Rating: C

Dir: Robert Spafford

Star: Yvonne Buckingham, John Drew Barrymore, Alicia Brandet, Mel Welles

a.k.a. The Keeler Affair

“The movie they tried to ban” is a common advertising ploy used by B- and exploitation movie makers, with the aim of generating interest in potential viewers. This might be prurient, or might simply be people who react to being told they can’t watch something, by wanting to see it. How much truth there are in these claims does vary: I typically want to know who exactly are “they”, and what precisely did they try and do? But in the case of this low-budget slice of cheesecake, the claim is solidly justified.

“May I have an assurance that no film dealing with the life of Miss Keeler will be allowed to be shown in this country?” asked Member of Parliament Irene Ward in the House of Commons on November 21, 1963. [It’s amusing to see the broad spectrum of other questions, that day, which also included paraffin-vending machines, fire prevention in bingo halls and witchcraft] While the government response was quite restrained – it “would depend on whether the film was obscene” – the BBFC showed no such moderation, dropping the hammer even before the film was made.

“May I have an assurance that no film dealing with the life of Miss Keeler will be allowed to be shown in this country?” asked Member of Parliament Irene Ward in the House of Commons on November 21, 1963. [It’s amusing to see the broad spectrum of other questions, that day, which also included paraffin-vending machines, fire prevention in bingo halls and witchcraft] While the government response was quite restrained – it “would depend on whether the film was obscene” – the BBFC showed no such moderation, dropping the hammer even before the film was made.

Then BBFC secretary, John Trevelyan, wrote to producer John G. Nasht five months prior to Ward’s question, responding to Nasht’s proposed treatment by saying, “I can hold out no hope that a film made from this treatment… would be granted any form of certificate by this Board.” Despite this, Nasht ploughed ahead, though the film ended up having to be shot in Denmark. It was duly completed and sent to Trevelyan in December. If nothing else, the BBFC’s subsequent, highly dismissive response was entirely consistent with its earlier warning.

“An almost continuous picture of sordid vice, including sexual perversion, and is, in the opinion of this Board, morally objectionable… Even extensive cutting would not produce a satisfactory solution, since there are several scenes, which have some importance in continuity of narration, which would be completely unacceptable… There is no point in your pursuing the matter with this Board.”

Despite that, a second attempt was made in October 1969. At this time, Keeler’s memoirs were being serialized in the News of the World. Rights to the film had been sold on, and the new owners sought to exploit her increased profile for their subject. However, by that point, the BBFC President had become Lord Harlech, who had previously served with the scandal’s chief victim, John Profumo, in the government. While standards with regard to content had relaxed over the preceding six years, the result was still the same, Trevelyan writing, “Lord Harlech has asked me to tell you that he does not feel able to agree at the present time to the issuing of a certificate for this film.”

An attempt by the owners to do an end-run and get certification from the Greater London Council instead proved no more successful. The film was screened once at the New Cinema Club, a nomadic private film club (hence its ability, like the Scala, to screen uncertificated movies) run by Derek Hill, who’d go on to be film buyer at Channel 4 from 1981-1995. But it would not be until more than a quarter-century from the film’s original submission, that most Britons would finally be allowed to see a cinematic treatment of events, in the considerably higher-budgeted Scandal.

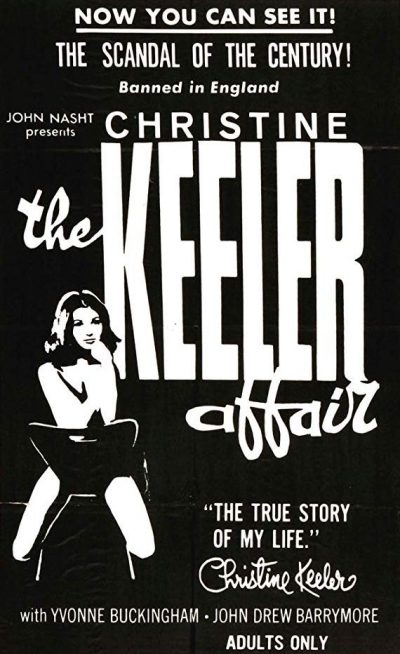

The first thing to say is that the poster (above right) is not actually exploiting the iconic photograph of Keeler straddling a chair. Because that picture was originally taken by Lewis Morley for the publicity purposes of the film, before being leaked to the Sunday Mirror and becoming part of sixties pop culture – as well as the poster for Scandal. [The chair used, amusingly, now forms part of the collection of the V&A Museum in London, having also played host to the bums of David Frost, Joe Orton and Dame Edna Everage]

The photo is certainly more memorable than the film, which makes a brave stab at being an earnest slice of social drama disguised as (very) soft-porn, but in the end, fails to be either. While much was made of Keeler’s appearance, this consists entirely of a few seconds at the beginning and end, as shown at the top. And in terms of political impact, it’s particular weak beer. All that’s seen of Profumo is his legs (!), hovering over Keeler at a pool party, though he is mentioned by name later. But I guess, this was a considerably fragiler time, in terms of political sensitivities to sex scandals.

It’s much more about the relationship of Keeler (Buckingham) with Stephen Ward (Barrymore – Drew’s Dad, to be specific!), the society osteopath/artist/pimp who took her under his wing. He turned her from a showgirl into, eventually, the 19-year-old girlfriend of Profumo, then a Cabinet Minister under Prime Minister Harold McMillan. Which wouldn’t necessarily have been a problem on its own: fellow minister Ernest Marples was into far weirder shit than banging teenage totty. But Keeler was also palling about with Captain Yevgeny Ivanov (Welles), a Russian diplomat.

The potential security problems resulting from the Secretary of State for War sharing vajayjay with a Soviet naval attaché don’t need spelling out. Rumours eventually started to circulate, following a case where another of Keeler’s lovers – she got around a bit – fired gunshots at her front door. Profumo initially proclaimed to parliament, “There was no impropriety whatsoever in my acquaintanceship with Miss Keeler.” However, after the truth was revealed, he was forced to resign, and Ward subsequently committed suicide while being tried for living off the immoral earnings of Keeler and pal Mandy Rice-Davies (Brandet).

This is most successful when Spafford abandons a straight narrative approach that largely plays like bad soap-opera. For example, the general structure is some kind of “dream court” in which Keeler is being tried, and its unusual enough to be interesting. Or there are the stylized goons (above) who accompany dodgy property mogul, Peter Rachman, when he meets her. [Rachman, like Ward, was dead by the time the film came out, so was unable to sue for any libel in his portrayal] Most striking is the upper-class party attended by Ward and Keeler, where the rest of the guests are mannequins (below), a nice bit of class critique. Shame the film didn’t thoroughly embrace this surreal approach.

Instead, it’s a rather maudlin affair, with Keeler a perpetual victim, forever being manipulated by Ward, and falls well short of Barrymore’s belief it is “a modern cross between Svengali and Pygmalion.” To 21st-century eyes, it’s just a depressing depiction of an abusive relationship, Ward consistently demeaning her: “You’ll never be a prostitute, Christine. You haven’t the mentality.” Though at least this aspect has aged better than some elements. For instance, we learn that if you smoke marijuana, within seconds you apparently need to have hook up with the first black man you find. Reefer Madness wasn’t just a thirties thing, I guess.

But it has a couple of oddly poignant moments too, such as Keeler’s friend telling her, prophetically, “All you’ve got is your face and what goes with it. And believe me, that won’t be so saleable a few years from now.” This perhaps counts as accidental social commentary, reflecting the limited opportunities which women had to make something of their lives in the early sixties. Ironically, part of the reason why the BBFC refused to grant it a certificate was they considered it “grossly unethical” for its release potentially rewarding Keeler financially. Maybe she should just have got a job in a flower-shop.

On the whole, though, it fails to shed any real light on the affair, and ends up being dull and amateurish. Witness the lengthy padding sequence of jazz go-go dancing – three and a half minutes, which feels more like thirty. Or the far too frequent use of newspaper headlines, etc. in lieu of actual narrative. Like most banned films, its reputation is considerably in excess of its impact, and it’s hard to see why anyone would be so bothered by this, as to demand its suppression.

For more information on the struggles of the film with British censors, please see Richard Farmer’s article in the Journal of British Cinema and Television, which inspired me to find and review the movie.