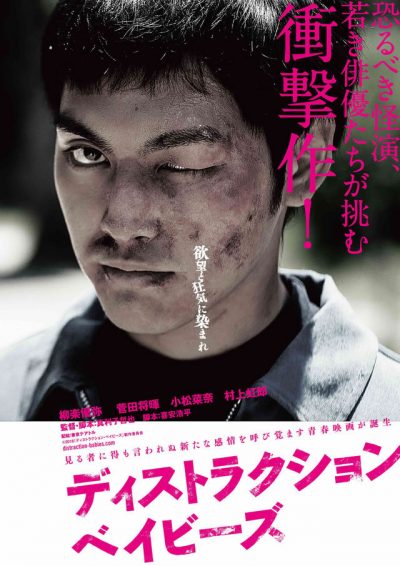

Rating: C

Dir: Tetsuya Mariko

Star: Yuya Yagira, Masaki Suda, Nana Komatsu, Nijiro Murakami

This is probably the first time I’ve ever had to look up a film’s title while I was actually watching it. I knew it was something Babies. Delinquent? Dangerous? Couldn’t for the life of me remember. It’s probably meaningful that I remember the DVD tagline more – albeit for being utterly inaccurate. I mean, when you state your film is “The most extreme 108 minutes in Japanese cinema history,” you’ve got to be able to back up that shit. The only remorely corroborating source I can find is a review which prefixed the statement with “Is this…”, then never answers its own question. Though for anyone seriously to make such a claim, their knowledge of Japanese cinema must be limited to the works of Hayao Miyazaki. Everybody else? Go watch Ichi the Killer. Then get back to me about “extreme”.

In the film’s defense, it’s possible this would have more impact if you’re familiar with the social setting and structures. For instance, part of the backdrop is the “battle of the portable shrines”, which is an actual thing, a historical remnant of institutionalized violence – perhaps not too dissimilar to quaintly brutal British sports like The Ba’ Game in Kirkwall, or Uppies and Downies and Workington. It’s a local tradition for brothers Taira (Yagira) and Shota (Murakami), but Taiya has taken his quest for battle further. A lot further. He roams the local streets and shopping arcades, picking fist-fights with passers-by – apparently regardless of number, size or threat. Sometimes he wins. Mostly he loses. Yet there is something oddly honorable about him: he doesn’t attack women or kids, and seems to be looking to test himself against worthy opponents.

In the film’s defense, it’s possible this would have more impact if you’re familiar with the social setting and structures. For instance, part of the backdrop is the “battle of the portable shrines”, which is an actual thing, a historical remnant of institutionalized violence – perhaps not too dissimilar to quaintly brutal British sports like The Ba’ Game in Kirkwall, or Uppies and Downies and Workington. It’s a local tradition for brothers Taira (Yagira) and Shota (Murakami), but Taiya has taken his quest for battle further. A lot further. He roams the local streets and shopping arcades, picking fist-fights with passers-by – apparently regardless of number, size or threat. Sometimes he wins. Mostly he loses. Yet there is something oddly honorable about him: he doesn’t attack women or kids, and seems to be looking to test himself against worthy opponents.

That isn’t the case for Yuya (Suda), who sees Taiya in action and becomes an instant fan and imitator – only without the moral scruples. He’ll attack anyone, and his influence drags Taiya down with him. They end up kidnapping a young woman (Komatsu), and driving off with her, while Shota tries to track down his missing sibling. You get the idea this is all very much intended to be social commentary. Except, to a Western audience, it’s inevitably largely going to be shorn of that aspect – and, therefore much of its impact – because of the significant differences in culture. Though it appears we do have one thing in common: when faced with violence, modern bystanders here and there are both far more likely to whip out their cellphones and start recording, than attempt to intervene.

The violence is, I must admit, painfully realistic, sterilized of almost all cinematic trappings. Even the audio replaces crisp sound effects, with a wet, pulpy slap, and the camera observes from a safe distance, much like the onlookers. The media laps it up, and the film could have provided a pointed satire on the resulting publicity, along the lines of Natural Born Killers. Instead, after the kidnapping, the story seems to lose any real focus. While the subsequent violence becomes more intimate and personal, it is also less affecting: maybe because it’s something we’ve seen before, maybe because it’s more obviously “fake.” When I reached the end, I wasn’t sure what the intended message was – or even if a lack of message was the message.

One thing about which I am certain, however: this is definitely not the most extreme 108 minutes in Japanese cinema history. Set your expectations accordingly.