“When people finish their day and hurry home, my day starts. My diner is open from midnight to seven in the morning. They call it “Midnight Diner”… I make whatever customers request as long as I have the ingredients for it. That’s my policy. Do I even have customers? More than you would expect…”

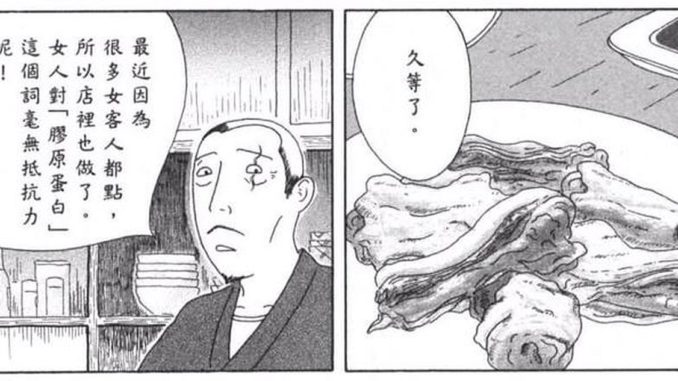

The above doesn’t exactly sound like the kind of Japanese content I like. Where is the arterial spray? Where are the giant moths? Where is the pinky violence? Yet the TV series whose episodes begin with the above, gentle introduction has become one of our firm favourites. What it does have in common with my more usual tastes, is being an adaptation of a manga: Shin’ya Shokudō by Yarō Abe, which began its run in Big Comic Original in 2006. Three years later, it was adapted into a 10-episode TV series for the MBS network.

So what is it about? A late-night mini-restaurant/bar, tucked away in a Shinjuku back-alley, run by a man whom everyone calls Master (Kaoru Kobayashi). No-one kn0ws much about his background, but he has a scar on his face which gives him a definite “Do not fuck with” air. Into his establishment come a broad range of characters, including strippers, gangsters, other bar owners, cops and office ladies. He treats everyone the same: politely, but without deference. The interactions between them – as well as the dishes he cooks and they eat, which give each episode its name – are the heart of the stories which unfold.

So what is it about? A late-night mini-restaurant/bar, tucked away in a Shinjuku back-alley, run by a man whom everyone calls Master (Kaoru Kobayashi). No-one kn0ws much about his background, but he has a scar on his face which gives him a definite “Do not fuck with” air. Into his establishment come a broad range of characters, including strippers, gangsters, other bar owners, cops and office ladies. He treats everyone the same: politely, but without deference. The interactions between them – as well as the dishes he cooks and they eat, which give each episode its name – are the heart of the stories which unfold.

It’s a simple premise, yet one which allows for almost infinite variation. Some are comedic, other tragic, or simply dramatic. The Master is the only person to be in every episode, and acts as something between a bar-tender and a priest. He never judges – neither does the show – yet you can sense his reactions of approval or otherwise to his customers behaviour. It is all very character-driven, yet its understated approach is thoroughly engaging. We were left wishing there was a place like that near us, where we could go and hang out. As well as with a strong hunger for octopus wieners, the chosen food at the diner of Yakuza boss and regular customer, Ryu.

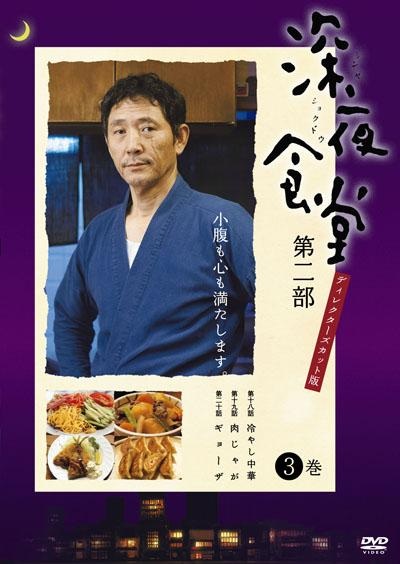

After the first three seasons, Netflix stepped in as a producer, and that’s when the show began to receive attention outside of Eastern Asia. The fourth season was released in 2016, without much fanfare in the West, as Midnight Diner: Tokyo Stories, which is where we caught on to its pleasures. The fifth season followed, described as the second season of Tokyo Stories. Yet in June, Netflix also quietly released the first three series, as Midnight Diner. This succeeded in confusing the hell out of us. Fortunately, it’s not a show where you particularly need to watch the seasons in order: while supporting cast members drift in and out not a great deal changes over time.

There have been a number of spinoffs. South Korea’s was called Late Night Restaurant; China had one in 2017, also called Midnight Diner, but that flopped, getting the lowest-ever audience score for a show. This may partly explain why the Chinese movie adaptation, relocated to Shanghai and starring Tony Leung Ka-fai as the Master, sat on the shelf for two years, until finally sliding out with little fanfare last September. There have also been two Japanese films, and below, you’ll find reviews of all three of those feature versions.

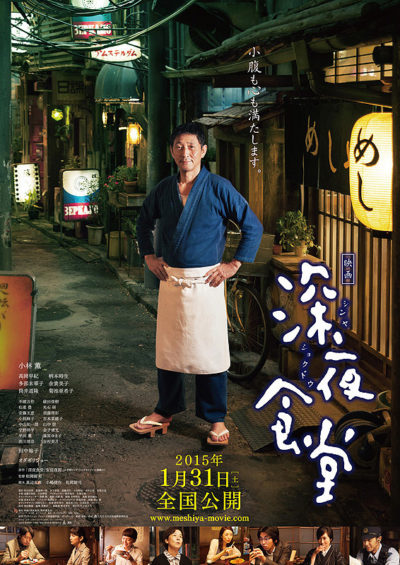

Midnight Diner (2014)

Rating: B-

Dir: Joji Matsuoka

Star: Kaoru Kobayashi, Saki Takaoka, Mikako Tabe, Michitaka Tsutsui

I was curious to see how a movie version of this beloved Japanese TV show would work. The answer is… Not particularly differently. Indeed, despite its two-hour running time, this might as well be four episodes of the series combined. We do get to see a little bit more – in particular, what the Master does when he’s not running his Shinjuku diner [I always thought he lived above the shop: turns out that’s not the case], and even some acknowledgement of events in the outside world. But if you’re expecting anything cinematic, or revelations about the origin of the Master’s scar, you’re going to be disappointed, because Matsuoka seems resolutely intent on playing it safe. If you like the series, you are probably going to like the movie – and for the same reasons.

We get four tales about the Master (Kobayashi), and the customers that come into his little restaurant. The first is a slight entity, about a “kept woman”, Tamako (Takaoka), who has been thrown down on her luck, after the death of her sugar daddy. It ends before it has achieved much impact. The second sees the Master dealing with a homeless girl, Michiru (Tabe), who does a “dine and dash” only to be subsequently overcome with guilt. He sees potential in her honesty, and takes Michiru under his wing, helping her rebuild a life. The third story sees a refugee from Fukushima (Tsutsui), who lost his wife in the tsunami, come to Tokyo in search of a rescue worker for whom he has developed feelings, who may not share them. And wrapping around these, is an urn of funeral ashes left in the diner. This apparently happens quite a lot, because the prices for burial plots in Japan are sky-high. Who knew?

We get four tales about the Master (Kobayashi), and the customers that come into his little restaurant. The first is a slight entity, about a “kept woman”, Tamako (Takaoka), who has been thrown down on her luck, after the death of her sugar daddy. It ends before it has achieved much impact. The second sees the Master dealing with a homeless girl, Michiru (Tabe), who does a “dine and dash” only to be subsequently overcome with guilt. He sees potential in her honesty, and takes Michiru under his wing, helping her rebuild a life. The third story sees a refugee from Fukushima (Tsutsui), who lost his wife in the tsunami, come to Tokyo in search of a rescue worker for whom he has developed feelings, who may not share them. And wrapping around these, is an urn of funeral ashes left in the diner. This apparently happens quite a lot, because the prices for burial plots in Japan are sky-high. Who knew?

The strength remains the excellent performances, in particular Kobayashi, whose stoic good-nature provides the moral glue which holds everything together. You get the sense he may have seen the worst in people over the years, yet still seems to believe in their innate goodness, which is quite heart-warming. The second story is probably the best, not least because, for once, the Master is at the center of proceedings – he’s usually the one holding the coats, so to speak. Though I was a little weirded out by how the subtitles on the Hong Kong DVD suddenly switched into Scottish brogue for a bit. I eventually figured out it was an attempt to convey Michiru’s rural origins, far from Tokyo. Credit for the thought, rather than the execution.

While all the stories are still worthwhile, and fans of the show will enjoy the little nods paying homage to what they have already seen, it feels as if this is a case where less is more. The lack of a fixed running-time may have given the creators greater freedom, but this seems to have simply led them to meander about. The Fukushima chapter, in particular, feels like it could have been told in half the time, with little or no reduction in impact. If I’d paid theatrical prices for this, I might have been slightly annoyed at being left still hungry.

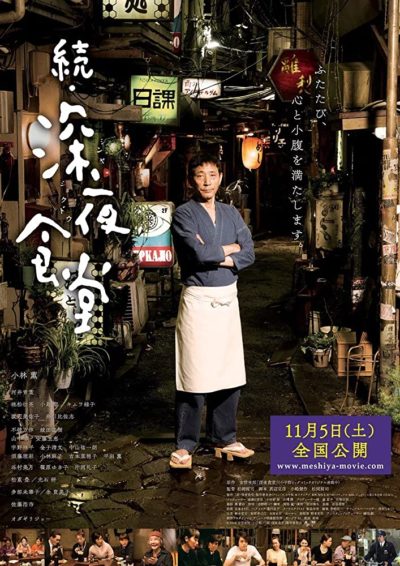

Midnight Diner 2 (2016)

Rating: B

Dir: Joji Matsuoka

Star: Kaoru Kobayashi, Aoba Kawai, Midoriko Kimura, Misako Watanabe

I don’t know why they didn’t call this, Midnight Diner: Second Helpings. But, I suppose, that would be rather too crass and obvious for a show which is the epitome of subtle and understated. As with its predecessor, it feels rather more like multiple episodes of the television show packaged into an omnibus edition, rather than being a specific cinematic entity. However, I’ve come to the conclusion that’s not necessarily a bad thing. It’d be, to use an appropriate metaphor, like the chef of a favourite restaurant changing his recipes after opening an extension to the premises.

So, what we get here are three stories, with a vaguely funereal theme – it begins with the “regulars” at the titular establishment congregating and discovering they have all been to various funerals and wakes. That is, except for Noriko (Kawai), a publishing house editor who dresses like she has been to a funeral, because she enjoys the reactions it provides. [The bar’s resident pervert proclaims, “Men can’t resist a woman in mourning”] However, after she has to attend a genuine funeral, she meets a man who is interested in more that funeral weeds. Or is he? The second segment concerns Seiko (Kimuta), owner of a nearby restaurant and her struggles with her son, who is seeking his own way. He doesn’t want to follow in the family business, and his girlfriend is an older woman, whom his mother refuses point-blank to meet. Except, little does Seiko know, she’s already friends with her son’s intended.

So, what we get here are three stories, with a vaguely funereal theme – it begins with the “regulars” at the titular establishment congregating and discovering they have all been to various funerals and wakes. That is, except for Noriko (Kawai), a publishing house editor who dresses like she has been to a funeral, because she enjoys the reactions it provides. [The bar’s resident pervert proclaims, “Men can’t resist a woman in mourning”] However, after she has to attend a genuine funeral, she meets a man who is interested in more that funeral weeds. Or is he? The second segment concerns Seiko (Kimuta), owner of a nearby restaurant and her struggles with her son, who is seeking his own way. He doesn’t want to follow in the family business, and his girlfriend is an older woman, whom his mother refuses point-blank to meet. Except, little does Seiko know, she’s already friends with her son’s intended.

The third and final entry was, for me, the most successful. It illustrates one of the central tenets of the series: that people are basically good, and will help each other when needed. The beneficiary is Yukiko, an elderly woman who travels to Tokyo after falling for a scam, handing over two million yen to her supposed son’s employer. Except, does she really have a son, or is this a symptom of dementia? Because, she seems to know very little about her child. Still, the customers of Master’s restaurant rally round to help – not least, Michiru, who sees a chance to “pay it forward”, after Master helped her in the previous movie. This section does a beautiful job of being warm-hearted, without toppling over into sentimentality.

The Master (Kobayashi) does perhaps take a bit more of a back seat than in the first film. But he remains the glue who holds things together, overseeing the customers in a way that’s no-nonsense, yet welcoming [I suspect good reason exists why there is never even the slightest inkling of trouble, despite its late hours of operation – even when the Yakuza boss isn’t in the place]. It’s the kind of place I wish existed around the corner from Film Blitz Towers. Though if it did, I’m not sure I’d get much sleep, since we’d probably be in there, every night, from midnight until 7 am… Now, if you’ll excuse me, I have a craving for noodles.

Midnight Diner (2019)

Rating: C+

Dir: Tony Leung Ka-Fai

Star: Tony Leung Ka-Fai, Tony Yang, Jiao Junyan, Vision Wei

It was with some trepidation that we settled in for this. We’ve seen enough American remakes of foreign movies to know that even the good ones are generally superfluous, tending more to copy strengths than address weaknesses. To be honest, that is largely the situation here. Yet, I’m happy to settle for a decent Chinese copy, which is respectful of the source and ends up being not all that far short of as good as the Japanese movies – if still not quite managing to capture the essence of the TV series. Much credit to Leung, especially considering this was his feature debut. If he isn’t Kaoru Kobayashi, he captures much the same quiet strength and firm compassion. He also knows that while the nameless man who runs the late-night restaurant may be at the core of the film, he isn’t what it’s about.

Indeed, in the early going, this felt like it could be capable of surpassing the Japanese movies, with a combination of lush cinematography capturing Shanghai at night, and some effective writing. The first section is particularly good, about a boxer (Yang), whose “horrible mother” is forever interfering in his life. I was hoping the film might break with tradition, and devote its full running-time to this story. It doesn’t, and the rest of the film struggles somewhat to recapture the early promise. There are moments: for example, we learn where Chef (as he’s called here, rather than Master) got the scar on his face, something which had always puzzled us. But there is also an unconvincing love story between two customers, one a taxi-driver, the other a wannabe model; and another segment even drops in that cliche, familiar from TV movies, of a random fatal illness. Really? Even though it’s handled as well as it could be, we expect better.

Indeed, in the early going, this felt like it could be capable of surpassing the Japanese movies, with a combination of lush cinematography capturing Shanghai at night, and some effective writing. The first section is particularly good, about a boxer (Yang), whose “horrible mother” is forever interfering in his life. I was hoping the film might break with tradition, and devote its full running-time to this story. It doesn’t, and the rest of the film struggles somewhat to recapture the early promise. There are moments: for example, we learn where Chef (as he’s called here, rather than Master) got the scar on his face, something which had always puzzled us. But there is also an unconvincing love story between two customers, one a taxi-driver, the other a wannabe model; and another segment even drops in that cliche, familiar from TV movies, of a random fatal illness. Really? Even though it’s handled as well as it could be, we expect better.

What it does nicely, is translate the characters into ones which are perhaps more appropriate to the Chinese setting. Rather than the Greek chorus of three salary ladies, we get a trio of young advertising types. Initially, they’re befuddled by the notion that a place exists which doesn’t have wifi; then they taste Chef’s cooking, and become regulars. I’d probably prefer to have learned more about them, or the old guy sitting next to the cop in the corner. This works best when it’s in the diner, and the further it strays from there, the more it becomes just another sappy romantic drama, without anything to separate it from all the other sappy romantic dramas. It’s still going to make you hungry – another difference we noticed is the copious amount of stir-frying done here, no doubt reflecting local tastes. But the preponderance of romance in the stories eventually causes this cinematic meal to become a bit overcooked. Just as the best food isn’t made from a single ingredient, a greater variety of flavors would probably have been a good thing, and left us wanting more.