Rating: C

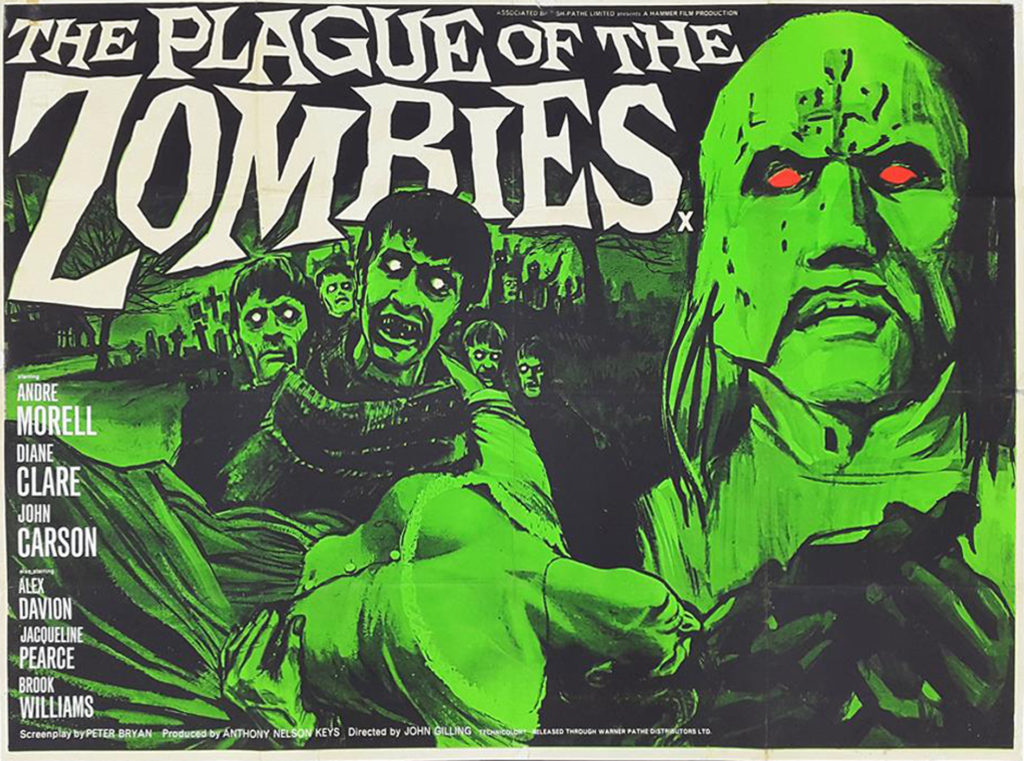

Dir: John Gilling

Star: André Morell, Diane Clare, Brook Williams, John Carson

I think I’m going to start calling myself Sir James. Based on the reactions the lead character gets here when he drops his knighthood, it just makes life that much easier. Bolshy group of local yokels in the pub? Tell them you’re a sir, add a “Landlord, see these gentlemen have a drink with me, will you?” and the forelocks suddenly can’t get tugged quickly enough. It also, apparently, lets you casually ask the vicar, “I am given to understand that you have a fine collection of books on a variety of subjects. I wonder if you have any on witchcraft or black magic?” I’d be looking around very nervously if someone asked me that. But it’s all in line with a film which is as much about notions of class as it is about… oh, black magic and zombies.

Both the protagonist and antagonist here are aristocrats. On the side of good is Sir James Forbes (Morell), Professor of Medicine at London University. He travels to Cornwall, with daughter Sylvia (Clare, though her lines were subsequently dubbed by Olive Gregg) to investigate a mysterious series of deaths. Weirder is to follow, as the supposed corpses keep being seen on the moors around the village. The evidence gradually points toward Squire Clive Hamilton (Carson), recently returned from the West Indies, and possessing an unexplained income stream. Turns out he’s using non-union labour in his tin mine, to put it mildly.

While generally well-regarded, I must say, outside of one brilliant sequence, I found this rather boring. In its defense, the overkill of zombies during the last decade doesn’t help, even if these are not your usual walking dead. But once it gets past the set-up, the story doesn’t have anywhere much to go. It’s entirely clear Squire Hamilton is the villain, and the title largely gives away his method. It doesn’t provide sufficient scope for dramatic conflict, save the largely unexplained quest by Hamilton to turn Sylvia into a zombie. I mean, is she going to toil away in the mine? It’s also blatant cultural appropriation on his part. I mean, he doesn’t even acknowledge voodoo’s origins, relegating its original practitioners to the role of his rhythm section. That won’t get any approving retweets. Though, hey, at least it’s not Michael Ripper in blackface.

While generally well-regarded, I must say, outside of one brilliant sequence, I found this rather boring. In its defense, the overkill of zombies during the last decade doesn’t help, even if these are not your usual walking dead. But once it gets past the set-up, the story doesn’t have anywhere much to go. It’s entirely clear Squire Hamilton is the villain, and the title largely gives away his method. It doesn’t provide sufficient scope for dramatic conflict, save the largely unexplained quest by Hamilton to turn Sylvia into a zombie. I mean, is she going to toil away in the mine? It’s also blatant cultural appropriation on his part. I mean, he doesn’t even acknowledge voodoo’s origins, relegating its original practitioners to the role of his rhythm section. That won’t get any approving retweets. Though, hey, at least it’s not Michael Ripper in blackface.

That amazing scene, though. Hammer didn’t really go for bravura set-pieces; when their films work, it’s mostly down to the skillful generation of overall atmosphere and strong performances. Here, on the other hand, Gilling throws everything he has at the viewer in a four-minute chunk, beginning almost exactly on the hour mark. It begins with a beautiful woman rising from her grave, only to be decapitated, and somehow manages to get creepier from there. A horde of zombies rise from the cold earth, moving with that implacable relentlessmess, stretching toward their victims. This may be the most memorable single scene in the Hammer filmography. It’s perhaps too good, because everything thereafter, not least a feeble finale, pales severely in comparison.

[November 2010] Made in 1966, this must have been one of the last movies to use the traditional, voodoo-based concept of the zombie, before George A. Romero forever turned the field on its head, two years later. In this movie, medical professor Sir James Forbes (Morell) gets a rambling note from former pupil, Dr. Thompson (Williams), detailing a mysterious illness affecting the Cornish village where he practices, taking the lives of the young and healthy. Forbes goes to visit, accompanied by daughter Sylvia (Clare), since she was a friend of Thompson’s wife, Alice. On arrival, they discover Alice, too, is fading away, and when the two doctors attempt to perform an impromptu exhumation of one of the victims, they discover the corpse missing from its coffin – and its brother swears he saw the deceased, walking on the moors. Is this, perhaps, connected to Squire Hamilton (Carson), and his time spent in the Caribbean? Oh, who am I trying to kid. Of course it is.

You could read a political subtext in here, and the film is riddled with class commentary e.g. the deference shown to Forbes in the village pub by the locals, it appears purely because he is a “proper gent.” Meanwhile, they are simultaneously being exploited, in the most heinous fashion, by the Squire for commercial ends, and neither side treat the women involved as much more than clothes-horses (nor, to be honest, does the script-writer). It’s an interesting tension of ideas. The film is also famous, rightly so, for a nightmarish sequence in a graveyard which includes both a surprisingly-graphic (for the time) decapitation, and memorable images of the undead clawing their way out of the ground, their skin “the color of television, tuned to a dead channel,” to borrow a line from William Gibson. Morell also turns in a fine performance as the lead, unwilling to stop niceties get in the way of finding the truth [in a similar vein, I note he was also Watson in Hammer’s Hound of the Baskervilles]

You could read a political subtext in here, and the film is riddled with class commentary e.g. the deference shown to Forbes in the village pub by the locals, it appears purely because he is a “proper gent.” Meanwhile, they are simultaneously being exploited, in the most heinous fashion, by the Squire for commercial ends, and neither side treat the women involved as much more than clothes-horses (nor, to be honest, does the script-writer). It’s an interesting tension of ideas. The film is also famous, rightly so, for a nightmarish sequence in a graveyard which includes both a surprisingly-graphic (for the time) decapitation, and memorable images of the undead clawing their way out of the ground, their skin “the color of television, tuned to a dead channel,” to borrow a line from William Gibson. Morell also turns in a fine performance as the lead, unwilling to stop niceties get in the way of finding the truth [in a similar vein, I note he was also Watson in Hammer’s Hound of the Baskervilles]

However, these aspects are overshadowed to a significant degree by more practical considerations. How did the Squire bring in the native drummers who accompany his ceremonies, and what do they do the rest of theim? Does he make all the zombies’ matching shrouds himself? The logistics of the central idea are so poorly thought-out, they threaten to derail proceedings entirely. And who moved Cornwall North of the Arctic Circle? I mention the last because, it never seems to get dark in this movie at all, even when people are supposedly creeping around in the dead of night. The cinematic technique on view here, needs to be known as “day for night mid-afternoon.” While there’s a bonus in the presence of Jacqueline Pearce as Alice – she’d go on to be uber-bitch Servalan in 80’s “classic” Blake’s 7 – but this feels closer to the zombie films of the 1940’s, than the genre apocalypse Romero was about to unleash. C+

This review is part of Hammer Time, our series covering Hammer Films from 1955-1979.