Rating: C+

Dir: Don Sharp

Star: Christopher Lee, Barbara Shelley, Richard Pasco, Dinsdale Landen

Excuse me, Hammer: we prefer the term “differently sane” these days… At first thought, this feels like the only foray by Hammer into a movie based on actual historical events. Well, I suppose Dracula was based on real Romanian prince, Vlad Tepes, and several Robin Hood films. But one parallel might be found back during their very early days. In 1935, Hammer’s second feature was The Mystery of the Mary Celeste, starring Bela Lugosi. It was based on the famous ship found floating, deserted, in the Atlantic; their explanation was a psycho serial killer among the crew. As for Rasputin, it came out 50 years after his death – close enough for some changes to be needed to avoid legal hassles.

I’m just not very well equipped to comment on how accurate this film is, however. Going in, almost all I could tell you about Rasputin, I learned from Boney M, and question the accuracy of the German Milli Vanilli as a credible source. It seems likely Russia’s greatest love machine was indeed big and strong, in his eyes a flaming glow. And quite plausible that most people looked at him with terror and with fear. But to Moscow chicks was he really such a lovely dear? I do recall, as a youth, reading that his penis was supposedly cut off and preserved as a relic. I’m disappointed to learn (my Google search history grows ever more fucked) it subsequently turned out to be a sea cucumber. Though as is common with relics, there are multiple claimants to the title of the One True Rasputin Dick, so who knows?

Er, moving on. The movie charts the rise and fall of defrocked priest Grigori Yefimovich Rasputin (Lee), whose “talents” make him a favourite of the Russian Tsarina. But being generally unpleasant to everyone else, makes him a lot of enemies at court, who conspire to take him out, on a permanent basis. The movie comes down on the side of Rasputin having genuine skills. It begins with him curing an inn-keeper’s wife of her fever, by the laying-on of his hands. Though mostly what’s depicted is his powers of hypnosis, including the ability to compel somebody to kill themselves. On arriving in St. Petersburg, his first target is Sonia (Shelley), one of the Tsarina’s ladies-in-waiting, whom he encounters while she’s slumming it in a dive-bar.

That provides him with the necessary “in” to the royal family, and his influence only expands from there. He starts rubbing a lot of people the wrong way, in rubbing the Tsarina the right way. The growing band of his opponents include Sonia’s brother, Peter (Landen), and Dr. Zargo (Pasco), an associate of the monk who has turned on him. However, Rasputin proves impressively difficult to kill (per our historical reference, Boney M, “They put some poison into his wine… He drank it all and said, ‘I feel fine'”). Luring him with the prospect of some fresh Russo-totty. and tossing him from a window onto a frozen lake below turns out to be the solution.

Lee is, as ever, great, and you can see why he wanted to play the part (he’s not the only one: Rasputin has also been depicted on screen by Lionel Barrymore, Tom Baker, Alan Rickman and Gérard Depardieu) He regards his role as “one of the best things I’ve done,” and certainly goes for it, squeezing all the juice from lines like, “When I go to confession I don’t offer God small sins, petty squabbles, jealousies… I offer him sins worth forgiving!” He has the physical presence and screen charisma to pull it off, utilizing that famous gaze to masterful effect. Just like his role as Count Dracula, it compels the victim to do his bidding, and it’s entirely credible that people do. Though probably the coolest thing is the anecdote Lee recounted in a Fangoria #228 interview:

When I was a small boy, about 8 years old, I was in bed asleep one night and my mother woke me up and said, “Come down to the drawing room. I’m going to introduce you to two people. You won’t remember them, but you’ll remember one day that you met them.” I remember vaguely two men wearing hlack-tie tuxedos, having dinner with my mother and stepfather. One was Prince Yusupov and the other was the Grand Duke Dmitry, two of the five — we’re told — alleged assassins of Rasputin… And then in 1976, at the Beverly Hills Hotel in LA. I met Rasputin’s daughter, one of three legitimate children. And I thought, “My God, I hope she hasn’t seen the film.”

When he’s on-screen, the film is perfectly fine. The problem is, no-one can stand against the blistering intensity of Lee’s performance. It needs an equally strong protagonist, and neither Pasco nor Landen are up to the task. There isn’t that much of a plot, either, with the focus opposite Rasputin shifting several times over the course of proceedings, from Sonia to the Tsarina, to Peter and finally onto another enemy, Ivan (Francis Matthews). That character represents the lawsuit-happy Prince Yusupov, still alive at the film’s release. For Yusupov had successfully sued MGM in 1932 over their film, Rasputin and the Empress, a case which led to the now-standard movie disclaimer, “Any similarity to a living person…” Even those whose knowledge of the subject is limited to seventies Euro-disco songs, should be aware of how it’s going to end, so there’s no real tension to be found.

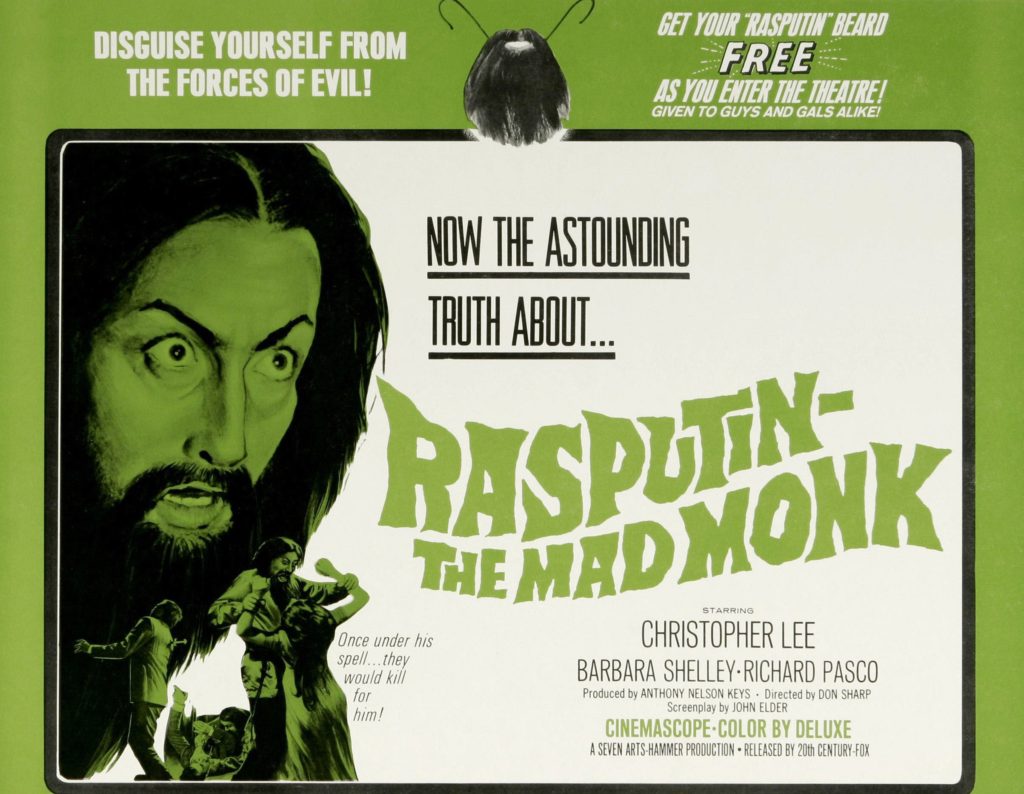

As the poster above and trailer below indicate, ticket buying was encouraged by the give-away of a free Rasputin beard, “given to guys and gals alike”, and in some territories, it was released on a double-bill with The Reptile. The film was shot back-to-back with Dracula, Prince of Darkness, and you may well recognize some of the sets, with Drac’s castle becoming a royal palace. Despite the parallels between Rasputin and Dracula, as well as the inclusion of some horrific elements, such as a severed hand and an acid attack, I couldn’t bring myself to classify this as a horror film. It’s more a slightly sordid melodrama, and if there’s a moral here – as in all good melodramas – it’s probably, be nice to the people you meet on the way up, because you’ll see them again on your way down. In Rasputin’s case, when you are plummeting past them, out of a palace window.

This review is part of Hammer Time, our series covering Hammer Films from 1955-1979.