Rating: B

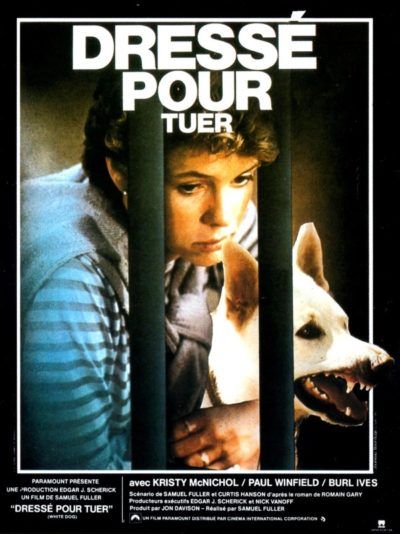

Dir: Samuel Fuller

Star: Kristy McNichol, Paul Winfield, Jameson Parker, Burl Ives

While I knew of director Fuller, about the only thing I could tell you about his work was the (possibly apocryphal) story of The Big Red One being seized by Manchester police during the video nasty panic, unaware it was a war movie. It would not be out of line for Fuller, whose films often proved controversial. White Dog was no different. In particular, the NAACP objected, even though the President of their Hollywood branch had been brought in by the studio to consult on the film. This was likely involved in Paramount’s decision to all but bury the film’s initial release – it grossed less than $50,000. The NAACP remained opposed several years later when Paramount sold it to NBC for television, a spokesperson saying, “We’re against the whole thrust of the film and what it says about racism.”

Quite why, it’s hard to see. If roughly as subtle as a brick to the back of the head, even if the water is muddied in a number of odd places, it’s no less obvious in its anti-racist message. It starts off looking like a Wonderful World of Disney movie, in which aspiring actress Julie Sawyer (McNichol) hit s stray German Shepherd in the Hollywood hills, and nurses it back to health. It even saves her from an intruder – though in one of those odd scenes mentioned above, the dog finishes watching a war movie before coming to the rescue. So far, so charming story the whole family can enjoy. Except, we then learn more than Julie, as we see the dog viciously savage the driver of a street-sweeper.

A further attack follows, and Julie learns the dog has been trained to go for black people on sight. Though, again, it seems not only black people; the animal also threatens her boyfriend (Parker), and the home invader is white too. She’s unwilling to have the dog – who’s never named, save an off-hand reference to “Mr. Hyde” – put down, though the advice Julie gets is that such behaviour cannot be unlearned. She eventually finds one trainer, Keys (Winfield), prepared to try, putting his own black skin on the line by becoming the dog’s sole source of food, in an effort to repair the damage. This is a rather radical departure from the novel by Romain Gary on which the film was based, where the trainer was a radical Black Muslim, who reprogrammed it to attack white people.

A further attack follows, and Julie learns the dog has been trained to go for black people on sight. Though, again, it seems not only black people; the animal also threatens her boyfriend (Parker), and the home invader is white too. She’s unwilling to have the dog – who’s never named, save an off-hand reference to “Mr. Hyde” – put down, though the advice Julie gets is that such behaviour cannot be unlearned. She eventually finds one trainer, Keys (Winfield), prepared to try, putting his own black skin on the line by becoming the dog’s sole source of food, in an effort to repair the damage. This is a rather radical departure from the novel by Romain Gary on which the film was based, where the trainer was a radical Black Muslim, who reprogrammed it to attack white people.

Yeah, it’s not exactly flying under the radar here, with the obvious question being asked as to whether racism is a question of “nurture or nature,” and if the former, whether it can be undone. By the time the credits roll, Fuller has made his opinions clear: haters gonna hate, though the target of that hatred is potentially subject to change. There, I’ve saved you ninety minutes. However, I’d not let that put you off watching the film, as it remains interesting, as much for Fuller’s pervasive cynicism. Julie represents, in short, the typical bleeding-heart liberal who wants to save everyone. The director does not agree, thinking there are some who simply cannot be redeemed, and society would be better off putting them down.

This belief is depicted with an undeniable talent, though it’s the work of an artist painting with a shotgun – albeit deliberately. If I had my doubts about the classification of this as horror going in, the attack scenes are very well-staged. Producers allegedly said they wanted the film to be “Jaws with paws”, and these sequences certainly deliver, and are a forceful reminder of why I’m a cat person. Hell, the mere close-up of its snarling face was enough for me. Five different German Shepherds were used in filming: I wonder if it was like the Seven Dwarves, with animals being switched in depending on the emotion required for the movie – and potentially named Happy, Sleepy, Grumpy, Waggy and Attacky.

Two scenes in particular stand out. One takes place after Keys has succeeded in getting the dog to accept him. The question is whether it will now accept any black person, and to that end, he brings in a pal to approach the animal, which is snarling ferociously – Keys stands nearby with a loaded gun at the ready. It’s an incredibly tense few minutes. The other sees Julie visited by an avuncular man, accompanied by his young grand-daughters… who turns out to be the man responsible for the dog’s racist training. The layers of meaning in this are startling, especially in comparison to the otherwise direct approach Fuller takes. It’s perhaps this depiction of a racist as an otherwise apparently “normal person” which helped bring down the wrath of the NAACP.

Much of the film was shot at the Wildlife Waystation animal sanctuary in Sylmar. It was run for over forty years by Martine Colette, who cameos in the movie as one of Keys’s neighbours. Colette, who died earlier this year, was basically The Tiger King before The Tiger King was a thing. She supposedly rescued animals, but became the target of myriad complaints from opponents who said she exploited her residents, breeding them for cute baby photo ops to make money. If entirely irrelevant to the movie, it’s quite the rabbit hole to go down, if you are curious.

Much of the film was shot at the Wildlife Waystation animal sanctuary in Sylmar. It was run for over forty years by Martine Colette, who cameos in the movie as one of Keys’s neighbours. Colette, who died earlier this year, was basically The Tiger King before The Tiger King was a thing. She supposedly rescued animals, but became the target of myriad complaints from opponents who said she exploited her residents, breeding them for cute baby photo ops to make money. If entirely irrelevant to the movie, it’s quite the rabbit hole to go down, if you are curious.

It’s another case where the eventual director was not the one originally slated for the movie. Roman Polanski was first in the frame, with Jessica Lange starring; his legal troubles, leading to an unscheduled (and ongoing) departure from the Unites States scuppered that. It was then intended to be Tony Scott’s directorial debut; Jodie Foster was also attached. All those alternates would certainly have been interesting choices. Fuller, meanwhile, never directed another movie in Hollywood again, and followed Polanski to France, saying this “would alleviate some of the pain and doubt that I had to live with because of White Dog.”

This article is part of our October 2022 feature, 31 Days of Classic Horror.