Rating: B-

Rating: B-

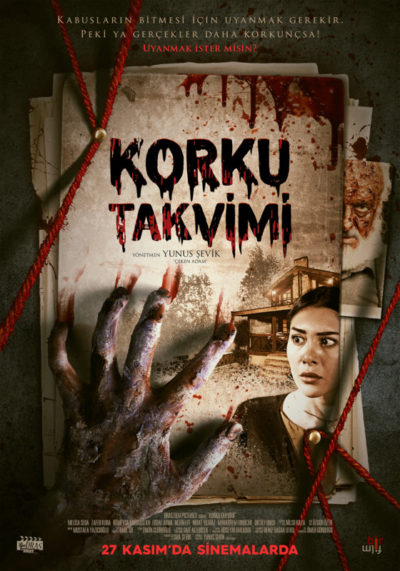

Country: Turkey

Dir: Yunus Şevik

Star: Melisa Seda, Zafer Kora, Rümeysa Sarıarslan, Nevin Efe

This isn’t quite the first Turkish film I’ve ever seen. But considering the only other that comes to mind is 1974’s Karate Girl. This is famous for all the wrong reasons, though as usual, the Internet reaction was severely overblown. Still, it’s probably not much help in terms of assessing where this sits in terms of Turkish cinema. I do get the sense there are definitely some cultural beats I am missing. Not the least of which may be a title that translates into English as Horror Calendar. I kept waiting for a calendar to show up. It never did. Mind you, there’s also a bow and whole quiver of arrows, hanging prominently on the wall of the house where this largely takes place. Contrary to the rule of Chekhov’s Gun Bow, this never comes into play either.

Hulya (Seda) is an actress who has finally got a lead role, despite a mental state best described as fragile. One shot requires her to be asleep, and she actually dozes off. But when she wakens, she’s still in the film, and there’s no trace of it being a cinematic endeavour. Her supposedly fictional husband, Tahir (Kora) explains her real name is Nevin, and the acting thing was her fantasy. It’s all part of a psychological disorder which has troubled her for years. Hulya/Nevin has, understandably, difficulty processing this. But the mounting evidence, in the form of photos, family members and even her doctor, whom she does recognize from her “other” life, suggests Tahir is right. So, mental illness, or gaslighting on a truly monumental level? Oh, yeah: there’s the spirit of a murderous priest, known locally as “Father Bloody”, wandering about. That doesn’t help anyone’s stability.

Hulya (Seda) is an actress who has finally got a lead role, despite a mental state best described as fragile. One shot requires her to be asleep, and she actually dozes off. But when she wakens, she’s still in the film, and there’s no trace of it being a cinematic endeavour. Her supposedly fictional husband, Tahir (Kora) explains her real name is Nevin, and the acting thing was her fantasy. It’s all part of a psychological disorder which has troubled her for years. Hulya/Nevin has, understandably, difficulty processing this. But the mounting evidence, in the form of photos, family members and even her doctor, whom she does recognize from her “other” life, suggests Tahir is right. So, mental illness, or gaslighting on a truly monumental level? Oh, yeah: there’s the spirit of a murderous priest, known locally as “Father Bloody”, wandering about. That doesn’t help anyone’s stability.

There are a couple of slightly off-center stylistic choices here. Seda’s performance, especially early on, seems melodramatic to the point of excess. While there is perhaps good reason for this, the high volume and intensity becomes a bit wearing. The image, top, is a fairly good representation of the average level at which the lead actress operates (again, understandably). Şevik also exhibits a great fondness for dropping into slight slow-motion for dramatic effect. I think less of this might have proved more successful. Initially, I was expecting the heroine to bounce back and forth between the film and “real” worlds. That doesn’t happen, for reasons explained in a lengthy coda, which answers most questions. Though it also poses some – in particular, about security procedures in Turkish mental health facilities.

It’s a little like One Cut of the Dead; not just in the film-within-a-film concept, also that there are elements here which will only make sense at the end. It would probably require a second viewing to see how rigorously the plot logic stands up to scrutiny. All told though, along with the cultural freshness, this offered enough of a novel twist on the “Is she mad?” sub-genre of psychological horror, to keep me interested right the way through.

This review formed part of our October 2021 feature: 31 Countries of Horror.