Luc Besson was one of, if not, the preeminent French director of the nineties, creating films that offered a rare combination of art and commercialism. Late in the previous decade Besson was classified as part of the “Cinéma du look” movement, along with fellow directors Jean-Jacques Beineix and Leos Carax. But while their careers then sputtered and stalled out as we approached the turn of the millennium, Besson’s blossomed, beginning with Nikita. It became one of the top 10 foreign-language films at the American box-office to that point, subsequently spawning two TV incarnations and a Hollywood remake, as one of the cornerstones of the “girls with guns” genre. After making the documentary Atlantis, Besson moved into English-language films – though rather than moving to America, still operated out of France, shooting much of both Léon: The Professional and The Fifth Element there.

After his last film of the decade, The Messenger: The Story of Joan of Arc, was less successful, Besson switched more into production. His film company EuropaCorp was responsible for several successful franchises, including The Transporter and Taken, though his directorial contributions came mostly in an unexpected fashion: the children’s film and animation/live-action hybrid, Arthur and the Invisibles, plus its sequels. Like much of EuropaCorp’s output, it was more successful commercially than critically, a tendency sustained with Besson’s return to big-budget action in 2014, Lucy, which grossed more than ten times its budget, despite rather lukewarm reviews. Emboldened by its success, Europacorp and Besson went all in this summer, on their biggest feature ever, Valerian and the City of a Thousand Planets.

They might be regretting it.

For the film, which cost almost $210 million (admittedly before tax credits), barely brought in that much in worldwide box-office. Fortunately, creative financing and pre-sales mean that whatever losses occur will largely be escaped by EuropaCorp, whose exposure is reportedly limited to less than $20 million. So while Besson’s dreams of a franchise in the Valerian universe are likely dead in the water, the film’s severely disappointing returns will not likely lead to EuropaCorp going down the road, say, of Carolco, into bankruptcy.

That would have been a shame, since over the last quarter century, Besson has been one of a kind. Few film-makers can match his breadth, going effortlessly from directing art-house fantasy like Angel-A to writing and producing kung-fu flicks starring Jet Li (Kiss of the Dragon and Unleashed). He’s the kind of talent we need more of, and even his less successful creations are usually worth a look. Having recently seen Valerian, I had an urge to dig into Besson’s back catalogue and we ended up re-watching what are arguably his two other most well-known movies as a director. Have they stood the test of time?

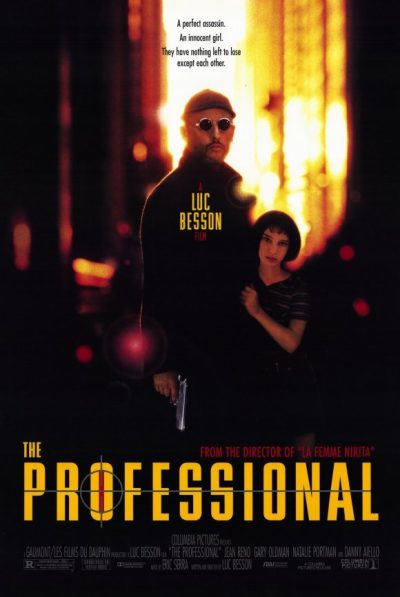

Léon: The Professional (1994)

Rating: A

Dir: Luc Besson

Star: Jean Reno, Natalie Portman, Gary Oldman, Danny Aiello

This may be the greatest opening to a film ever, as Léon (Reno) accepts a mission from his Mafia mentor, Tony (Aiello), and carries it out. He doesn’t just slide into a hotel, kill all the henchmen and deliver a crystal-clear message that the New York presence of “Mr Jones” is unwanted. No: Leon does so, only after getting the henchman in the lobby to call up and warn the boss of his impending arrival. It demonstrates self-assurance of the highest level, and is filmed in a way so that the audience don’t clearly see him at any point. It brilliantly establishes Léon as a mythic, near-superhuman “ghost faced killer”. Then we meet Léon, and it flips the script completely.

For he’s a middle-aged man-child, who loves movies from the Golden Age of Hollywood and his pot plant in equal measure, while living alone in his apartment, drinking milk and sleeping in a chair. A less threatening creature, it’s hard to imagine – especially in contrast to the film’s antagonist, Stansfield (Oldman). For he too is initially hidden from the audience, as he and his cronies quiz Léon’s neighbour as to why the drugs they gave him, are no longer pure. When no good answer is forthcoming, we discover Stansfield is a highly dangerous animal: a volatile psychopath, with a fondness for pharmaceuticals. Yet, like Léon, there’s an odd quirk – a fondness for classical music. This helps set him apart from the usual “Bad Lieutenants”, because we eventually also discover Stansfield is not the mob boss we initially expect, but a corrupt and very rogue DEA agent.

The subsequent slaughter ends the life of not just the perp, but his wife and two of the three children. The exception is Mathilda (Portman, in her feature debut), who is reluctantly granted refuge in Léon’s apartment. She may be a truant, but has won the attendance prize at the school of hard knocks, asking him, “Is life always this hard, or is it just when you’re a kid?” Discovering his day-job (he doesn’t exactly do much to hide it), she offers to hire him to kill her family’s killers. Not that she liked most of them, mind, save her baby brother: “What the hell did he do? He was four years old.” Though he declines the job, she convinces him to take her on as an apprentice, with the eventual aim of taking revenge herself.

The subsequent slaughter ends the life of not just the perp, but his wife and two of the three children. The exception is Mathilda (Portman, in her feature debut), who is reluctantly granted refuge in Léon’s apartment. She may be a truant, but has won the attendance prize at the school of hard knocks, asking him, “Is life always this hard, or is it just when you’re a kid?” Discovering his day-job (he doesn’t exactly do much to hide it), she offers to hire him to kill her family’s killers. Not that she liked most of them, mind, save her baby brother: “What the hell did he do? He was four years old.” Though he declines the job, she convinces him to take her on as an apprentice, with the eventual aim of taking revenge herself.

After this brisk opening, the film then enters a more subdued middle section, during which time Mathilda and Léon bond. The relationship between the pair was the subject of much controversy, and largely led to the film being edited down from 133 to 110 minutes for initial release, in response to a poor reaction at test screenings in Los Angeles. If anything, it perhaps seems even more questionable now, in the post Jimmy Saville era. Admittedly, it’s very clearly specified that Léon is absolutely not interested in her, despite Mathilda virtually begging him to sleep with her. But even allowing for the European sensibilities of Besson, the sight of the 12-year-old Portman doing a Madonna impression or vamping it up as Marilyn Monroe is kinda creepy. It doesn’t help knowing that Besson was then married to Maïwenn Le Besco, whom he got pregnant when she was 15 and he more than twice her age. [Le Besco has a minor role here, playing Mr. Jones’s hotel prostitute]

However, the cuts weren’t just to tone done the relationship: a lengthy sequence which depicts them going on multiple jobs together was removed too. This is particularly important, since it sets up both the “ring trick” of the climax, plus the scene where Matilda believes herself ready for her own attempted hit on Stansfield and his crew in the DEA office. In the originally released version, the latter comes relatively out of nowhere, though in both, it’s hard to tell the time-frame. Are they hanging out for weeks? Months? It doesn’t really matter, in the end. Léon has to rescue Matilda from her ill-conceived scheme, and the film then kicks it back up for the grandstand finale.

Besson had already proven his action chops with Nikita, and hones them to an even higher level here, as Stansfield sends everyone (“What do you mean, everyone?” “EVERYONE!!!!”) into the apartment building where Léon and Matilda have been living. It’s a master-class in the art of escalation. The end of the resulting siege is almost as perfect as the opening: poignant yet triumphant, and probably the only time a movie has made me want to cheer and burst into tears simultaneously. It’s interesting to note that through all the carnage (and even in the extended version of the film), Matilda never shoots anybody with anything more than paint. Although this was not the case in the original version of the script, it seems Leon was intent on protecting her from the consequences. As he puts it, “Nothing’s the same after you’ve killed someone. Your life is changed forever.”

The three lead performances here are all near-perfect. They’re completely different in tone and approach, yet mesh beautifully to create something which feels greater than the sum of the parts. It’s probably Oldman who is the key. Both Matilda and Léon are, to varying extents, Besson revisiting characters from Nikita. But that film lacked any particular villain, beyond the faceless establishment that was intent on crushing the heroine’s spirit. The void is filled perfectly here by Stansfield, with Oldman often flying by instinct. For example, his the famous delivery of the “Everyone!” line was improvised, and when he’s interrogating Matilda’s Dad in Stansfield’s first scene, the father’s discomfort is largely genuine, because the actor playing him did not realize Oldman would be getting so close.

Slight qualms about the Matilda/Léon aside, this remains as wonderful as it was when I first saw it, as the London Film Festival’s closing night movie in 1994. It’s a great action film, yet is one with a huge amount of emotional heart, and also combines European and Hollywood styles of cinema in a way rarely attempted, and even less often successfully accomplished.

[February 2010] Besson had been building towards top-class action potential through his first four features, and finally hit the bullseye with the fifth. While set in New York, it’s a concept that could never be made in Hollywood: not so much for the mob killer being the hero, as for the 12-year old (Portman, in her feature debut) who accompanies him, after her family, who live next door to Leon (Reno), is wiped out by Oldman and his posse of corrupt DEA agents. The transgressive potential of their relationship – even if never realized – was enough to get it shorn of 25 minutes for its US release as a result.

[February 2010] Besson had been building towards top-class action potential through his first four features, and finally hit the bullseye with the fifth. While set in New York, it’s a concept that could never be made in Hollywood: not so much for the mob killer being the hero, as for the 12-year old (Portman, in her feature debut) who accompanies him, after her family, who live next door to Leon (Reno), is wiped out by Oldman and his posse of corrupt DEA agents. The transgressive potential of their relationship – even if never realized – was enough to get it shorn of 25 minutes for its US release as a result.

But looking at it now, it’s clear that Leon could never even contemplate such a possibility, and for the vast bulk of the time, it comes over more as a father-daughter movie than anything else. As such, it’s one of the most tender, completely platonic relationships ever in an action movie. All three leads are amazing. Portman delivers one of the best by an actress her age (she was only eleven when cast), while Leon’s stoicism is betrayed almost entirely by the emotions he puts over in his eyes. The latter’s stillness is a particularly-sharp contrast to Oldman, who chews the scenery to marvellous effect. I’ve realized how, in many of my favourite films, the villain is one of the most memorable aspects, and that’s true here, in spades: Oldman’s Stansfield is a complete loose-cannon, who could do anything to anyone at any time, and that’s what makes him dangerous, combined with rat-like cunning.

There isn’t an aspect of the movie that’s less than a joy, from the beautifully-fluid cinematography through to Eric Serra’s marvellous score, and the final assault, in which an every-increasing stream of SWAT men assault Leon’s apartment, is one of the most beautifully-choreographed and paced action sequences of all time. [Not least for Stansfield screaming, “Bring me everyone… EVERYONE!“] And the moments which follow it, with Leon heading out of the darkness and into the daylight, provoke tears and cheers in closer proximity than any other movie I’ve seen.

The Fifth Element (1997)

Rating: B

Dir: Luc Besson

Star: Bruce Willis, Milla Jovovich, Gary Oldman, Ian Holm

For context, this was watched the night after Valerian and the City of a Thousand Planets. Or, rather, re-watched, it having been seen any number of times over the past twenty years, not least at a 1998 open-air screening in London’s Hyde Park. It made for an interesting contrast, succeeding significantly better than Valerian, mostly because it demonstrates a key point about films with a strong sense of visual style. In order for them to work, the performances in them need to be equally strong, or they will be swept away by the sparkly distractions.

The latter is what happened in Valerian, and doesn’t here, thanks to Willis anchoring the film brilliantly – despite the significant handicap of having to wear a lurid orange vest for a good chunk, apparently chosen to match the hair of superpowered space girl Leeloo (Jovovich). His ex-soldier turned flying cab driver is down to earth and personable: the kind of guy with whom you could drink several beers. He gets drawn into the whole “saving the world” thing, after Leeloo literally drops into his cab. She turns out to be the key to defusing an onrushing extraterrestrial menace. Arrayed against them are the forces of industrialist Jean-Baptiste Emanuel Zorg (Oldman), who may be worth billions, but still apparently does his own hair. In the dark. With his left hand. Before trying to cover the results with a bit of Tupperware.

The latter is what happened in Valerian, and doesn’t here, thanks to Willis anchoring the film brilliantly – despite the significant handicap of having to wear a lurid orange vest for a good chunk, apparently chosen to match the hair of superpowered space girl Leeloo (Jovovich). His ex-soldier turned flying cab driver is down to earth and personable: the kind of guy with whom you could drink several beers. He gets drawn into the whole “saving the world” thing, after Leeloo literally drops into his cab. She turns out to be the key to defusing an onrushing extraterrestrial menace. Arrayed against them are the forces of industrialist Jean-Baptiste Emanuel Zorg (Oldman), who may be worth billions, but still apparently does his own hair. In the dark. With his left hand. Before trying to cover the results with a bit of Tupperware.

He’s working at the behest of the mysterious and largely forgotten “Mr. Shadow”, and this lack of any real villain is probably the film’s greatest weakness. Why would Zorg, or anyone, actively work toward the destruction of the entire planet? I guess it’s because he’s a movie villain, and forethought has never been their great strength. Yet Oldman’s commitment to the role of villain sufficiently echoes the same he brought to Leon, for this to work, and it becomes easy to forget that, technically, Zorg is a henchman rather than the Big Bad himself.

The rest meshes impressively, creating a credibly messy world that seems no less credible twenty years later, and the movie overall has aged well. There are occasions when the self-indulgence pokes through, such as the opera song (played by Besson’s then-wife, Maïwenn Le Besco – he left her during production for Jovovich, which must have been awkward). However, they’re so cool and memorable, you get why Besson left them in, and forgive him – though you can sometimes tell he started writing the script when he was 16. I must confess to absolutely hating Chris Tucker’s obnoxious DJ character, Ruby Rhod, at the time: I’ve defrosted somewhat since, perhaps because it appears he’s in it less than I remember.

The result is a rare beast these days: big-budget, spectacle-driven SF, that’s wholly original in its source, rather than being adapted from an existing entity. Besson went his own way, with a vision in his head and the motivation to put it on screen. While the results aren’t universally successful, he can only be applauded for the effort.

[October 2009] It’s been more than eleven years, two months since I last saw this – I know with certainty, because it provided one of my most memorable cinematic experiences (linked above). However, that said…it isn’t actually a very good movie. Besson wrote the original screenplay when he was still in high school, and it feels like it went straight from a 15-year old’s jotter to the screen. The script is a complete self-indulgent mess, throwing just about everything you can imagine into the mix, stirring it up and throwing it at the screen. Taxi driver Korben Dallas (Willis) has a young woman fall into the back of his cab, and discovers that she is the key to humanity’s survival from the ‘Great Evil’, which apparently shows up every 5,000 years to exterminate all life on Earth. Which, by my reckoning means it’s been repelled more than twelve thousand times since the dinosaurs went extinct. Got to admire such persistence, if nothing else. Meanwhile, Zorg (Oldman) is out to stop her – apparently, not quite clear that the “exterminate all life” concept would include him.

Like I said: not well thought-out, in a very similar way to Babylon AD – whose director, oddly enough, plays the mugger who tries to attack Willis in his apartment – and with a similar devotion to style over substance. However, where Fifth is vastly superior, is in the performances, which rescue what has the potential to be a disaster and turn it into something watchable. All the cast are at least adequate in their roles: yes, Chris Tucker is still astonishingly irritating, yet I now sense that was at least partly the point [I just don’t think Besson realized quite how much]. Willis and Jovovich have exactly the right world-weary and other-worldly approaches respectively, whole Oldman overcomes what has to be one of the crappest haircuts in cinematic history, chewing the scenery to good effect. It’s movie eye-candy of the highest order, and on that basis can’t be condemned out of hand – the budget is all up on the screen, and it still looks marvellous, even more than a decade after its release. However, when measured by Besson’s high standards, it’s definitely no Leon. B-

Valerian and the City of a Thousand Planets (2017)

Rating: C

Dir: Luc Besson

Star: Dane DeHaan, Cara Delevingne, Clive Owen, Ethan Hawke

For the most expensive European, and most expensive independent film ever made, this is surprisingly forgettable. Coming in at a budget of 200 million Euros [whatever that works out to in real money], you can’t necessarily argue the money isn’t up there on the screen. But visual spectacle is the cinematic equivalent of gorging yourself on Halloween candy: you’re soon filled with emptiness and regret. I watched Valerian less than 36 hours ago, and already am struggling to remember many scenes. I guess the bit where Rihanna was a shape-shifting pole-dancer was kinda cool?

Yet it may be significant that this sequence could be excised completely, without harming the film in the slightest. The main problem is likely the central performance, where DeHaan’s Valerian is as blandly annoying as a carton of soy milk, coming over like a young Leonardo DiCaprio. And when I say young, the 31-year-old DeHaan looks about 12, certainly not old enough to be the major in the space police he’s supposed to be. There were times when I would have wagered he and sidekick Sergeant Laureline (Delevigne) were actually part of a Spy Kids reboot, and was anticipating the arrival of Danny Trejo. So when they start with the sexy Euro-banter, it’s all a bit creepy.

Yet it may be significant that this sequence could be excised completely, without harming the film in the slightest. The main problem is likely the central performance, where DeHaan’s Valerian is as blandly annoying as a carton of soy milk, coming over like a young Leonardo DiCaprio. And when I say young, the 31-year-old DeHaan looks about 12, certainly not old enough to be the major in the space police he’s supposed to be. There were times when I would have wagered he and sidekick Sergeant Laureline (Delevigne) were actually part of a Spy Kids reboot, and was anticipating the arrival of Danny Trejo. So when they start with the sexy Euro-banter, it’s all a bit creepy.

The film is set six centuries into the future, when the International Space Station has grown so large it has been pushed out of Earth orbit and has become an independent entity, an interchange for data and commerce between all forms of alien life. Beyond that, the plot is disappointingly generic, definitely over-stretched, and appears largely cribbed from Avatar [a film which Besson admits was a significant inspiration]. There’s a pacifist alien race, to which Valerian has a psychic connection, who are under threat from the evil humans and their military forces, led by Arün Filitt (Owen). At least Besson is not as stridently hectoring in tone as James Cameron.

The main appeal is the visual side, as you’d expect, with a range of impressive set-pieces, beginning with the Big Market, a bazaar which exists outside of our dimension and is part tourist attraction, part Silk Road, and all spectacle. Alpha, as the ISS is now known, is a similarly sprawling environment where you can strongly sense the influence of the original bande dessinée which inspired this – and, just as in most films based on comic books, it is significantly stronger on the look than the nutritional content. We’re back to the Halloween candy comparison.

Save for his Arthur kids’ series, Besson took almost the entire 2000’s off directing, and seems to have lost the knack: none of his output since has come close to matching the work delivered in the nineties. It’s clear Besson is a big fan of the comics, and that may be part of the problem. Someone less enamored of the source might have been more willing to adopt a more critical approach and address the almost inevitable weaknesses, such as the complete lack of any reason to care about Valerian. When Rutger Hauer shows up for 30 seconds as President of the World State Federation, it’s a criminal waste of talent. I’m left feeling kinda the same way about Besson.