Rating: C

Dir: Val Guest

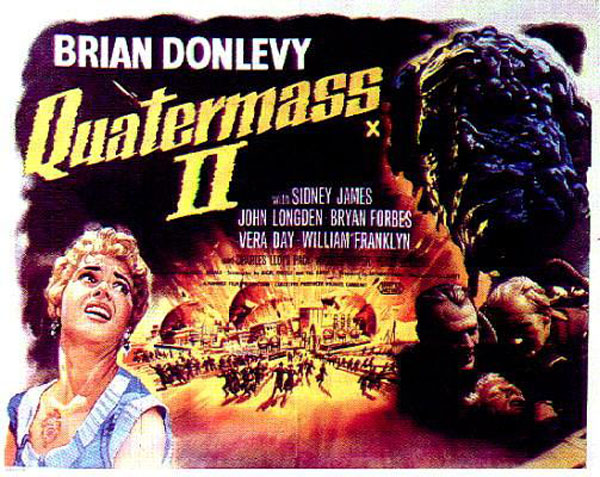

Star: Brian Donlevy, John Longden, Sid James, Bryan Forbes

a.k.a. Enemy From Space

Later in the same month which saw the release of The Curse of Frankenstein, May 1957, Hammer also put out a sequel to their hit from two years previously, The Quatermass Xperiment. While far from a flop, it’s safe to say that this was severely overshadowed by its Gothic sibling: this is perhaps indicated by the fact it would be a decade before Hammer would get round to another installment in the Quatermass franchise.

Like its predecessor, it was based on a successful TV series written by Nigel Kneale. Hammer bought the rights based purely on the scripts, well before it was screened in the winter of 1955 [as Quatermass II, a nice way to differentiate them!] During the 2½ years it took Hammer to make it, a good chunk of the cinematic thunder was perhaps stolen by Don Siegel’s Invasion of the Body Snatchers, which was released in February 1956. Both movies cover a similar theme, of an alien invasion by stealth, which also works as political allegory. Though to be fair, both these adaptations probably also owe a significant debt to Robert Heinlein’s 1951 novel, The Puppet Masters.

As in Xperiment, we begin with a courting couple in peril: here, the man has suffered some kind of trauma after picking up a rock, while on a picnic. They encounter Quatermass (Donlevy), who is still working on getting a rocket into space, this time with an atomic engine. His research center detects a steady steam of meteors with a weird trajectory descending in the same area, triggering Quatermass’s interest. He and colleague Marsh (Forbes) visit the the location, only to find a mysterious and heavily-secured government facility. After contacting a meteorite and falling ill, Marsh is taken away by the armed guards. Quatermass is unable to get the authorities to investigate, save for old pal Inspector Lomax (Longden).

Through Lomax, Quatermass wangles a spot on a parliamentary tour of the facility, supposedly engaged in producing synthetic food. However, the real purpose is to provide an artificial home for creatures that descend to Earth inside the meteorites, then attach themselves to human hosts, mind-controlling them thereafter. Investigating with the help of journalist Jimmy Hall (James), and the assistance of a fortuitous off-target meteor, they succeed in rousing the local population, and stage a raid on the facility, intending to expose its true nature. Meeting stiff resistance, Quatermass ends up barricaded inside a control room. Which turns out to be the perfect place from which to sabotage the entire endeavour, of course, while his atomic rocket gets crashed into the aliens’ orbiting base.

Through Lomax, Quatermass wangles a spot on a parliamentary tour of the facility, supposedly engaged in producing synthetic food. However, the real purpose is to provide an artificial home for creatures that descend to Earth inside the meteorites, then attach themselves to human hosts, mind-controlling them thereafter. Investigating with the help of journalist Jimmy Hall (James), and the assistance of a fortuitous off-target meteor, they succeed in rousing the local population, and stage a raid on the facility, intending to expose its true nature. Meeting stiff resistance, Quatermass ends up barricaded inside a control room. Which turns out to be the perfect place from which to sabotage the entire endeavour, of course, while his atomic rocket gets crashed into the aliens’ orbiting base.

One of the rather more distracting elements is the presence in the supporting cast of James, soon to become a comedy icon in the Carry On series, but for now still known as “Sidney” – and given second billing on the poster, behind Donlevy. Initially, it seems his journalist is the same kind of loud, wisecracking character for which he’d become famous. But when he sobers up (literally), the tone depicted becomes rather more serious, and even tragic. But I found it impossible to separate his Jimmy Hall from the likes of future characters like Sir Sidney Ruff-Diamonds, and the result is rather jarring. That’s more me than him, clearly. Outside of Donlevy, the rest of the cast just don’t make much impression, and it’s a film whose success is almost entirely dependent on the story.

As such, I found the first half, when it’s a well-crafted paranoid thriller, worked considerably better than the latter stages, where our hero rouses the contemporary equivalent of a mob with torches and pitch-forks. That’s not very scientific, Professor Quatermanss. For once, Hammer made particularly good use of locations. This may be the sole film whose opening credits include thanks to Hemel Hempstead, then under construction as a “new town”, and which presumably provided the under-construction roads, etc. Meanwhile, the Shell Haven Refinery in Thurrock is made to look particularly menacing, standing in for the alien facility. There’s also no denying the political subtext, though I’ve read reviews painting it both ways, as a critique of socialism or of conservative principles.

There’s no reason it can’t be both. According to Kneale, “Quatermass II was about the evil of secrecy. It was a time when mysterious establishments were popping up: great radar establishments and nuclear establishments like Harwell and Porton Down for germ warfare.” That’s certainly a theme which comes through. Those not directly connected are prepared to give a pass to anything, once the holy words “in the interests of national security” are uttered. Of course, at the time, we were still less than a generation removed from World War II: loose lips sink ships, and all that. But on the other hand, this was the same decade where the UK government were testing nerve gas on soldiers, while telling them it was cold research. Kneale’s qualms seem legitimate, regardless of political shade.

It does over-reach itself significantly at the end, after the gigantic creatures are released from their holding tanks (above), to wobble dubiously across a model landscape for a bit. Even by comparison, say, to Godzilla, released in 1954, the monsters don’t look even slightly credible. You can understand why Hammer would shift away from film requiring this kind of large-scale spectacle going forward. But, no doubt helped by the Quatermass name, it still proved capable of returning a profit for the company. In the UK, it was released on a double-bill with Brigitte Bardot vehicle, And God Created Woman, which is certainly an interesting exercise in programming.

I do feel it’s probably the least effective of the four Hammer Quatermass films [that includes Unknown, a Q-movie in all but name], mostly because of what feels like an abrupt shift in tone over the second half to less effective action-movie territory, never Kneale’s strength. Its central topic was also covered more effectively in Body Snatchers, and that movie’s landmark status leaves this feeling like it falls short in originality. Shiver-inducing moments like the company’s trucks being driven through central London, past an oblivious population, only hint at what could have been.

This review is part of Hammer Time, our series covering Hammer Films from 1955-1979.