The history of low-budget horror is littered with knock-offs, cash-ins and mockbusters. Whatever works at the box-office, video-store or on a streaming service, will inevitably result in a flood of imitators, seeking to capture their share of the market. The morality of these is on a sliding scale. At the more honest end, you have those which are more inspired by the successes than merely seeking to copy them. After The Blair Witch Project took in almost a quarter of a billion worldwide, any idiot with a camcorder decided they could also make a found footage feature. And it feels like most of them did.

More questionable are those which seek to muddy the waters by confusing the viewer, through similarities in title, plot or artwork. The masters here are, of course, The Asylum. They’ve been doing this sort of thing since 2005, when their version of War of the Worlds came out one day before the Spielberg feature his movie screens. It’s particularly relevant here, because the source material, H.G. Wells’s classic novel of alien invasion defeated by microbes, was written in the nineteenth century, and so comfortably in the public domain. It also helped The Asylum that film titles cannot typically be trademarked under US law.

Copyright terms have gradually been getting extended. The first American copyright act, in 1790, allowed for a period of fourteen years, with a possible extension of the same length. The infamous Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act of 1998, extended it to the life of the creator plus seventy years. It’s widely believed to have been passed at the behest of Disney, whose original creations were creeping towards the public domain. The extension meant additional coverage for them, but only delayed the inevitable. The door cracked open on January 1st, 2022, when the original Winnie-the-Pooh stories by A.A. Milne came out of copyright, and anyone could then adapt them.

Note, however, that limitations still applied. Only the version of Winnie present in the books is available: any changes or additions made for the Disney versions were unable to be used. For example, in the latter, the bear with very little brain is called Winnie the Pooh, no hyphens. Any adaptation needs to include the dashes present in A.A. Milne’s work, whenever the character’s name is written, such as in the title. Tigger was also not initially accessible, because he did not appear until 1928, and so didn’t become public domain until two years further down the road, in January 2024. That’s why he was not in the first Blood and Honey film, but appeared in the sequel.

The massive success of Winnie-the-Pooh: Blood and Honey has a lot to answer for. It was shot in just ten days, on a budget of about $100,000 by microbudget British horror company Jagged Edge Productions. But despite that, and critical savaging – sitting at 3% fresh on RottenTomatoes – the movies still took in 77 times its cost at the box-office, plus who knows how much more in ancillary sales, on DVD and streaming. Just as with Blair Witch, its commercial success opened the door to every low-rent film-maker wanting to trawl the public domain waters, in search of newly accessible material, which could potentially be turned into cinematic gold silver empty soda cans.

In particular, Jagged Edge haven’t hung around, announcing the Twisted Childhood Universe – probably better known as the Poohniverse. In addition to the two Pooh movies, this includes Peter Pan’s Neverland Nightmare, plus upcoming movies offering horror takes on Bambi, Pinocchio and Mary Poppins. Though they didn’t prove as successful – Neverland took only $230K – the low costs make it easy for them still to turn a profit. The year after Winnie’s entrance, The Hardy Boys and Lovecraft’s The Color out of Space entered the public domain, but it was January 1st, 2024 that was marked on a lot of calendars. Because that’s the day the first Mickey Mouse short, Steamboat Willie, lost its copyright protection.

There is arguably no more iconic figure. While the Steamboat version is different in a number of ways from the current one, purely in name recognition alone, this has a huge amount of value. The problem is, so far it seems the opportunities presented, rather than being used in imaginative ways, have been simply, “Let’s make X a serial killer.” Which is… okay, but of very limited long-term appeal. [I want a Mickey-in-prison movie, hopefully titled Mouseschwitz] Admittedly, I certainly appreciate the irony of Disney – a company which shamelessly strip-mined public domain fairy-tales for decades – now finding the river flowing in the other direction. It’s not going to stop either.

For this January, the characters of Tintin and Popeye became fair game, and in two years, the classic Universal monster movies of Dracula and Frankenstein will join them. But you probably want to look forward to the mid-thirties, when we should get access to the likes of The Hobbit (2033), the film version of The Wizard of Oz (2035 – bring on those ruby slippers!), Batman (2035), and Wonder Woman (2037 – also Captain America and Aquaman). For now though, while we await the April arrival of the highest-profile Mickey adaptation, Screamboat, starring David Howard Thornton (a.k.a. Art the Clown from the Terrifier franchise), let’s look at three entries which sought to take Steamboat Willie in a darker direction.

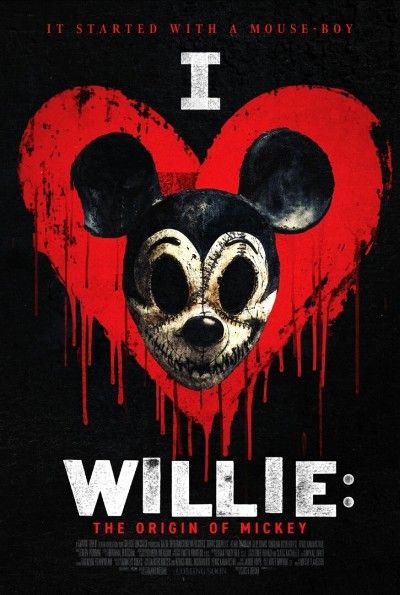

I Heart Willie (2024)

Rating: C+

Dir: Alejandro G. Alegre

Star: Maya Luna, Micho Camacho, David Vaughn, Daniela Porras

The first half of this seems to fall victim to the same problems which are endemic to the genre. There is some potential in an opening, which talks about a half-mouse, half-boy hybrid, Willie fleeing Germany for the United States. There, he seeks sanctuary from bullying and abuse in a remote, decrepit mansion. Where, naturally, he (Vaughn) captures, tortures and skins people, while wearing a Mickey Mouse Steamboat Willie mask. Hey, if not exactly Dostoevsky, there’s a bit of effort. Quite why Willie chooses to wander round with his shirt off so much is less clear, but he does have a nice set of abs, and it would be a shame to cover them up.

With that foundation in place, the film then sits back, as if its work here is done. We meet YouTubers Daniel (Sergio Rogalto) and Nico (Camacho), who figure the urban legends surrounding Willie’s hideaway would make perfect fodder for their channel. Along with them are their more-or-less girlfriends, Nora (Luna) and Jess (Porras), and the film largely grinds to a halt for a solid half-hour as we “get to know” these young people. Quotes used, because I will not be smashing the like or subscribe buttons. I’m presuming the cast are largely Mexican – the movie was made in Michoacan – but speak English, so we’re likely deep in “acting in a second language” territory, and this makes for a bumpy journey.

Things improve somewhat once Willie gets his hands on a couple of them, after they make the inevitably fatal decision to try and have sex. In an abandoned, blood-stained truck. Bit of a warning sign, I would have said. But I am no longer a horny young person, turned on by murder vans. Of course, this being 2025, even slashers are no longer as exploitative of young women as they were, and a quick flash of boob is all we get. The gore only impresses intermittently too. While Willie is enthusiastic about flaying the flesh off his victims (top), the removal of one’s leg at the knee is disappointingly off-screen, and it felt like this was going to peter out into a weak slasher, Disney or not.

Things improve somewhat once Willie gets his hands on a couple of them, after they make the inevitably fatal decision to try and have sex. In an abandoned, blood-stained truck. Bit of a warning sign, I would have said. But I am no longer a horny young person, turned on by murder vans. Of course, this being 2025, even slashers are no longer as exploitative of young women as they were, and a quick flash of boob is all we get. The gore only impresses intermittently too. While Willie is enthusiastic about flaying the flesh off his victims (top), the removal of one’s leg at the knee is disappointingly off-screen, and it felt like this was going to peter out into a weak slasher, Disney or not.

However, the final third is laudably fucked-up, and if the final result isn’t a classic, it’s considerably better than this was looking. The uptick is entirely at the door of Nora, who… turns out to be a very strange little girl indeed. We get some hints about this from her ex-boyfriend when he’s talking to Jess about their sex life: this only scratches the surface. I’ll say no more, except to note that it’s a creepy twist on the already potentially questionable ‘Disney adult’ fandom. I feel like going down this road from the start would have been an improvement, offering a satirical twist on the otherwise all-too common slasher approach. If they do I Heart Willie 2 – preferably guerilla filmed at Disneyland – I’m down for that.

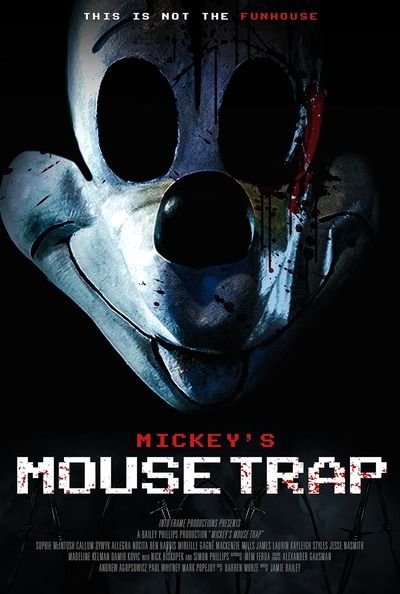

The Mouse Trap (2024)

Rating: D

Dir: Jamie Bailey

Star: Sophie McIntosh, Mackenzie Mills, Callum Sywyk, Simon Phillips

This was the first film to take advantage of Mickey’s new public domain status, being announced on January 1, the day the Disney copyright lapsed. The movie was already in the can, at that point called Mickey’s Mouse Trap (as the poster below shows), having been shot in Ottawa over eight days the previous September. In the wake of the announcement, a theatrical release was discussed, but it ended up seeping out, direct to streaming, in August. This makes sense, because it’s a bit shit. There is almost no effort put into this, beyond giving the killer a Mickey Mouse mask as he stalks vacuous young people round an amusement arcade, late at night. Might as well have been a Ronald Reagan mask, it’s that unimportant.

Beyond this, significant parts don’t make sense. The killer can literally teleport, which as you all know [/s], is a key component in the narrative of Steamboat Willie. He’s afraid of strobing flashlights, because… Nope. I got nothing, any more than why said torches are part of the staff equipment in an arcade. But most glaringly of all, the story is recounted in flashback by Goth Rebecca (Mills), to a page of sceptical police officers. She’s explicitly referred to as the sole survivor. Except, when the credits roll, there are still at least two others alive. Little wonder one cop says during her explanation, “Wait, is this some terrible subplot of a ’90s slasher film? It sure sounds like a really bad ’90s film.” Self-awareness. Missed it by that much.

It begins semi-promisingly, with a lengthy disclaimer crawl which approaches Holy Grail levels of surreal textual openings. But thereafter, it’s played depressingly straight, without much desire to play with the concept. It’s vaguely suggested the killer might be the arcade owner, who seems to be a collector, and has been possessed by the spirit of the mask somehow. This is never addressed, and doesn’t explain any of the other elements. A general lack of good gore and gratuitous nudity doesn’t help, with only the occasional bit of acidic dialogue provoking an appreciative snort. Not-so final girl Alex (McIntosh), the sensible employee, is somewhat likeable, trying to keep her head, when all about are losing theirs. Until she can’t.

It begins semi-promisingly, with a lengthy disclaimer crawl which approaches Holy Grail levels of surreal textual openings. But thereafter, it’s played depressingly straight, without much desire to play with the concept. It’s vaguely suggested the killer might be the arcade owner, who seems to be a collector, and has been possessed by the spirit of the mask somehow. This is never addressed, and doesn’t explain any of the other elements. A general lack of good gore and gratuitous nudity doesn’t help, with only the occasional bit of acidic dialogue provoking an appreciative snort. Not-so final girl Alex (McIntosh), the sensible employee, is somewhat likeable, trying to keep her head, when all about are losing theirs. Until she can’t.

I guess it could be seen as laudable that the makers don’t lean on the crutch of obvious satire. The problem is, what you have otherwise is, at best, a thoroughly generic slasher – with a pair of rodent ears strapped onto it. It doesn’t turn this into good cinema, any more than attaching those ears to our cat, would turn him into Mickey Mouse. The movie manages a near-Herculean feat, of making me feel sympathetic towards Disney, and that’s not something I have experienced this side of the Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act. In the end though, I do not dislike this because it tarnishes the reputation of a beloved childhood icon. I dislike this, because it largely sucks.

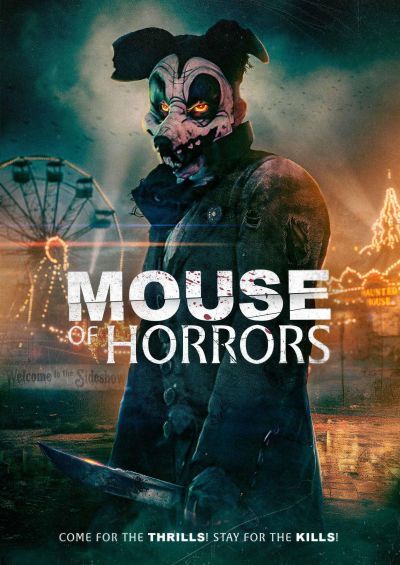

Mouse of Horrors (2025)

Rating: C

Dir: Brendan Petrizzo

Star: Natasha Tosini, Chris Lines, Lewis Santer, Stephen Staley

Few places are sadder than a British seaside resort out of season. Though it’s more a mournful sense of loss and vague emptiness, than a “you’re going to get stabbed repeatedly by a hideous monster with the head of a deformed rodent” kind of way. Guess which direction this takes? Mad scientist and former high-security prisoner Dr. Rupert Mouse (Lines), has set up his lab with a sea-view, and the aim of continuing his unsanctioned experiments. These have already created the creature previously mentioned (Santer), as well as “Bear” (Staley), who might perhaps resemble another beloved character, recently to enter the public domain. Next up? A bride for them, constructed from parts hacked off tourists and locals.

Meanwhile, Chloe (Tosini) is preparing to head off to California, and a farewell party of sorts has been organized overnight at the fairground. Absolutely no prizes for guessing how that goes: as well as such nocturnal excursions usually do. The bulk of this is straightforward stalk and slash. The two monstrous siblings – the rodent in particular, though the makers seem curiously unwilling to name names – chases Chloe and her pals about, knocking them off, one by one. Because “leaving” or “calling the police” doesn’t seem like it’s an option that occurs to any of them. In its location, this is not dissimilar to The Mouse Trap‘s arcade, though at least that had doors which the killers could lock.

An absence of logic aside – and we are talking about a slasher movie here, so it goes with the territory – this isn’t awful. The dysfunctional family of Dr. Mouse and his two “sons” is a nice twist, even though he looks more like a vagrant biker than a physician. A white coat was apparently too much to ask. It’s a shame the “Bride” is only marginally glimpsed at the end: do film-makers know that Minnie Mouse is in the public domain too? Despite the British location – the fairground is Knightly’s, located in North Wales – Petrizzo and a few other people involved here, are Asylum refugees. So they know their way around low-budget horror; was amused to see Anthony C. Ferrante’s band, Quint, providing most of the music.

An absence of logic aside – and we are talking about a slasher movie here, so it goes with the territory – this isn’t awful. The dysfunctional family of Dr. Mouse and his two “sons” is a nice twist, even though he looks more like a vagrant biker than a physician. A white coat was apparently too much to ask. It’s a shame the “Bride” is only marginally glimpsed at the end: do film-makers know that Minnie Mouse is in the public domain too? Despite the British location – the fairground is Knightly’s, located in North Wales – Petrizzo and a few other people involved here, are Asylum refugees. So they know their way around low-budget horror; was amused to see Anthony C. Ferrante’s band, Quint, providing most of the music.

Their experience helps deliver the necessary energy, which goes some way to countering the industrial-strength stupidity of the plot and characters. Santer puts a bit of effort into giving his mouse some touches of character too. Eventually, dissension in the ranks, largely fostered by he and Bear’s ‘father’, pits the two monsters against each other, in a fight whose conclusion I still didn’t understand, after multiple viewings. Oh, well. I was just about adequately amused, and that’s what matters. It feels like this is intended as the start of another horror ‘universe’; Chloe’s dad is writing a book called Mouseboat Massacre, and that’s the title of an upcoming film, in which Tosini stars. I’m not sure if that should be regarded as a promise or a threat.