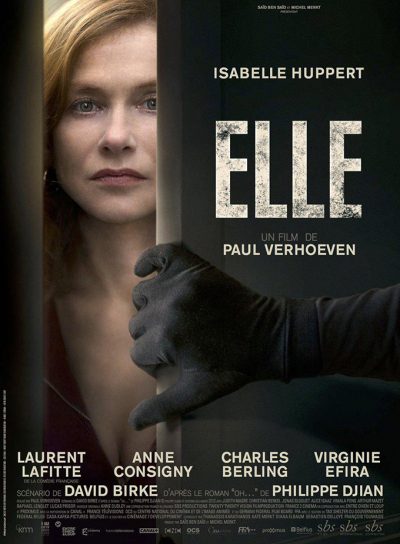

Rating: B+

Dir: Paul Verhoeven

Star: Isabelle Huppert, Laurent Lafitte, Anne Consigny, Charles Berling

It has been a decade since Verhoeven’s last feature, Black Book, if you discount his gimmicky yet effective made-for-TV piece, Steekspel. That’s a shame, for even as he heads towards his seventy-ninth birthday, he clearly hasn’t lost any fragment of his ability to tweak liberal sensibilities, something he has been doing for most of his career. In this case, it’s the relationship that forms between a woman and her rapist. Conventional wisdom refuses to acknowledge this as even a possibility, and has lead to frenzied screeds in places like The New Yorker, dismissing the film as a result. “Normal” women don’t behave like this! But the heroine here, Michèle Leblanc (Huppert) is far from normal – no surprise, since when has Verhoeven ever been interested in the norm?

This is clear immediately from the get-go. We hear, rather than see, the assault, and afterward, Michèle’s reaction is unabashed calm, to the extent it’s unclear immediately whether or not the sex was consensual. For she cleans up the debris, changes her clothes, and doesn’t bother to mention what turns out to to be a savage home invasion to her son, who arrives shortly afterward. No, she’s made of far sterner stuff than to let mere rape derail her life. Hell, in further derailment of expected protocol, Michèle runs a video-game company, doesn’t care who she treads on in so doing, and is having an affair with the husband of her best friend. So, when her rapist sends her an appreciative text-message and it becomes apparent he’s still hanging around… Game on.

This is clear immediately from the get-go. We hear, rather than see, the assault, and afterward, Michèle’s reaction is unabashed calm, to the extent it’s unclear immediately whether or not the sex was consensual. For she cleans up the debris, changes her clothes, and doesn’t bother to mention what turns out to to be a savage home invasion to her son, who arrives shortly afterward. No, she’s made of far sterner stuff than to let mere rape derail her life. Hell, in further derailment of expected protocol, Michèle runs a video-game company, doesn’t care who she treads on in so doing, and is having an affair with the husband of her best friend. So, when her rapist sends her an appreciative text-message and it becomes apparent he’s still hanging around… Game on.

In hindsight, he could have done better in his choice of victim. For what we discover – after an odd incident where she is abused in a cafe – is that Michèle is an extremely notorious daughter. When she was 10, her father went on a rural killing spree and killed 27 people, six dogs and a couple of cats, though as she points out, he spared a hamster. [It’s worth mentioning that this is likely the funniest rape-revenge movie of all time, providing your comic sensibilities stretch to the deadpan and very dark] Her precise role in this event is never less than murky; witness, accomplice after the fact or maybe even more. What becomes clear is that her hunter, whoever he might be – and there is no shortage of potential candidates – is increasingly the hunted.

If a well-crafted mix of genres, at 130 mins, this is likely guilty of trying to cram too much in. Some of the subplots, such as Michèle’s son and his psycho girlfriend, or her mother and her toyboy, feel more like random afterthoughts than well-connected pieces of the puzzle. But courtesy of Huppert’s expert performance, the heroine becomes an increasingly complex and multi-layered creature: at times you feel nothing except sympathy for her, then she’ll do something which turns her into a total bitch. It’s almost like she’s that rarest of butterflies in Hollywood films – a real person. Not even the rapist is “all bad”. Again, it’ll raise the hackles of your local social justice warrior, but having known at least two multiple murderers, I can safely assure you of this: people are complex.

This, however, is simply what Verhoeven does: subvert common conceits. Take Starship Troopers. Sure, Verhoeven knows from personal experience about the drawbacks of fascism, having grown up in occupied Holland during World War 2. But in ST, he depicts a fascist society which seems to work a damn sight better than the current one, having apparently eliminated poverty and need entirely. Instead, he creates a rabble-rousing crowd-pleaser which was probably the most effective propaganda film since the end of World War II. Do you want to know more? The approach is similarly ambivalent here. Rape is bad, m’kay? But here, it kick-starts a series of events and, by the end, you can certainly argue that Michèle has become liberated and a better person as a result. So…

It’s the kind of film which leaves you perplexed and trying to make sense of what you’ve been told. Is the message here, “When life gives you lemons…”? Much as Verhoeven brought a Hollywood outsider’s eye to action films in Robocop, here he has brought a Gallic outsider’s eye to French culture, and delivered something which, in characters and situations, is as much a parody of its cinema as an example of it. For instance, at times, it appears that everyone is cheating on their respective partners with someone else. On another level, it could almost be seen as a prequel to Verhoeven’s most (in)famous film, Basic Instinct. You can imagine Michèle moving to California, changing her name to Catherine Tramell, and starting a new career, writing steamy novels of murder, based on personal experience.

It’s the kind of film which leaves you perplexed and trying to make sense of what you’ve been told. Is the message here, “When life gives you lemons…”? Much as Verhoeven brought a Hollywood outsider’s eye to action films in Robocop, here he has brought a Gallic outsider’s eye to French culture, and delivered something which, in characters and situations, is as much a parody of its cinema as an example of it. For instance, at times, it appears that everyone is cheating on their respective partners with someone else. On another level, it could almost be seen as a prequel to Verhoeven’s most (in)famous film, Basic Instinct. You can imagine Michèle moving to California, changing her name to Catherine Tramell, and starting a new career, writing steamy novels of murder, based on personal experience.

Elle shares with Instinct a distinctly Hitchcockian edge, not least in the aspect of observing and being observed. Michèle is not only watched by her rapist, she tacitly observes the hunky husband (Lafitte) from the house across the street, our heroine masturbating as she watches him put up Christmas lights with his uber-Catholic wife. The cynicism we get here about those who profess religious faith is another trademark of a director who has never had much time for this part of the human psyche. It goes all the way back to The Fourth Man, where Jeroen Krabbe’s deranged writer fantasized about giving Jesus a blow-job on the cross. [Verhoeven also once said, “It looks to me as if the whole Christian religion is a major symptom of schizophrenia in half the world’s population.”]

While it’s certainly not perfect, Elle is more challenging of truths generally perceived as self-evident – often the best kind to challenge – than virtually any other film I’ve seen this year. If Verhoeven could just up his damn output to more than one movie every 10 years, the cinematic world would be all the better for it. Though at this point, I think I’d just settle for him getting out of 2016 with his pulse intact. For that obituary montage during the Oscars is already going to be more than long enough.