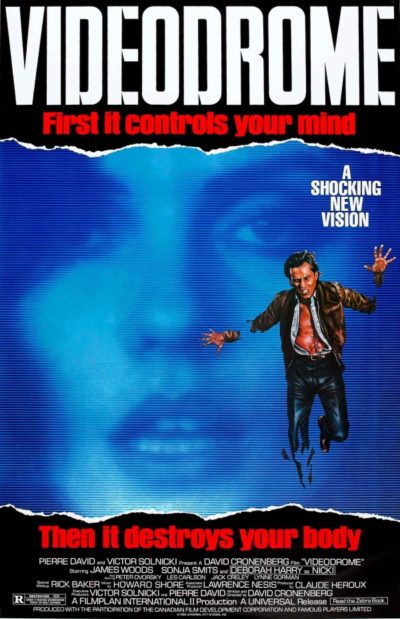

Rating: A+

Dir: David Cronenberg

Star: James Woods, Debbie Harry, Sonja Smits, Peter Dvorsky

People unclear on the concept: #629. Variety reported in April last year that “Universal Pictures will remake the 1983 David Cronenberg-directed thriller Videodrome, with Ehren Kruger set to write the script and produce with partner Daniel Bobker.” While bad enough by itself, things got worse: “The new picture will modernize the concept, infuse it with the possibilities of nano-technology and blow it up into a large-scale sci-fi action thriller.” What, you mean like Kruger’s other “large-scale sci-fi action thriller” script – Transformers 2: Revenge of the Fallen? Kill me. Kill me now. There hasn’t been much heard of the project since, and one hopes it founders in development hell, because it’s clear those involved with it haven’t got a clue. “Large-scale”? “Action”? I don’t think so. But let’s start at the beginning…

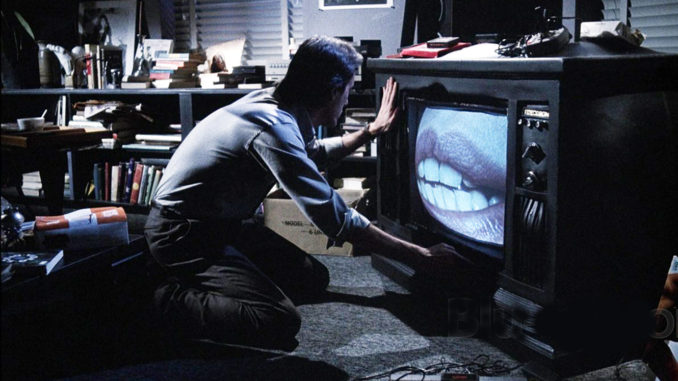

Max Renn (Woods) is a sleazy executive for Civic TV, a Toronro fringe TV station always on the lookout for extreme content that can pull an audience. His pet geek Harlan (Dvorsky) shows Renn pirated footage called ‘Videodrome’: “torture, murder, mutilation… It’s real sicko. For perverts only,” according to Harlan. Renn is intrigued, and wants to find the source, despite being warned off. Just as excited is Nicki Brand (Harry), a radio-show host with masochistic tendencies, who heads to Pittsburgh, the source of the signal. However, Renn finds himself increasingly plagued by bizarre hallucinations. Inanimate objects like his TV coming to life, and his body morphing, a slit developing in his stomach into which a handgun, carried by the now-paranoid Max, vanishes.

While defending Civic TV on another station’s chat-show, he encounters media pundit Brian O’Blivion, who exists only on television, and then O’Blivion’s daughter Bianca (Smits), who runs a hostel – the Cathode Ray Mission – which lets the homeless watch TV, to “help patch them back into the world’s mixing board.” The O’Blivions know the origins of Videodrome. Turns out – and this is clearly in the novelization than the film version – that it was an experiment in military tech gone wrong, causing tumours in the subjects and rendering them susceptible to mind control. Its current owners, under business magnate Barry Convex, intend to use Civic TV as a conduit, purging society of those who enjoy its degenerate programs. They now can control Renn, and he acts as their assassin. But Bianca has some counter-programming techniques of her own to turn Max against Convex.

While defending Civic TV on another station’s chat-show, he encounters media pundit Brian O’Blivion, who exists only on television, and then O’Blivion’s daughter Bianca (Smits), who runs a hostel – the Cathode Ray Mission – which lets the homeless watch TV, to “help patch them back into the world’s mixing board.” The O’Blivions know the origins of Videodrome. Turns out – and this is clearly in the novelization than the film version – that it was an experiment in military tech gone wrong, causing tumours in the subjects and rendering them susceptible to mind control. Its current owners, under business magnate Barry Convex, intend to use Civic TV as a conduit, purging society of those who enjoy its degenerate programs. They now can control Renn, and he acts as their assassin. But Bianca has some counter-programming techniques of her own to turn Max against Convex.

Even though it’s approaching thirty-years old, there is so much here that is still astonishingly relevant to our world, such as the melding of humanity and technology. The same goes for the bizarre pronouncements of Brian O’Blivion [modelled on Marshall McLuhan, who lectured at the University of Toronto while Cronenberg was a student there]. “Soon, all of us will have special names, names designed to cause the cathode-ray tube to resonate,” may not have made much sense at the time, but now… Screen-names, anyone? The same goes for “Television is reality, and reality is less than television.” Watching the movie now, I found myself going, “Oh, so that’s what he meant,” more than once. And then there’s Harlan’s rant: “North America is getting soft, patrón, and the rest of the world is getting tough. Very, very tough. We’re entering savage new times, and we’re going to have to be pure and direct and strong if we’re going to survive them.” In a post 9/11, Patriot Act world, that’s just chilling.

From a visual standpoint, the viewer is right there with Renn, as his reality melts out from underneath him, to the point where neither he nor we have a handle onto which we can hold any longer. In this way, it foreshadows Cronenberg’s later Spider, which also had a central haracter with a tenuous grip on reality, there through mental illness: in both, the audience is right there in it with them, and you can either go with it, or leave, because the director has no intention of letting you off his merry-go-round once it starts spinning. It helps, massively, that we have James Woods in the lead role: he takes a potentially-unlikeable character and makes him first human (he dips cold pizza in his morning coffee), then sympathetic. Yeah, he’s a sleazy smut-peddler who can’t afford the luxury of moral scruples: but you still get the feeling he’d be a good guy with whom to enjoy a cold beer or six.

From a visual standpoint, the viewer is right there with Renn, as his reality melts out from underneath him, to the point where neither he nor we have a handle onto which we can hold any longer. In this way, it foreshadows Cronenberg’s later Spider, which also had a central haracter with a tenuous grip on reality, there through mental illness: in both, the audience is right there in it with them, and you can either go with it, or leave, because the director has no intention of letting you off his merry-go-round once it starts spinning. It helps, massively, that we have James Woods in the lead role: he takes a potentially-unlikeable character and makes him first human (he dips cold pizza in his morning coffee), then sympathetic. Yeah, he’s a sleazy smut-peddler who can’t afford the luxury of moral scruples: but you still get the feeling he’d be a good guy with whom to enjoy a cold beer or six.

For tax reasons, the main shoot had to be completed by the end of 1981, and as a result, the script for the movie was still being altered during filming, with Cronenberg working on it almost the entire time. This may help explain why some aspects are underexplained – such as the weapon which fuses with Renn’s hand, being a ‘cancer gun’ which fires tumours at its target. However, this kind of thing doesn’t hurt the movie much; indeed, it may be the reverse, since logical flaws simply help enhance the feeling that the world in which it operates has no rules. Yet surprisingly often, it also shows a sense of black humour. Much of this comes from Woods’ reactions as things unfold, which sell the weirdness in a very human way. The first time he encounters a video-tape that breathes, he drops it to the ground – but then prods it gingerly with his toe, the way we would a dead rat, to check if it was really gone. It’s an amusing, and appropriate, response, typical of the desert-dry wit and Max Renn’s down-to-earth approach, even as things fall apart.

The imagery put onto the screen as this happens is some of the most startling ever, and utterly disproves the theory that it’s always better to ‘use your imagination’ when it comes to horror. Because your imagination just can’t hold a candle to the stuff which Cronenberg can come up with. [Credit to Rick Baker and his FX team for being up to the challenges of converting these ideas into cinematic reality] Horror is often derided as a shallow genre, one that works only on the most basic level, simply prodding the viewer’s primal fears. But Videodrome shows that this doesn’t have to be the case, and that horror can also pose questions – here, concerning the very nature of humanity. Our original analysis picked apart some of its philosophy, but didn’t talk much about its qualities as a film. And that’s a shame, since what you have here is a perfect combination of horror – one that attacks both the brain and the gut, targetting each with relentless, memorable ferocity.

[07] Max Renn (Woods) runs a seedy TV station, Channel 83, and is on the lookout for some new shows. When his pet technofreak gives him some pirate tapes of a satellite transmission, he senses something new, even though the show, called Videodrome, is nothing more than torture and sadism. On a talk show he meets media guru, Brian O’Blivion and radio DJ Nicki Brand (Harry). He shows her the tape and she shows him some interesting tricks with a cigarette end, a needle and an ice-cube (not in the original video version – in an act of rank cowardice, CIC Video cut the film themselves ‘just in case’ it might be seized, and removed several ‘offensive’ sections. The sell-through version recently released is a hell of a lot better).

Max begins to suffer increasingly bizarre hallucinations – his TV becomes a living creature, corpses appear in his bed and his stomach develops a video-cassette shaped slot, in which he ‘loses’ a gun. He turns for help to Professor O’Blivion, only to find O’Blivion is dead – he exists only as a vast collection of video tapes, looked after by his daughter, Bianca (Smits). Meanwhile, Nikki has vanished, in search of the makers of Videodrome – that she’s found them becomes clear when Max gets a tape showing her torture. Matters come to a head and Max discovers he’s been the guinea pig in a bizarre mind control experiment. The tapes were not satellite broadcasts but were planted on him by his engineer – they contain a subliminal signal which causes the visions. He is ‘programmed’ to kill his colleagues at Channel 83, but after he has done this, Bianca helps him control the hallucinations and he destroys the people responsible before committing suicide.

Apologies for this lengthy synopsis, but no shorter one would make sense; you can’t envisage anyone presenting a 25-word pitch on it to a coked-up studio executive. The film is astonishingly non-Hollywood – how many other films end with the hero blowing his brains out? But what is it all ABOUT? Let’s take a few choice quotes, and see how much of my English O-grade teaching I can remember…

“[Videodrome] has a philosophy, and that’s what makes it dangerous.”

The most obvious theme is the impact of television and other such media on the audience – I think Max Renn is meant to represent Cronenberg, a comparison made explicit during one scene in an opticians when James Woods tries on a pair of Cronenberg-style glasses. The message is, it’s not what you show that’s important, it’s the underlying meaning which counts, as against Channel 83’s policy of showing anything likely to get an audience.

“We’re entering savage new times, and we’re going to have to be pure and direct and strong if we’re going to survive them.”

Cronenberg is worried about what happens when someone becomes unable to tell the difference between reality and fantasy – the hallucination sequences are played totally straight, with no clear border to give the audience something to hold on to. It’s especially worrying when ‘reality’ is being controlled by someone else – in this case, a multinational conglomerate, of uncertain right-wing mores, who discover the power of Videodrome while experimenting with night sights for soldiers (a fact not really made clear in the final cut of the film).

“To become the New Flesh, you first have to kill the old flesh.”

One of the many interesting side avenues to this video-eye view of the world is Bianca O’Blivion and the Cathode Ray Mission she runs. This is a pseudo-religious sect which gives down-and-outs the chance to watch TV; it helps “patch them back into the world’s mixing board”. The religious angle can be extended further – “I am my father’s screen”, says Bianca at one point and the relationship between her, the Professor (who exists only on tape) and Max Renn is almost a holy trinity of Virgin, Holy Spirit & Christ, with Christ/Renn dying yet expecting to rise again as the New Flesh.

“Television is reality, and reality is much less than television.”

Very little of our world view is based on personal experience. Beyond our immediate area, we rely on television, and have to take on faith that what it’s showing us is actually happening. Simultaneously, all we see on TV are edited highlights, which means that most of our lives are less funny, exciting, scary, fast-moving, sexy and entertaining than an average evening on the network.

The entire movie is deep. And that perhaps it why it’s appeal has taken so long to filter through. On one viewing, it’s difficult to take everything in; given enough effort, however, it’s one of the finest, most genuinely thought-provoking films of all time.