They say you can’t go back. But Danny Boyle clearly didn’t listen. At the time of the original Trainspotting in 1996, he had just the one feature film under his belt, Shallow Grave. But over the two decades that followed, Boyle’s profile grew, peaking with Slumdog Millionaire, which won eight Academy Awards, including Best Director. Though in terms of pure commercial success, Boyle’s biggest achievement may be in front of him, it having been announced earlier this year that he’ll be directing the 25th installment in the James Bond franchise.

Given all this, T2 is Boyle returning to his roots, though it’s a project he had wanted to make since not long after Slumdog. There were some hurdles to overcome – not least a falling out with star Ewan McGregor, after Boyle went with Leonardo DiCaprio instead of McGregor as the star of The Beach. It took almost a decade for fences to be fully mended, and Irvine Welsh, writer of the books on which both films are based, suggested that wasn’t the only such issue adding, “There are others in the cast who’ve had a rocky road, but now also reconciled.”

While there are certainly other films with bigger gaps between sequels – Return of the Killer Shrews showed up 54 years after the original – there haven’t been many made more than two decades later, while retaining the same director, writer and leading cast. But does it work? To find out, we watched both Trainspotting and T2 Trainspotting, back to back. Here are our verdicts.

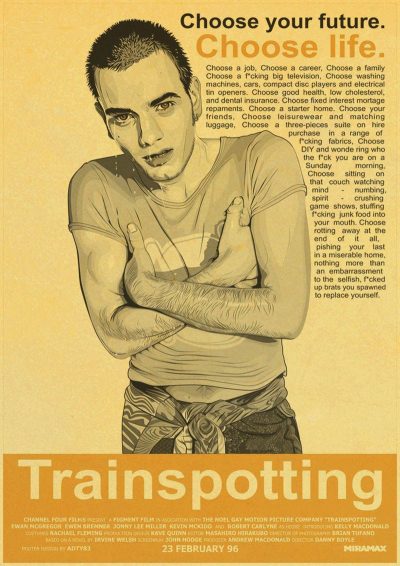

Trainspotting (1996)

Rating: B+

Dir: Danny Boyle

Star: Ewan McGregor, Ewen Bremner, Jonny Lee Miller, Robert Carlyle

The problem with most movies about drugs is they fall into one of two categories:

a) Aren’t drugs great?

b) Aren’t drugs terrible?

I’m not sure which is worse. The latter is easy to mock, as things like Reefer Madness show, but I’d argue that the former – exemplified by The Trip, one of the few films to have bored me so much, I walked out – is little better. For as with most things, the truth lies in the middle. There’s no arguing about the potential downside of drugs: particularly hard drugs (although worth noting, I’ve never met anyone who was a better person on weed). But it’d take a fool to deny their appeal, providing an escape route into a world that, for many people, is a damn sight better than the real one.

Trainspotting gets it right. There are parts which are almost an infomercial for the joys of heroin: “Take the best orgasm you’ve ever had, multiply it by a thousand… and you’re still nowhere near it.” But the destructive impact drugs can have is absolutely not glossed over in any way. Renton (McGregor) is haunted by visions of the friend’s baby who died while his parents were off their heads on smack. And then there’s the Worst Toilet in Scotland scene, in which he goes bobbing for opium suppositories. As an anti-drug message, it’s a bit more effective than “Just Say No,” put it that way.

Trainspotting gets it right. There are parts which are almost an infomercial for the joys of heroin: “Take the best orgasm you’ve ever had, multiply it by a thousand… and you’re still nowhere near it.” But the destructive impact drugs can have is absolutely not glossed over in any way. Renton (McGregor) is haunted by visions of the friend’s baby who died while his parents were off their heads on smack. And then there’s the Worst Toilet in Scotland scene, in which he goes bobbing for opium suppositories. As an anti-drug message, it’s a bit more effective than “Just Say No,” put it that way.

The other strength is characters who mostly seem like real people, to a startling degree, not often seen in movies. They’re not intrinsically “good” or “bad”, they instead have a depth which comes only from possessing aspects of both. Sick Boy (Miller) is a charming rogue, who can expound at length on the merits of Sean Connery. Spud (Bremner) is a bit dim, yet loyal to a fault. And there’s Begbie (Carlyle). A psychopath and proud of it, he instigates violence then demands retribution: or as he puts it, “That lassie got glassed, and no cunt leaves here till we find out what cunt did it.” He is perhaps the scariest Scotsman ever depicted on film, yet is the only one who doesn’t do hard drugs.

Writer John Hodge does a masterful job of taking a book written from multiple points of view and hammering it into a coherent whole, albeit one where narrative is very much secondary. The only real “plot” arc shows up late, when the four lead characters stumble into the chance of a big drug deal, and temporarily join Renton in London to execute it. The rest of the film is largely a series of loosely connected incidents: a trip to the country; Renton hooking up with a girl (Kelly McDonald) who turns out to be under age, or trying to kick his heroin habit. It’s all very episodic, yet between the performances and the energetic direction from Boyle, thoroughly engrossing.

A huge element of this is the soundtrack. Boyle has an incredible ear for picking songs that don’t just fit, they actively enhance the atmosphere. Though watching the film with closed captions (being for the benefit of Chris, given some of those Scottish accents!) lent a surreal air to it, since they also included the song lyrics. I feel I was probably better off not knowing that Lust For Life included lines such as “That’s like hypnotizing chickens.” UWOTM8? Normally, there’d be a risk such a reliance on pop music could lead to the film dating badly. This does not appear to be the case here: while the songs do locate the film in its specific era, they’ve aged very well, further testament to Boyle’s wise choices.

What probably surprised me most, twenty years on, is how funny the film is. Sure, it’s a bleak, black comedy born from a very dark place, but there are significant chunks that still made me laugh out loud. Spud’s speed-fuelled job interview, or Renton’s rant about how, “It’s shite being Scottish.” It’s a testament to how well put together the movie is, it can range from this to the terrible death of an addict – though even this has a morbid humour in its cause – without ever seeming forced or trite.

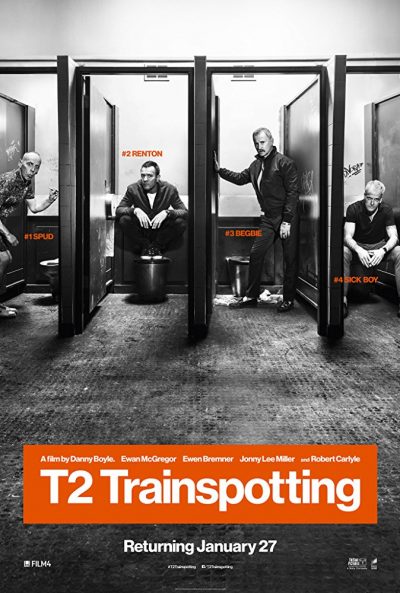

T2 Trainspotting (2017)

Rating: B

Dir: Danny Boyle

Star: Ewan McGregor, Ewen Bremner, Jonny Lee Miller, Robert Carlyle

I was a little nervous about watching this. I mean, more than two decades had passed since the first movie blazed across the screen in a tornado of drugs, music and pithy snark. A lot of things have changed since. The world has changed. Society has changed. Hell, I have changed. Would Renton (McGregor), Sick Boy (Miller), Spud (Miller) and Begbie (Carlyle) have changed? Of necessity, they must have. Yet the original film’s success was almost entirely reliant on the balance between them, something fragile which could easily be destroyed, particularly by reckless change for change’s sake.

You can breathe easy. Time has not dulled the edges of these characters. Older? Certainly. Wiser? Not so much. Three-quarters of them have at least somewhat matured, the exception being Begbie who, inevitably, is still the same violent psychopath we knew and loved. But even he, we discover, has a wife and son – the latter, much to his father’s horror, is going to college to study… [the shame!] hotel management. It’s really only a sidelight, but gives you some indication of the approach this takes: the more things change, the more they stay the same. For Sick Boy is still a scammer and Spud a gentle idiot.

You can breathe easy. Time has not dulled the edges of these characters. Older? Certainly. Wiser? Not so much. Three-quarters of them have at least somewhat matured, the exception being Begbie who, inevitably, is still the same violent psychopath we knew and loved. But even he, we discover, has a wife and son – the latter, much to his father’s horror, is going to college to study… [the shame!] hotel management. It’s really only a sidelight, but gives you some indication of the approach this takes: the more things change, the more they stay the same. For Sick Boy is still a scammer and Spud a gentle idiot.

It’s Renton who kick-starts things. He has been living in Amsterdam after absconding with most of the drug-deal proceeds in the original film. A heart-attack gives him a new “lust for life”, as it were, and he returns to Edinburgh to make peace with his pals. He’s no longer a heroin addict, but his marriage has failed and he’s at a dead-end. He links up with Sick Boy, now running blackmail scams with his Bulgarian girlfriend, and they join forces on a scheme to open a brothel and make a bogus application for an EU development grant – though Renton doesn’t realize that Sick Boy still holds a grudge about his friend’s earlier betrayal.

Boyle does a good job of treading the difficult line between having respect for the original, without toppling over into reverence. It doesn’t have quite the same sense of not giving a flying fuck, but that’s a reasonable enough reflection of the way time marches on. The characters all have the weight of responsibility, and that tends to act as an an anchor. However, Renton’s new-found freedom from work and marriage still allows him to drag Sick Boy into trouble. Most notable is a theft from a Protestant social club which ends up involving an impromptu vocal performance, reminiscent of Borat’s Throw the Jew Down the Well from The Ali G Show. It’s epic, hilarious tastelessness – “…there were no more Catholics left.” [Very catchy, too. Is it available as a ring-tone?] And the scene makes the core point of the film: you can’t live in the past forever.

Compared to the original, there is additional plot here, which is not necessarily a good thing, and I’d like to have seen more of Kelly McDonald – she shows up for a quick cameo as a lawyer. Probably inevitably, it falls a little short when trying to recapture the intensity of its younger, rawer self; then again, don’t we all? It’s at its best when not trying, accepting the fact that what’s past is past, and looking forward to a future that remains as uncertain and doubtful as it ever did. “Choose updating your profile, tell the world what you had for breakfast and hope that someone, somewhere cares.” The more things change, indeed.