oral fixation (an assignation is brought to an abrupt end when he discovers she hasn’t been flossing). Shady, to be sure – yet, hey. we’ve seen worse. Alarm bells really start going off though, when a neighbour shows up, hysterical, her dog having found a human bone on his property. The doctor promises her he will take care of the situation. And he does. By heading out there with a shovel in the dead of night. Okay. That’s some threat level orange behaviour.

Which is a problem. Because after it initially seems he’s a devoted father, the more we learn about him, the more unsettling things gradually become. The first point of concern is that he’s having an affair with one of his patients, and has an oral fixation (an assignation is brought to an abrupt end when he discovers she hasn’t been flossing). Shady, to be sure – yet, hey. we’ve seen worse. Alarm bells really start going off though, when a neighbour shows up, hysterical, her dog having found a human bone on his property. The doctor promises her he will take care of the situation. And he does. By heading out there with a shovel in the dead of night. Okay. That’s some threat level orange behaviour.

And our concern proves fully justified. It’s clear that he treats his daughters as experimental guinea-pigs, with a drawer full of tapes in his surgery, documenting their “progress”. Things escalate further after Beth falls prey to a mysterious “virus,” and is whisked off despite the protestations of her sister. When she returns, Beth is literally not the person she used to be, and Anna decides that her father must be stopped. Although, in keeping with the low-key approach of the film, the climax of the film is understated, depicted from her point of view i.e. visually impaired. Then there’s the final whammy, as we hear some of the father’s earlier tapes, and everything that has happened reaches new depths of grimness.

For the majority of the running time, we watch, uncomprehendingly, as Anna and Beth communicate in sign language. Their relationship is obviously a deep one, with music being a particular focus. Yet the film, quite deliberately, leaves the viewer on the outside for long stretches. It may be this shared closeness, excluding him, which triggers their father into taking action to split them up. It’s increasingly uncomfortable to be sharing his perspective, and there was not much, emotionally, with which I found I could engage, beyond queasiness over the father’s actions. However, the three performances at the core are strong, and it’s definitely a film whose resolution will stick with me – even if it’s a movie few people may want to see more than once.