Rating: B

Dir: Terence Fisher

Star: Peter Cushing, Susan Denberg, Thorley Walters, Robert Morris

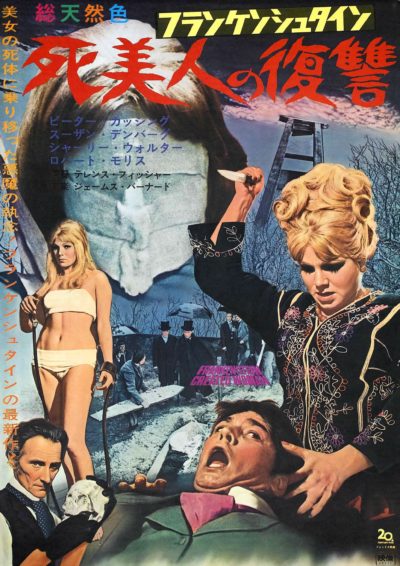

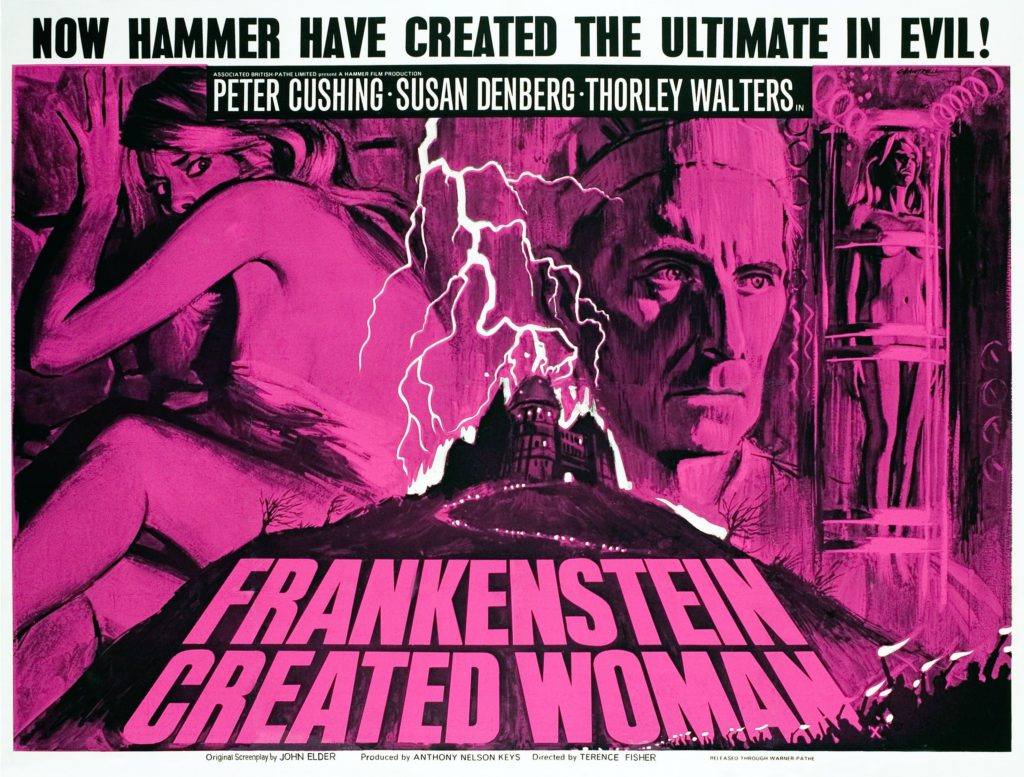

The fourth film in Hammer’s Frankenstein-chise goes in a rather different direction from its predecessors, and is all the better for it, I think. Instead of simply offering another rehash of life being created, the science being investigated by Baron Frankenstein (Cushing) is more soul-centric. In fact, there’s a good case to be made for the title being inaccurate, since Frankenstein doesn’t “create” any females here. And, in particular, at no time is anyone seen sporting the bikinis shown on the poster. Many such publicity stills exist, but the “creation” sequence depicted was never filmed. This has not stopped me from using said advertising materials, naturally.

The woman of the title is Christina Kleve, crippled daughter of a local landlord. One night, she’s being taunted by a trio of local young toffs, when her boyfriend and the Baron’s assistant, Hans (Morris), comes to the rescue. However, when the landlord is killed by the toffs, suspicion falls on Hans, whose father was guillotined for murder. After a travesty of justice, Hans suffers the same fate, and a distraught Christina flings herself from a bridge to her doom. Both corpses, conveniently, end up with Frankenstein and his partner, Dr. Hertz (Walters).

If life gives you lemons, make lemonade. And if life gives you two corpses, one separated at the neck… Well, clearly you transfer Hans’s soul into Christina’s body. When she wakes up, she is now perfect, thanks to the surgical knowledge of the Baron. She’s also blonde and has no recollection of the past. Though despite her new, male soul, Christina v2.0 is still remarkably adept with hair and make-up, as Chris pointed out. Unless the Baron has mad makeover skills or something, in addition to his medical abilities.

If life gives you lemons, make lemonade. And if life gives you two corpses, one separated at the neck… Well, clearly you transfer Hans’s soul into Christina’s body. When she wakes up, she is now perfect, thanks to the surgical knowledge of the Baron. She’s also blonde and has no recollection of the past. Though despite her new, male soul, Christina v2.0 is still remarkably adept with hair and make-up, as Chris pointed out. Unless the Baron has mad makeover skills or something, in addition to his medical abilities.

In what has to be considered as a very poorly-considered “experiment”, the Baron takes Christina/Hans on a surprise trip to see the guillotine. The resulting psychic shock triggers a split, with Hans now commanding Christina to take revenge on the three young men who bullied her, and committed the murder for which Hans was executed. After the first couple of bodies, even the authorities are growing concerned, and suspect Frankenstein, whose local reputation is perilously close to black magic. He figures out what has happened and – after a scene featuring what I’m going to call Parkour Cushing – rushes off to try and stop her from further murder or self-harm.

It feels like a while since the last Cushing entry (it was She), and it’s good to have him back. For Peter is on top form here, taking absolutely no shit from anybody, least of all the locals. When, during Hans’s trial, he’s accused of dabbling in the dark arts, his reply is acerbic: “To the best of my knowledge, doctorates are not awarded for witchcraft. But in the event they are, no doubt I shall qualify for one.” Better yet, this terse exchange towards the end, when he tries to explain the situation to authorities.

Police officer: Do you take us for fools?

Baron Frankenstein: Yes.

This may be as close to a mic drop as Cushing ever achieved.

It’s a shame Playboy model Denberg’s career was so brief, lasting just two years, covering only one other film and three TV episodes (albeit including Star Trek, where she appeared in “Mudd’s Women”). Per the IMDb, “After becoming immersed in the 60s high life of drugs and sex, Denberg left show business and returned to Austria,” which is as good a reason to quit as any, I guess. I especially liked her performance here as Christina v1.0, where she puts over an enormous amount of vulnerability. Though, as seems quite common for Hammer lead actresses of the period, her voice was dubbed over in post-production. Jane Merrow replaced her, according to Hammer Horror #5.

Coming as this does on the heels of the iconic Racquel Welch in One Million Years B.C., it appears to follow a trend of gradually ramping up the sexuality, which Hammer were exploring in this period. While still some way from anything as overt as they’d reach in the seventies, the presence of a centrefold as a major member of the cast is definitely indicative of the loosening attitudes in society around this time. I mean, we even get to see two characters in bed! And with each other! Somehow the British Empire did not crumble as a result. But there’s also Christina v2.0 getting all slinky in pursuit of her victims, and Denberg nails it:

Spoilers follow. Learning more about Denberg’s post-movie history definitely lends a poignancy to the movie finale, for in real-life she reportedly had a mental breakdown and ended up working as a topless waitress in an adult cinema. While some of the factors were self-inflicted, e.g. her drug habit, she certainly seems to have been abused and exploited by some of the men in her life, and that reflects Christina’s fate here. With her mission of revenge accomplished, Hans goes back into her psyche, leaving Christina v2.0 to deal with the guilt of what she has done. She can’t, and for the second time, plunges into a river to her death. Whether it was the toffs bullying her, the Baron experimenting on her, or Hans controlling her, Christina could be considered a victim of masculinity at its most toxic. It was, indeed, the beasts that killed the beauty…

[November 2010] While this was not Hammer’s first foray into horror where the “monster” was a woman – see also things like The Gorgon – it predates by four years their full-blown 1971 trilogy of such things. I liked this one. It has a metaphysical bent and more thoughtful air, definitely different from the usual “lumbering monster rampage” we’d seen in other entries. There’s also something particularly disturbing about Hans being trapped in a woman’s body, and coming on to other men for revenge purposes. Never mind murder: following through and sleeping with them, then announcing who s/he really is would probably be more traumatic.

Worth noting, the Baron is just about innocent here, and not responsible, directly, for anyone’s death. Indeed, when he realizes what is going on, Victor tries to warn the locals, and when they (somewhat understandably) don’t believe him, sets off to stop Christine/Hans himself. If there are gaps in the narrative e.g. why Frankenstein is apparently unable to use his hands, this is a highly-enjoyable combination of horror and romance, with some surprisingly deep philosophical tones to enhance the flavour. B

This review is part of Hammer Time, our series covering Hammer Films from 1955-1979.