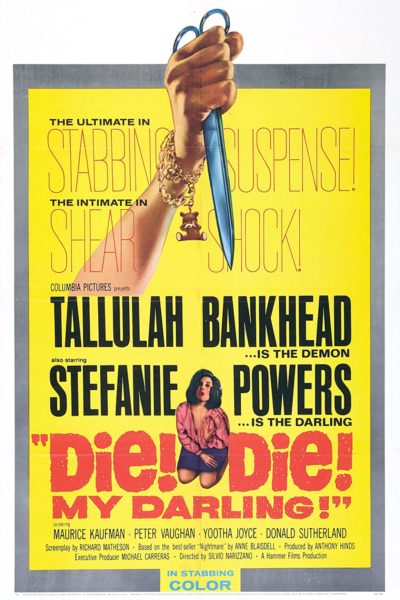

Rating: B+

Dir: Silvio Narizzano

Star: Tallulah Bankhead, Stefanie Powers, Peter Vaughn, Yootha Joyce

a.k.a. Die! Die! My Darling!

I have to say, this is one case where the alternate American title – a line spoken by Bankhead towards the end – does a better job of capturing the film’s spirit. The British title is a rather bland one. Part of the ongoing single-word theme for their psycho thrillers Hammer seemed to have going on, it just doesn’t do the escalating lunacy justice. There’s something to be said for the “psycho-biddy” genre, when it lets a veteran actress let rip, with absolutely no fucks being given, and the star here certainly does that, with a vengeance.

Bankhead plays Mrs. Trefoile, an old woman whose love for her late son, Stephen, who was killed in a car accident, is exceeded only by her religious fervour. Patricia Carroll (Powers), Stephen’s former girlfriend, an American who is now back in Britain, pays a courtesy visit to Mrs. Trefoile. Disturbed by her hostess’s beliefs – for example, that marriage being only “till death do us part” is dangerously liberal thinking – Patricia reveals she wasn’t intending to marry Stephen anyway. Big mistake. Before you can say “Lipstick? That’s the devil’s phallus!”, the guest finds herself locked up and being forced to see the error of her ways, at the hands of Mrs. Trefoile.

This could be seen as a cautionary tale about the dangers of tolerance. While a Yank, Patricia achieves remarkably British levels of politeness, quietly acquiescing to Mrs. Trefoile’s fundamentalist view of the world, which would make the Taliban shuffle awkwardly in their turbans. Personally, I would be making excuses about having to catch the bus, almost immediately, on hearing her describe Stephen with lines like, “I can only rejoice that he died unblemished. A virgin soul. So much more beloved by the Almighty.” Certainly, when my request for a looking-glass is rebuffed thus: “Mirrors are naught but tools of vanity, Patricia. I know. Vanity, sensuality, Patricia. The Bible speaks of our vile bodies.” And this is less than fifteen minutes in. It only goes downhill from there.

This could be seen as a cautionary tale about the dangers of tolerance. While a Yank, Patricia achieves remarkably British levels of politeness, quietly acquiescing to Mrs. Trefoile’s fundamentalist view of the world, which would make the Taliban shuffle awkwardly in their turbans. Personally, I would be making excuses about having to catch the bus, almost immediately, on hearing her describe Stephen with lines like, “I can only rejoice that he died unblemished. A virgin soul. So much more beloved by the Almighty.” Certainly, when my request for a looking-glass is rebuffed thus: “Mirrors are naught but tools of vanity, Patricia. I know. Vanity, sensuality, Patricia. The Bible speaks of our vile bodies.” And this is less than fifteen minutes in. It only goes downhill from there.

Of course, horror movies are largely dependent on people being oblivious to warning sings, something we discussed as recently as last week. It allows the audience to feel superior to the inhabitants, I suspect. And once the trap is sprung, there’s not much poor Patricia is able to do. If it had just been the elderly Mrs. Trefoile, it might have been different. But there’s also the husband-and-wife pair of driver and housekeeper, Harry (Vaughn) and Anna (Joyce), both of whom have no qualms about getting physical when necessary. It’s weird to see them pre-fame, as the actors would go on to greater recognition in seventies sitcoms: Vaughn in Porridge and Citizen Smith, and Joyce in Man About the House and George & Mildred. Here, truth be told, she’s kinda hawt. Especially when wrestling about on the floor with Powers. Oops. Did I say that out loud?

A couple of other familiar faces pop up. Benny Hill regular Henry McGee gets a very brief role as the local rector. But the biggest name is Donald Sutherland, three years before becoming famous in The Dirty Dozen. Here, he plays the retarded gardener who lumbers around, providing further muscle when needed. But it’s Tallulah’s show, and she’s quite glorious to watch in her final role, gradually becoming more and more unhinged. She seems, in particular, to have something against the colour red: woe betide Patricia when her lipstick is noticed, being told “Go and remove that filth at once.” It’s the little things that make the difference here; witness her underplayed reaction later, when Patricia’s boyfriend, Alan (largely useless, until the end), drives up in a red Mini.

[In post-production, Bankhead had to come in and redub one bit of dialogue: “And so Patricia, as I was telling you, that deluded rector has in literal effect closed the church to me.” The process apparently took eight hours to capture the single line, not least because she turned up drunk.]

Director Narizzano was making his feature debut, though he had a lot of experience in television. Not much of it was in horror though, and some of the time, especially in the early going, there’s a bit of a jarring feel. Scenes are apparently played for comic relief, when they shouldn’t be, and Wilfred Josephs’s score doesn’t help in that matter, being far too “Whoops! Where are my trousers?” The direction is at its most effective when it simply sits back, and lets the actors do their bit – Bankhead in particular, though the central performances are all rather good. The script was written by Richard Matheson, in his first work for Hammer, based on Anne Blaisdell’s novel, Nightmare. It hits all the expected spots, though I’ll confess to hoping for a more drastic conclusion, in keeping with the fire and brimstone antagonist.

It does make some pointed stabs at religious hypocrisy, with those who most loudly profess their faith, often being the ones least suited for a place in heaven. Yet there’s also Mrs. Trefoile, caught by Patricia fawning over scrapbooks from her days as an actress, describing that world: “He led me from that evil… A pit of evil. A place for the lost and the damned. The devil’s entertainment. God’s anathema. It is a painful memory to me.” Given Bankhead’s rather dubious reputation in golden age Hollywood – the Hays Committee listed her among the actresses they considered “unsuitable for the public”, after she proclaimed “I haven’t had an affair for six months. Six months!” – the irony is obvious.

There can be little arguing that Bankhead delivers one of the top five performances – indeed, perhaps even the best – by anyone other than Peter Cushing or Christopher Lee in a Hammer film. From the very beginning, Mrs. Trefoile is a coiled spring of religious obsession, and she only gets more tightly wound as things progress. This is Tallulah’s world: everyone else is just living in it.

This review is part of Hammer Time, our series covering Hammer Films from 1955-1979. Also, check out Trav SD’s great guide to the Psycho-biddie genre.