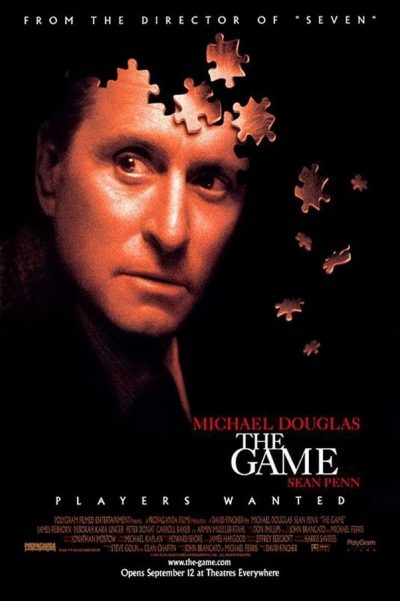

Rating: B+

Dir: David Fincher

Star: Michael Douglas, Deborah Kara Unger, Sean Penn, James Rebhorn

There’s a scene here where finance mogul Nicholas Van Orten (Douglas) is at the airport. His world is beginning to unravel at the seams, the apparent work of a company called Consumer Recreation Services (CRS), whose services were hired on behalf of Nicholas by his brother, Conrad (Penn). They provide “life-changing” experiences. Which in Nicholas’s case, start with a dummy left in his driveway – a reference to his father’s suicide on his 48th birthday, which our protagonist is fast approaching – and his TV talking to him, Videodrome style. They then build to the point where this master of the universe no longer directs any aspect of his own life. Which is how we find him at the airport: he no longer trusts anyone or anything, and scans the other people there, trying desperately to figure out who are CRS stooges. It’s an impeccable depiction of a world which has become built entirely out of paranoia.

As such, Douglas is perfect for the part, which has echoes of two previous roles. He starts the film as Gordon Gecko from Wall Street, slick, and in absolute control. But ends it as the unnamed protagonist from Falling Down, known as “D-Fens”, with everything he has held dear crashing down around him, despite his increasingly desperate efforts. One difference from the latter: rather than him merely being collateral damage, this world is out to get Van Orten. Or is it? And that’s the fun here: we ride along with him on the downward spiral, from penthouse to pavement and beyond. We don’t know who to trust or what to believe either, until we wake up, buried alive in a Mexican graveyard. But there’s more than a little A Christmas Carol here too, with well-crafted psychological trauma as therapy. What does not kill you, may make you a better person, the film seems to be saying.

As such, Douglas is perfect for the part, which has echoes of two previous roles. He starts the film as Gordon Gecko from Wall Street, slick, and in absolute control. But ends it as the unnamed protagonist from Falling Down, known as “D-Fens”, with everything he has held dear crashing down around him, despite his increasingly desperate efforts. One difference from the latter: rather than him merely being collateral damage, this world is out to get Van Orten. Or is it? And that’s the fun here: we ride along with him on the downward spiral, from penthouse to pavement and beyond. We don’t know who to trust or what to believe either, until we wake up, buried alive in a Mexican graveyard. But there’s more than a little A Christmas Carol here too, with well-crafted psychological trauma as therapy. What does not kill you, may make you a better person, the film seems to be saying.

Obviously, it’s the kind of film where your reaction will depend on how you take to its ending, which zigs one way, then does a 180 to head off in the complete opposite direction, before turning back in on itself. [Not for nothing is CRS’s logo a physically-impossible object!] You can either applaud its audaciousness, or snort derisively at its idiocy: I wouldn’t unfriend you for either. As such, it may not be a film that repays repeated viewing – it’s likely been fifteen or more years since I’ve watched this, enough time for it to seem fresh again. Though it would also be interesting to watch again, and spot the potential forks in the road down which Van Orten travels. What would have happened, say, if he had helped the guy in the airport restroom?

The approach plays into the sense we’ve all had, that there is some higher force at work, directing our lives – whether for our benefit or their own amusement. It’s much the same sense of personal powerlessness which fuels Fincher’s subsequent, cultier Fight Club, but I think this has likely stood the test of time better. It’s a neon-drenched nightmare that looks as good as anything else Fincher has made, before or since, with a script which feels like something on which a grumpy David Mamet might have worked. And bonus points for any film which uses Jefferson Airplane’s White Rabbit as a backdrop to a home invasion – especially one that’s all the more creepy for lacking any actual invaders.

Original review. Douglas does Character #2 (the Sleazeball Executive – see also Indecent Proposal and Wall Street) in this very twisted tale of what to get the man who has everything: how about paranoia and a selection box of psychoses? For this is what he gets, thanks to a very dubious birthday gift from brother Penn. But is it just the game of the title, or is more going on? After Se7en plundered Blade Runner, Fincher decides to loot the Videodrome cupboard, right down to using the same composer, Howard Shore, so the man has excellent taste in movies. It’s all deeply confusing; the lead character never knows what’s going on, and neither does the audiece, right up until the last moments. Still totally implausible, of course, but none the worse for it, despite an ending which could have used some more ambiguity. B