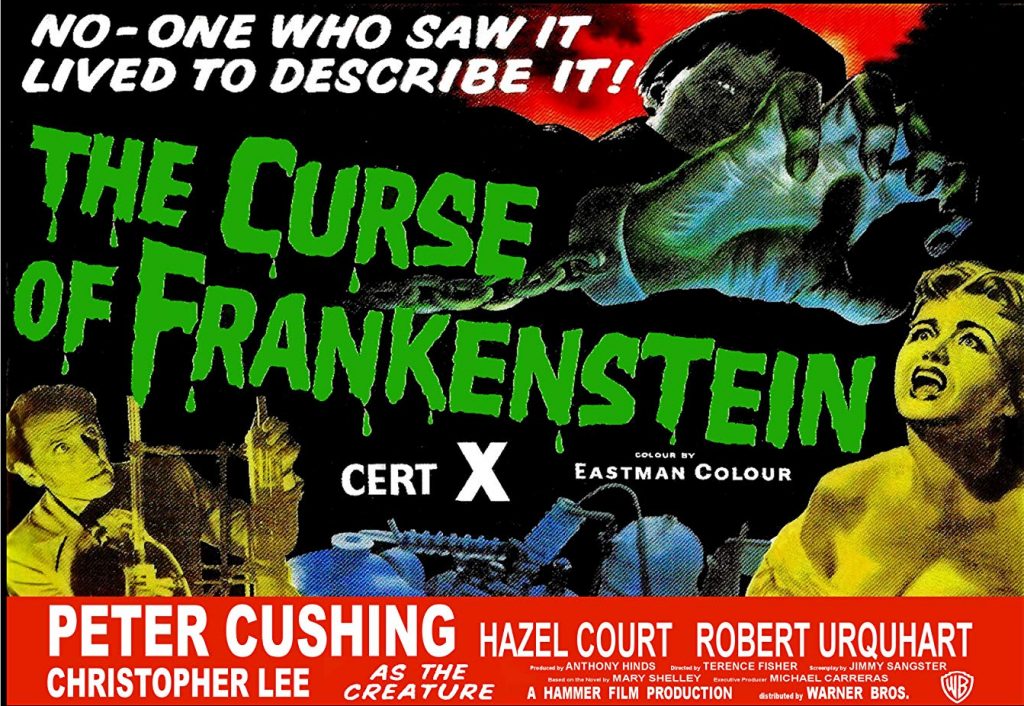

Rating: B

Dir: Terence Fisher

Star: Peter Cushing, Robert Urquhart, Christopher Lee, Hazel Court

On May 2nd, 1957, everything changed for the horror genre and the British film industry. On that day, The Curse of Frankenstein was released, a landmark movie which set Hammer up for 15 years of world domination. It was not initially the critical and cult icon it has since become: closer at the time to I am Legend than Hereditary, being a huge commercial success while receiving scathing reviews. I suspect Hammer were more than happy with it skewing thus way. But some of those critics… Most infamous among them was C.A. Lejeune of The Observer who proclaimed it, “Among the half-

The idea of a Frankenstein adaptation had originally been suggested to Hammer by producer Max Rosenberg and writer Milton Subotsky, the latter having come up with a script. The studio basically said, “Thanks, good idea – we’ll take it from here,” and got Jimmy Sangster to write his own script. Rosenberg and Subotsky only received $5,000, and went off to start Amicus Films instead. The big problem was, of course, that Universal had made the Frankenstein adaptation, and jealously guarded it. While Mary Shelley’s book was public domain, any elements unique to the Universal version, such as the iconic look of the monster, were verboten. Which may be why Sangster’s script concentrates so much more on the Baron [Everyone knows Boris Karloff in the 1931 version. Far less famous is Colin Clive as his creator]  Cushing was well-known in the UK for his television work. He had been Mr Darcy in an adaptation of Pride and Prejudice, and became particular fanous in 1954 for playing Winston Smith in Nineteen Eighty Four, adapted by Quatermass creator Nigel Kneale. That provoked a motion in parliament condemning the BBC for pandering “to sexual and sadistic tastes”, so any complaints about Frankenstein were hardly unfamiliar territory for Cushing. As the monster, Hammer went with Christopher Lee, though almost used long-time Carry On stalwart Bernard Bresslaw instead. But, reportedly, he wanted £10 a day, while Lee would do it for £8. And, as they say, the rest is history. This wasn’t their first film in common: both were in Lawrence Olivier’s 1948 Hamlet, though not together. Cushing was Osiric, while Lee went uncredited as a guard.

Cushing was well-known in the UK for his television work. He had been Mr Darcy in an adaptation of Pride and Prejudice, and became particular fanous in 1954 for playing Winston Smith in Nineteen Eighty Four, adapted by Quatermass creator Nigel Kneale. That provoked a motion in parliament condemning the BBC for pandering “to sexual and sadistic tastes”, so any complaints about Frankenstein were hardly unfamiliar territory for Cushing. As the monster, Hammer went with Christopher Lee, though almost used long-time Carry On stalwart Bernard Bresslaw instead. But, reportedly, he wanted £10 a day, while Lee would do it for £8. And, as they say, the rest is history. This wasn’t their first film in common: both were in Lawrence Olivier’s 1948 Hamlet, though not together. Cushing was Osiric, while Lee went uncredited as a guard.

It’s Cushing’s performance which holds the film together. His portrayal of a driven scientist, unrestricted by moral governors, remains the seminal depiction of the character, unmatched in over sixty years. As he’d do so often, Cushing sells his lines with a conviction which makes the audience accept what he’s saying. Take this speech: “As for revolting against nature, haven’t we done so already and succeeded? Isn’t the thing that’s dead supposed to be dead for all time? Yet we brought it back to life. We hold in the palms of our hands secrets that have never been dreamed of. Where nature puts up barriers to confine the scope of man, we’ve broken through! There’s nothing to stop us now.” I defy anyone to listen to him deliver it without nodding your head and thinking, “Well, he’s got a point.”

This makes the Baron not an unlikable character, despite being a bit of a bastard to just about everyone. He rejects the advice of his best friend, Dr. Paul Krempe (Urquhart). He’s unfaithful to his fiancee, Elizabeth (Court), though in his defense, it’s a kinda weird relationship. First of all, she’s his cousin. Secondly, it’s a long-time arranged marriage, and you wonder why he agrees to let her move in, when he’s banging the maid, Juatine (Valerie Gaunt). Why have a cow delivered, if you employ a pint of milk? Er, or something. Continuing a theme we saw in X: The Unknown, the slutty Justine has a much more noticeable foreign accent than the chaste Elizabeth, and meets a bad end after threatening to expose the Baron’s activities. Though she does give us our first sighting of the renowned Hammer Gothic nightie.

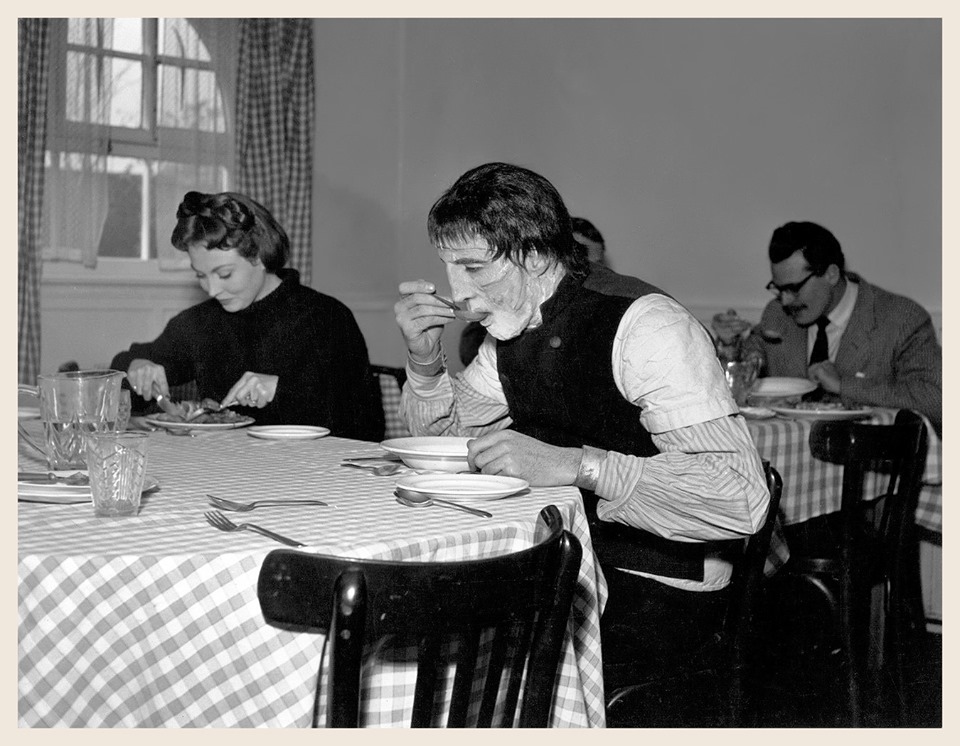

Let’s talk about the fashion sense generally. I was amused by the Baron’s eschewing a laboratory coat, and instead wearing a laboratory sports jacket (or 19th-century equivalent thereof), which becomes steadily more stained over the course of the film. But the peak of sartorial elegance belongs to the creature (Lee). When we first see him, he’s wrapped in bandages. But in his very next scene, after escaping, he has on a fetching, colour-coordinated ensemble, of a shirt and suit (above). All of which fit his monstrous frame very well, so it’s not as if he could have swiped them from the Baron. Was there a branch of BigClothing4U conveniently open in Engelstadt?

Let’s talk about the fashion sense generally. I was amused by the Baron’s eschewing a laboratory coat, and instead wearing a laboratory sports jacket (or 19th-century equivalent thereof), which becomes steadily more stained over the course of the film. But the peak of sartorial elegance belongs to the creature (Lee). When we first see him, he’s wrapped in bandages. But in his very next scene, after escaping, he has on a fetching, colour-coordinated ensemble, of a shirt and suit (above). All of which fit his monstrous frame very well, so it’s not as if he could have swiped them from the Baron. Was there a branch of BigClothing4U conveniently open in Engelstadt?

Generally, though, the film still looks and sounds great. The first Frankenstein adaptation in colour, this stands out in particular in the laboratory scenes. These are an all-you-can-eat buffet of bubbling flasks, dry ice and gadgetry, more decided by what looks good than any apparent scientific necessity. And Fisher is always willing to let us appreciate the way things are. For example, the Baron and Paul’s first resurrection unfolds without dialogue or music, just ambient sound, for over three minutes. That’s a director who is confident in the skills of his cast and crew, and their ability to hold the audience’s attention.

Of course, it all inevitably goes wrong, with the Baron’s creation far from the best of all parts. He blames Paul for the brain damage, after a struggle in the lab. Though after you’ve pushed a visiting scientist off a balcony, head-first onto a parquet floor, to get that brain, you’ve probably already voided its warranty. By the end, the Baron is locked up in jail, awaiting execution for murder because all evidence of the monster has gone, and Paul, the only person to have seen it and lived, has disavowed any knowledge. Probably because there are some things with which mankind was not meant to meddle. Little wonder Cushing looks like Hugh Jackman after a week-long bender.

Despite poor reviews, the movie was a massive success, single-handedly bringing back the genre of Gothic horror from the dead, and beginning its cycle anew. In just one week at one American cinema, it grossed $72,000, at a time when the average movie ticket cost 62 cents. That’s close to 40% of the film’s estimated budget of £65,000. And with that, Hammer were off to the races.

This review is part of Hammer Time, our series covering Hammer Films from 1955-1979.

Original review: Things Not To Say To A Mad Scientist, #43: “I know plenty, if I care to tell.” And, if you do, probably best not to follow up with, “If you don’t marry me, I’ll tell!” Yeah. No prizes for guessing the fate of the maid who uses those two lines on Baron Victor Frankenstein (Cushing). An up-close and personal meeting with his creation (Lee), who has already shown homicidal tendencies and was shot by the Baron’s assistant Paul Krempe (Urquhart), though Victor simply dug up the monster and re-resurrected him. Paul deeply disapproves of Victor’s efforts to create artificial life, and only hangs around because he wants to protect Elizabeth (Court), the Baron’s fiancée and cousin. She is blissfully ignorant – to the point of idiocy, it seems to me – regarding exactly what her husband-to-be is doing, during all those hours spent in his “stuffy laboratory”. Mind you, she’s also ignorant of his dalliances with the maid, so let’s be honest, perception is not Elizabeth’s strong suit. Eventually though, her curiosity gets the better of her, after the lab door has been left unlocked after an argument between the Baron and Paul.

The monster – who was nearly played by Carry On‘s Bernard Bresslaw, if you can believe it – is a sideline here. This is about the ethical struggle between Victor, dedicated to the exclusion of all else, and his “conscience”, in the form of Krempe. The former believes that scientific exploration should know no bounds, while the later takes the view that there are some things with which mankind should not meddle. It’s an malleable ethical line Paul draws; seems ok to re-animated things which were dead, but he refuses to help with Victor’s plans to create life. That said, the final scene, where Paul has a chance to help his mentor out of a nasty, guillotine-shaped situation, results in an interesting moral choice by him. Both leads are very solid in their performances, and one can only imagine the impact on a late 1950’s cinema crowd. You can, however, see why many regard this as the definitive version of the Shelley classic, moving the focus squarely back from the monster to its creator and emphasising the Gothic elements.

[November 2010]