Rating: C+

Dir: Elmo Williams

Star: Beverly Michaels, Thora Hird, April Olrich, Paul Carpenter

a.k.a. Blonde Bait

Hammer doing a women-in-prison film? Yeah, this comes as a bit of a surprise, being a little outside their usual genre niche. However, in the first half of the fifties, these had been something of a trend, with a number of successful entries in the United States. 1950’s Caged, starring Eleanor Parker and Agnes Moorehead, became a breakout success, even netting Parker a Best Actress Oscar nomination. Among the WiP films which were made over the following years was Betrayed Women (1955), starring Michaels; it may well have been the impetus which drove Hammer to hire her for this, though she was fairly well-established generally as a blonde femme fatale. As with The Quatermass Xperiment, having an American star would likely help sell the end result across the Atlantic. Though, as well see, a major overhaul also took place.

Michaels plays showbiz artiste Angie Booth, who is in a relationship with the shadily uncertain Nick (Carpenter), who continually pops off for long periods on mysterious errands. But this time, he swears that when he comes back in three months, he’ll marry Angie, and arranges to meet her at the Oxhead Inn on New Year’s Eve. However, Angie’s Svengali-like mentor, Julian Lord, takes unkindly to this, and in the ensuing fight she slugs him with a heavy mirror. Angie gets six months for assault, meaning she’ll be seeing in the New Year through prison bars. Her only chance is to escape, which she does during a Christmas concert with the help of long-term inmate, Gran (Hird). The pair are joined by Spanish inmate Margueritte (Olrich), who is desperate to stop her baby from being forcibly taken away. Will Angie be able to dodge the resulting dragnet and make her rendezvous? And even if she does, will Nick show?

It’s amusing to think of an alternate universe where this took off for Hammer, rather than the horror genre. Would they then have put out a steady stream of women-in-prison films for the next two decades? Must admit, I do kinda want to see their version of the Ilsa trilogy, starring Ingrid Pitt… But reality had different plans. This instead largely sank without trace on its April 1956 release, to the extent I couldn’t even find an image of the UK poster, or the trailer. From the point of view of subsequent WiP films, it is naturally extremely tame, with no sex to speak of, and the violence limited to the struggle between Angie and Julian. The sections set in the prison feel more like an episode of seventies TV series, Within These Walls.

The main element in its favor is Michaels, appearing in the final feature role before retiring from acting at the grand old age of 28. She towers over most of the cast, both in terms of charisma and literal size (she was 5’9″; at the time, the average woman was about five inches shorter). We saw Hird briefly in Quatermass, but she gets a lot more to do here, and you can see why she’d go on to win three BAFTAs through her TV performances. In a smaller role as her irascible pal. Grace, is Hermione Baddeley, who’d be Oscar-nominated a couple of years later for Room at the Top. Indeed, director Williams already had an Academy Award on his mantelpiece, albeit as an editor on High Noon.

Rather less effective are the supporting cast, and the attempts at comedic interludes are painfully unsuccessful. For example, the woman serving a sentence for bigamy, who has both of her husbands coming to visit. Maybe this was amusing in the fifties? And a lot of the other attitudes have not aged well either. Witness lines such as, “Like most women in prison, I’m here because of a man,” or the even more androcentric one by the warden, after Angie tearfully requests compassionate leave for New Year’s Eve: “I didn’t expect this hysteria. Is it a man?” But perhaps the most shocking moment is Gran taking care of Margueritte’s child: baby in one hand, cigarette in the other!

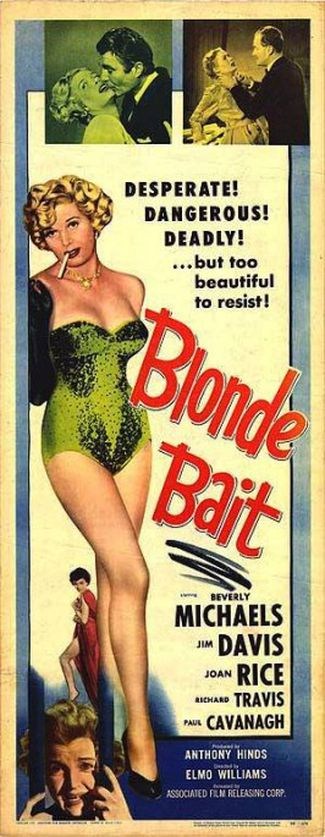

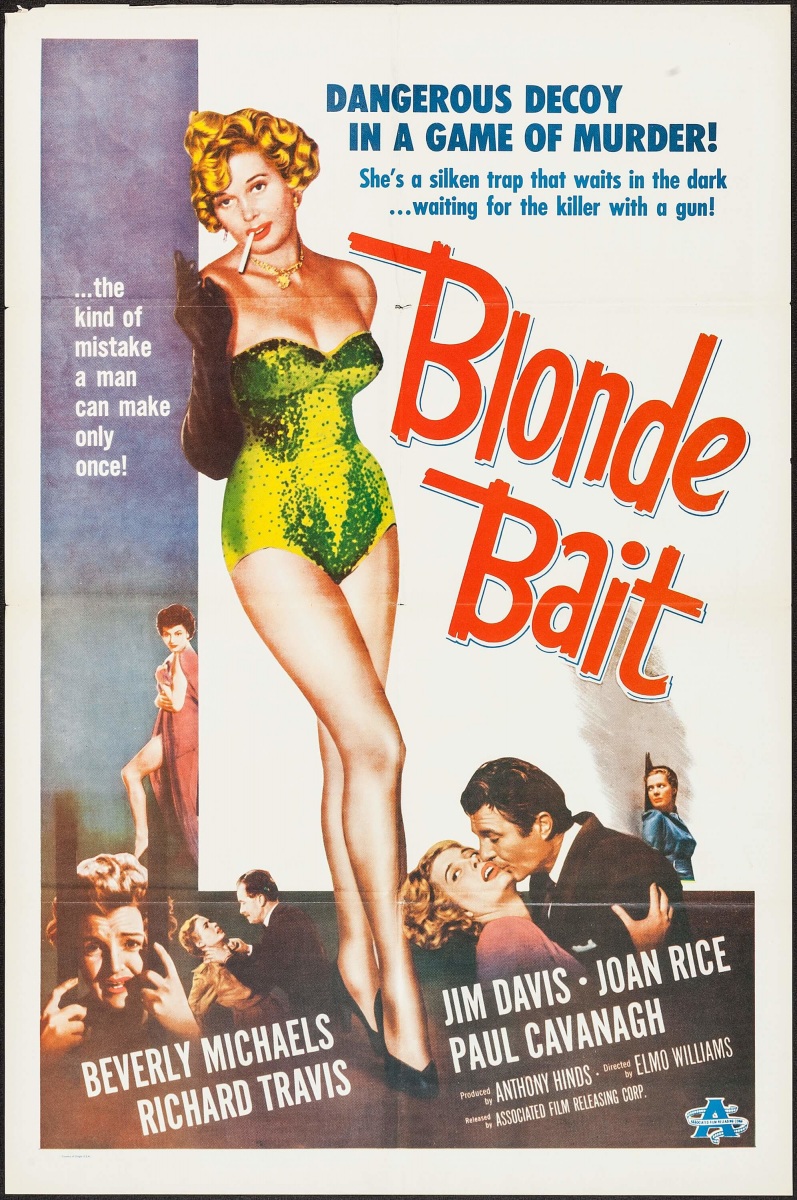

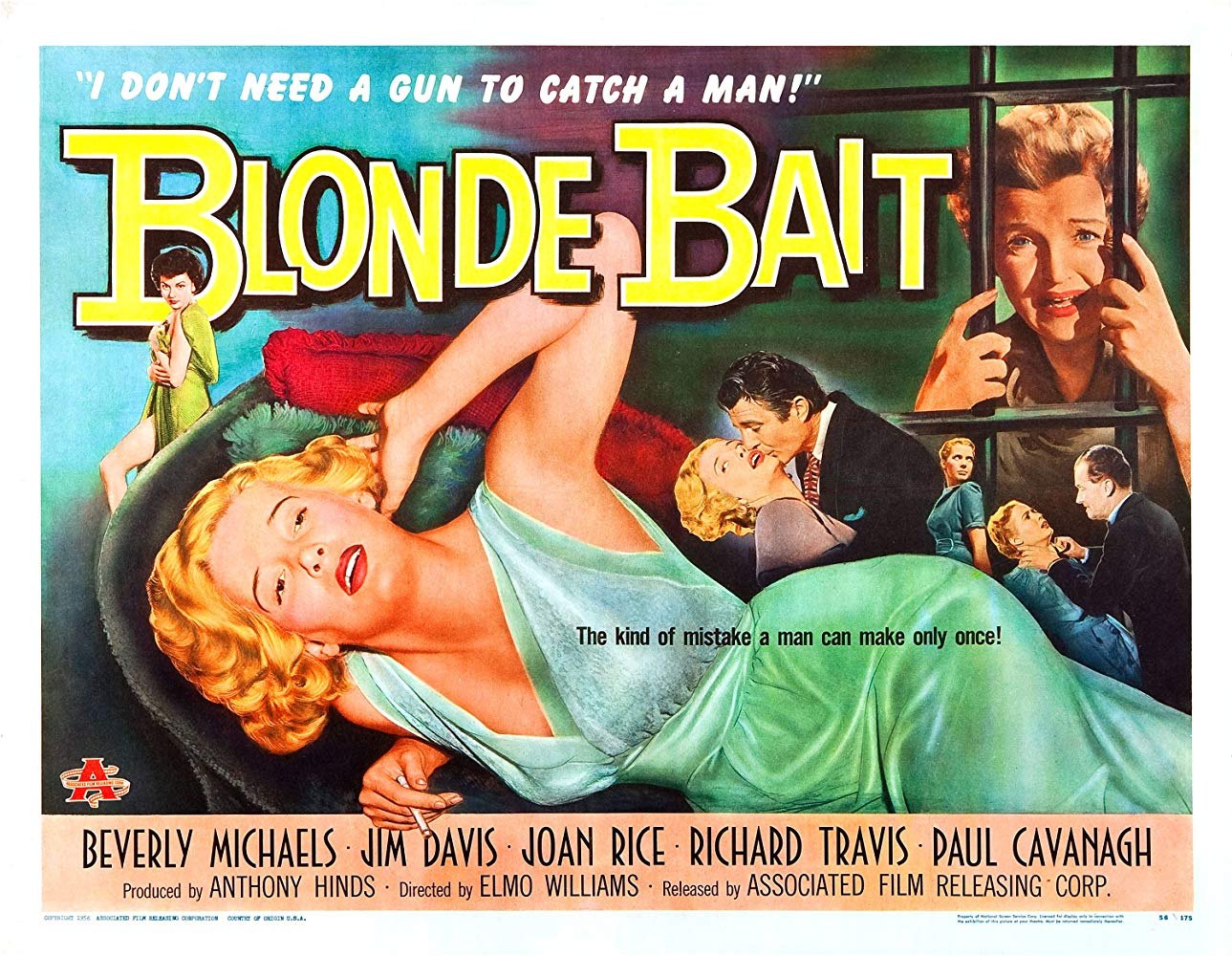

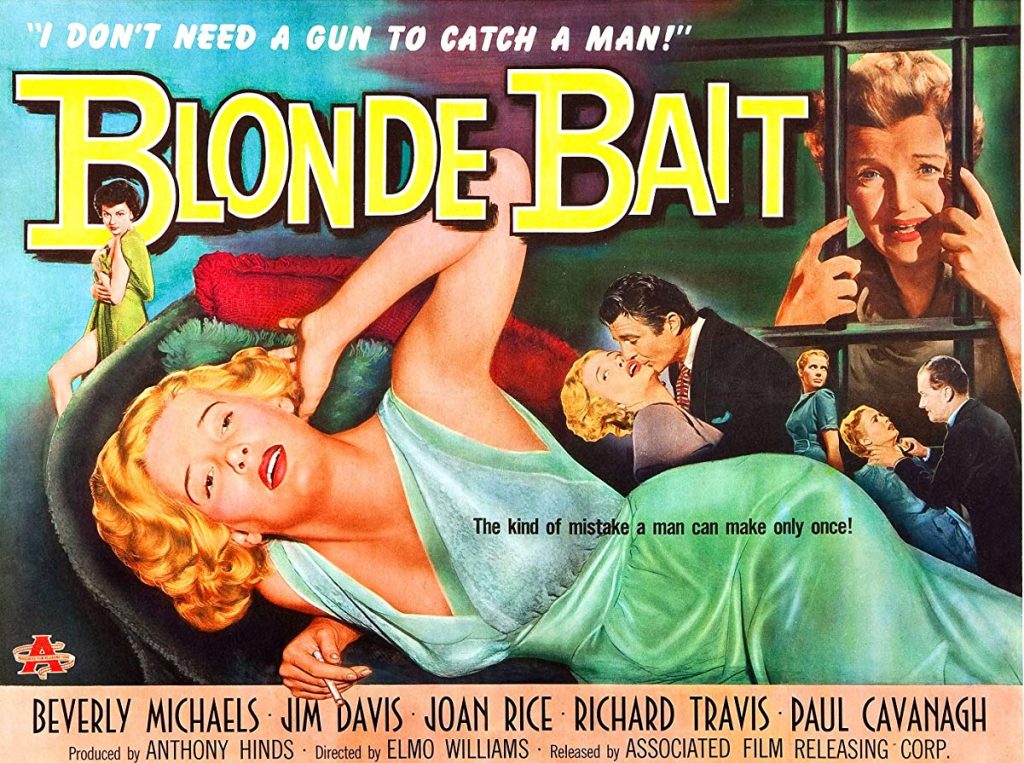

In case you didn’t recognize it, above is the poster for the American release of the film. Most obvious is the title change: and it’s not the first Hammer film to go fishing for an audience across the pond with different “bait”. While it precedes coverage here, The Last Page, Hammer’s 1952 noir starring Diana Dors and their first feature directed by Terence Fisher, was re-titled Man Bait for American consumption. But the changes here were considerably more than cosmetic. Additional footage was shot, completely reworking the story and making highly significant changes to it.

Firstly, Nick is played by an entirely different actor, Jim Davis (the future Jock Ewing in Dallas) replacing Carpenter. There’s also much less ambiguity about his absences. Courtesy of a brand-new character, US State Department agent Kent Foster (Richard Travis), we learn that Nick is a former Nazi collaborator, now a courier for a spy ring, who also murdered one of Kent’s colleagues. He has so far escaped justice, but Kent devises a cunning plan to catch his target. With the help of the warden and stool-pigeon Gran, they’ll dupe Angie into an “escape”, then follow her to the rendezvous, and take Nick down. However, keeping the three escapees under surveillance, without tipping Angie off to their subterfuge, is not that easy.

Obviously, this is a major modification, and requires a lot of additional footage. Michaels does appear in some, particularly the book-end sections with Nick. The opening is considerably more… smoochy than the British version. The ending, on the other hand, is considerably less happy – particularly for Nick. If the results are, unsurprisingly, clunky on occasion, it works surprisingly well, considering their drastic nature. Most significantly, it addresses a major weakness of Women: the ease with which Angie is able to waltz out of jail. It also reins back some of the annoying comic-relief mentioned above, which I heartily endorse.

On balance, I marginally prefer the American cut. Its pacing is improved, and making Nick a clear villain helps give better dramatic momentum to the escape and its aftermath. If you haven’t seen the original and didn’t know, you probably wouldn’t notice the joins.

This review is part of Hammer Time, our series covering Hammer Films from 1955-1979.