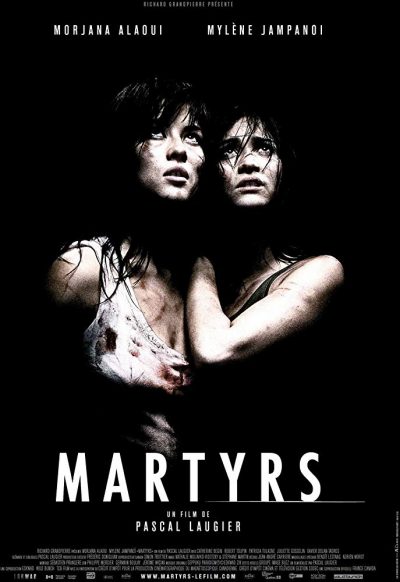

Rating: A

Dir: Pascal Laugier

Star: Mylène Jampanoï, Morjana Alaoui, Catherine Bégin, Isabelle Chasse

I hadn’t watched this since it kicked my arse back in 2009, and as usual, was a little concerned that it might not stand up to repeat viewing. I’d been somewhat forewarned before that original viewing as to its brutal and unrelenting nature, yet the reality was more gut-wrenching still. Could it possibly have as much impact again?

Hell, yes.

Not having seen the movie in close to nine years probably worked to its benefit. While some elements remained etched in my mind – and likely will be indelible – others had been more or less forgotten, especially in the early stages. I did remember it was the story of two young girls, Lucie (Jampanoï) and Anna (Alaoui), the latter of whom had escaped a life of truly horrific abuse, and been befriended by the former. Fifteen years later, Anna finds the couple responsible, an apparently “innocent” family, and takes her revenge. Except, it turns out, Lucie has to bear the brunt of what follows, for Anna was not the final victim. And nor were the couple the final perpetrators.

In case you haven’t seen it, I’ll say no more than that. Just be prepared for something thoroughly unflinching in terms of depicting just how incredibly fucked-up people can be to each other. That’s the astonishing thing, especially about the first half: as it unfolds, things happen which would form the terrible climax of many other horror movies. Yet Martyrs keeps on escalating past those points, until you suddenly realize we’ve gone all the way round, and the cycle is about to begin, all over again. Once more, that would be the point at which many lesser movies would roll the credits. Martyrs is just getting going.

In case you haven’t seen it, I’ll say no more than that. Just be prepared for something thoroughly unflinching in terms of depicting just how incredibly fucked-up people can be to each other. That’s the astonishing thing, especially about the first half: as it unfolds, things happen which would form the terrible climax of many other horror movies. Yet Martyrs keeps on escalating past those points, until you suddenly realize we’ve gone all the way round, and the cycle is about to begin, all over again. Once more, that would be the point at which many lesser movies would roll the credits. Martyrs is just getting going.

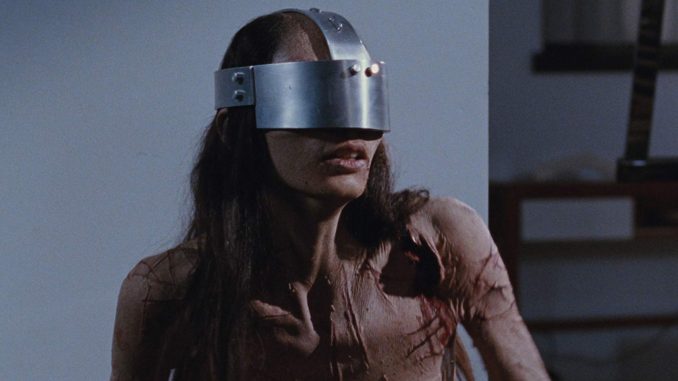

And so we get what feels like about ten hours of systematic abuse, without a single word being spoken. It’s only about fifteen minutes. It’s not simply to satisfy some twisted psychopathic need either. It’s for a very specific purpose, summed up in the chilling line, spoken by the woman (Bégin) behind it all: “The world has come to a point that there are only victims left.” The accuracy of that line may be the most disturbing thing about the film as a whole. Which is saying something, considering the number of moments here which got under my skin. It’s not all explicit gore, either. The end has Lucie whispering something to the woman: we never get to find out what, yet the impact of her words will have me wondering what they could have been, for weeks to come.

There was a particularly superfluous American remake a couple of years ago, with which I simply haven’t bothered. At best, it could only equal the original. More likely (far more likely, going by the reviews), it would be the gastronomic equivalent of listeria, poisoning my fondness for the real thing. I think I’ll pass: accept absolutely no imitations, for the best the New French Extremity has had to offer.

This article is part of 31 Days of Horror.

[December 2009] Having sat through most of the new wave of Euro-horror and seen that they largely fail to live up to the fanboy hype, it’s quite refreshing to report that I’ve finally found one that doesn’t disappoint. It perhaps helped that I wasn’t too aware of it before viewing, but this certainly has to go down as one of the most disturbing movies I’ve seen in a long time. The basic premise is nasty enough: Lucie (Jampanoï), a young girl is chained up in a basement, but escapes from her abusers.

Fifteen years later, she goes back to find them, and take bloody revenge with a shotgun. That, in itself, would make for quite a story. However, here, it’s only the starting-point, and the more we discover, the more unsettling things become. Lucie was helped by Anna (Alaoui): the two became companions in the institution where they grew up, but in the blood-drenched house, Anna discovers the truth about what happened to Lucie. Firstly, her friend was not the only victim – and it’s in this sequence that the words, “This is really fucked-up,” escaped my lips (and not for the last time). And then, we discover the reason for the torture. Yes: reason, for there is a philosophy behind it, and as you learn about that, the full impact of the film is finally delivered. Reading some other reviews, it seems to be remarkably divisive, even among horror fans, with every good review apparently getting blasted in the comments, and vice-versa. I can see both points of view, but don’t buy into the theory that this is just torture for the sake of it, under the cover of flimsy pseudo-theological pretensions.

While the torture is portrayed with unflinching detail [my heart goes out to poor Alaoui], you eventually realize the purpose. This is full-on confrontational horror, which doesn’t just show you the darkest part of human nature, it gives you an inkling of why people can do these things to others, and may even suggest that the end justifies the means – though the final shot (and I mean that in more ways than one), perhaps raises more questions than it answers. It’s no surprise that Laugier was attached for a while to the Hellraiser remake, as this shares much the same combination of religion, and transcendentalism through pain. It’s a supremely-twisted piece of no-holds barred film-making, that pulls no punches and, love it or hate it, will not easily be forgotten. A-