Rating: C

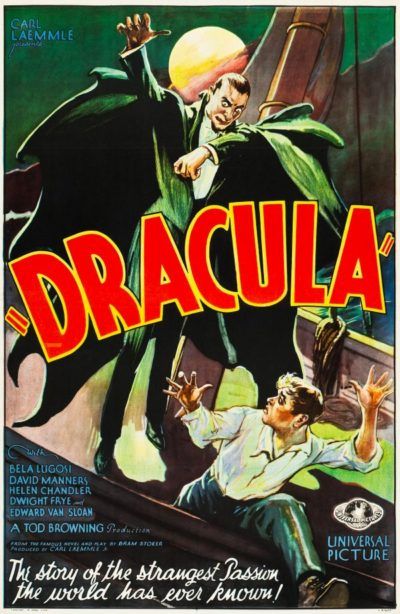

Dir: Tod Browning

Star: Bela Lugosi, David Manners, Helen Chandler, Dwight Frye

The above grade doesn’t reflect the impact this had, being perhaps the first popular horror movie and introducing the cinematic version of Count Dracula to a wide audience, or its absolute, undeniable place in horror history. However, there’s equally no denying its flaws, in particular a slew of bland, largely uninteresting people on the human side – to the point you should be forgiven if you find yourself cheering for #TeamDracula. While the structure largely follows Bram Stoker’s novel, there are some changes. The most significant and interesting, is that it’s Renfield (Frye) who visits Dracula in his castle, rather than Jonathan Harker. That’s how Renfield eventually becomes the Count’s minion – albeit an insane one held in Dr. Seward’s asylum. Thereafter, it follows the normal structure: Dracula returns to England, and vamps Lucy and Mina, before Van Helsing shows up with a delivery of stake.

Lugosi had portrayed Dracula in a 1927 Broadway play, but was far from the studio’s first choice. Considering how iconic Lugosi now is, it’s hard to believe the role originally went to Lew Ayres, best known as Dr. Kildare in the thirties and forties. Bela is the best thing about this, imbuing every sentence with a thousand pounds of menace, e.g. “I never drink… wine…” The problem is, like Christopher Lee in the Hammer films, Lugosi is on-screen less than you might think. Unlike the Hammer films, there’s no Peter Cushing to provide focus when Dracula isn’t around. Oh, Edward Van Sloan tries his best as Van Helsing, even if he is no Cushing. The issues are John Harker (Manners) and Mina Seward (Chandler), who appear to be competing for Upper-class Twit of the Year, or Charles K. Gerrard as Renfield’s attendant, who appears to have inspired Dick Van Dyke in Mary Poppins.

There are a couple of elements which are still notable. The first of these is the almost total absence of music. This was still in the very early days of “the talkies,” and the concept of composing music for a film was still relatively novel and, in this case, deemed an unnecessary cost. Outside of, oddly, a bit of Swan Lake over the opening credits, the film unfolds with virtually no musical cues; it would take 67 years before Philip Glass would be commissioned to compose a score. Yet there are points at which it feels like this works in the movie’s favour, the background silence becoming almost uncomfortable. On the other hand, despite being pre-Hays Code, it is almost painfully restrained, with everything from any vampire attacks to the staking of Dracula, occurring out of shot

There are a couple of elements which are still notable. The first of these is the almost total absence of music. This was still in the very early days of “the talkies,” and the concept of composing music for a film was still relatively novel and, in this case, deemed an unnecessary cost. Outside of, oddly, a bit of Swan Lake over the opening credits, the film unfolds with virtually no musical cues; it would take 67 years before Philip Glass would be commissioned to compose a score. Yet there are points at which it feels like this works in the movie’s favour, the background silence becoming almost uncomfortable. On the other hand, despite being pre-Hays Code, it is almost painfully restrained, with everything from any vampire attacks to the staking of Dracula, occurring out of shot

We also need to address the armadillo in the room. Yes: armadillo. For these creatures are seen wandering the halls of Dracula’s castle, despite not exactly being a creature native to Transylvania (they are, however, native to Transylvania County, North Carolina). I’ve read several theories as to why Browning put them in the movie, from them being a disease vector – you can get leprosy from an armadillo – to them being a replacement for rats, the rodents being deemed unsuitable for use in movies. Personally, I prefer the idea Browning simply liked armadillos. If I ever make a vampire film, you can be damn sure I’m going to have a narwhal in there. I also note, garlic is replaced by wolfsbane as the anti-vampire herb of choice.

All told though, this is largely quite a plodding version, whose origins in a Broadway play are often highly obvious. This is a very theatrical and static production in terms of its staging. Outside of Lugosi, the fun is mostly to be found watching Renfield chew up the scenery in every scene after he goes mad. Even at a relatively terse 75 minutes, it struggled to hold my attention when Dracula was not about, and the underwhelming nature of its ending was surpassed only by its abruptness.