Rating: C+

Dir: Joseph Losey

Star: Macdonald Carey, Shirley Anne Field, Oliver Reed, Alexander Knox

a.k.a. These Are the Damned

This is an odd beast, to say the least, and very difficult to get a good handle on. Visiting American tourist Simon Wells (Carey) picks up the tarty Joan (Field), only to find out quickly it’s a scam, as he is mugged by her brother, King (Reed) and his gang of teddy-boys. But Joan is sick of her life and, encountering Simon on his boat later, opts to sail off with him, much to King’s disapproval. He and his crew chase after the pair, and they end up on cliffs, near a mysterious remote facility run by Bernard (Knox), a scientist who refuses to talk about his work, which appears to involve a group of nine children kept in isolation. While clambering on the cliffs, Simon, Joan and King all find themselves joining the children, who keep them hidden from Bernard and his soldiers, though there is no apparent way of escape. An uneasy alliance is formed, with the aim of somehow rescuing the captive children from Bernard’s capture, and whatever he may have had planned for them.

This feels almost like two films spliced into one, and the first half is more concerned about the relationships of the various characters – even those that turn out to be of little relevance to proceedings when they unfold – and is pretty feeble viewing. Once everyone gets to the research center, things warm up considerably. The makers would have been better off condensing events until that point into about five minutes, and perhaps telling more about the society the kids have created in their isolation; they’re rather more polite and well-spoken than The Lord of the Flies, shall we say. One thing I really did appreciate was the bleakness apparent here; normally, Hammer movies went for the triumph of good over evil, true love conquering all, etc. Not wanting to give too much away, let’s just say that doesn’t quite take place here. The results are just about unique – not only in the Hammer canon, also in the realm of sixties sci-fi as a whole – and merit a look, despite its turgid opening.

[November 2010]

This was an adaptation of one of only two novels written by H.L. Lawrence, The Children of Light. It was quite a quick turnaround for Hammer: the book came out in 1960, and the script was submitted to the BBFC the following April. Though it was more than another two years before it got a UK release, in May 1963, despite the year attached to it by the IMDb. America had to wait even longer, until July 1965, because Mike Frankovich, boss of co-production partners Columbia, hated it. Even then, the version eventually distributed had been cut by 17 minutes. Though, depending on which minutes were removed, the editing might have made for a better product. Especially if it was those involving Veronica Lindfors’s sculptor, who never seems to serve any significant purpose to the story.

This was an adaptation of one of only two novels written by H.L. Lawrence, The Children of Light. It was quite a quick turnaround for Hammer: the book came out in 1960, and the script was submitted to the BBFC the following April. Though it was more than another two years before it got a UK release, in May 1963, despite the year attached to it by the IMDb. America had to wait even longer, until July 1965, because Mike Frankovich, boss of co-production partners Columbia, hated it. Even then, the version eventually distributed had been cut by 17 minutes. Though, depending on which minutes were removed, the editing might have made for a better product. Especially if it was those involving Veronica Lindfors’s sculptor, who never seems to serve any significant purpose to the story.

Probably the main difference from the source material is that, in the book, Simon is a killer, on the run having murdered his wife after discovering her unfaithfulness. It’s not clear if the change was in the original script, as director Losey required that to be rewritten before filming began. That wasn’t the only issue he caused the company. Losey had been run out of Hollywood due to his ties with and sympathy for the Communist party, and had moved to Europe to continue directing, albeit often under a pseudonym. He had directed a short feature for the company, A Man on the Beach back in 1955, and was originally due to direct X – The Unknown for Hammer. Ill-health supposedly forced him to pull out, though as we discussed, a clash with star Dean Jagger is also rumoured.

On this production, Losey ended up going £25,000 over budget – no small amount for the studio – and additional scenes had to be shot by Anthony Hinds to clarify the ending, which remains vague on a number of points even with the extra footage. Losey’s transformation of the novel into a dire warning about the threat of nuclear proliferation appears to be regarded more warmly now than it was at the tine. While Michael Carreras spoke well of the director’s talent, albeit perhaps without having seen the end result (“The film, I’m sure, was a very good film”), it was not a commercial success, making it probably unsurprising that Losey wasn’t asked back.

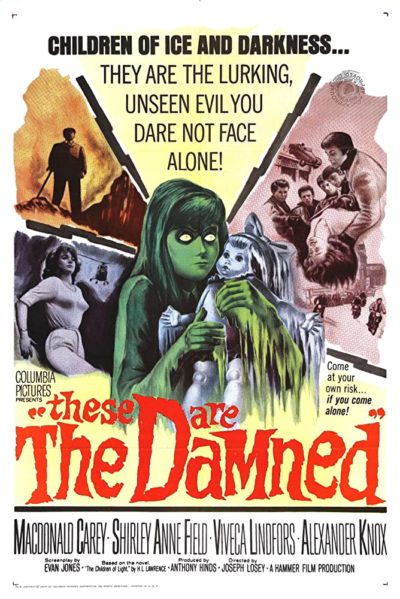

The changed title seems to imply a connection to the similarly “weird children” themed Village of the Damned, released in 1960 – something not exactly actively denied by the poster! But here, the kids are much more victims than antagonists. Another potential influence might have been A Clockwork Orange, whose novel by Anthony Burgess first came out the previous. King and his gang, with their “uniform”, fondness for violent behaviour and music, do seem to foreshadow Alex and his droogs in Kubrick’s classic work of a decade later, though obviously, this is more of a sidelight in this film. What hasn’t lasted so well is the relationship between Simon and Joan, which certainly doesn’t adhere to the “half plus seven” rule. At the time of shooting in 1961, Carey was 48, and looked it; meanwhile, Joan’s character explicitly says she is 20, and looks it too. Can’t say I blame King for getting pissed-off.

The changed title seems to imply a connection to the similarly “weird children” themed Village of the Damned, released in 1960 – something not exactly actively denied by the poster! But here, the kids are much more victims than antagonists. Another potential influence might have been A Clockwork Orange, whose novel by Anthony Burgess first came out the previous. King and his gang, with their “uniform”, fondness for violent behaviour and music, do seem to foreshadow Alex and his droogs in Kubrick’s classic work of a decade later, though obviously, this is more of a sidelight in this film. What hasn’t lasted so well is the relationship between Simon and Joan, which certainly doesn’t adhere to the “half plus seven” rule. At the time of shooting in 1961, Carey was 48, and looked it; meanwhile, Joan’s character explicitly says she is 20, and looks it too. Can’t say I blame King for getting pissed-off.

It still seemed as curiously disjointed as it did when watched a decade ago: even Chris, unprompted, said that it felt to her like two different movies. I definitely preferred the direct science-fiction aspects, and the presence of a government who’d stop at nothing to cover up its secrets, has not exactly become less plausible over the decades since. There’s also something plaintive about the kids – whom, I just realized, are all named after famous English kings and queens – who are completely innocent with regard to their innate lethality e.g. a pet rabbit becoming “sleepy”. I just can’t help wondering what the pre-Losey version of the script was like, and whether it might have resulted in a more coherent whole.

This review is part of Hammer Time, our series covering Hammer Films from 1955-1979.