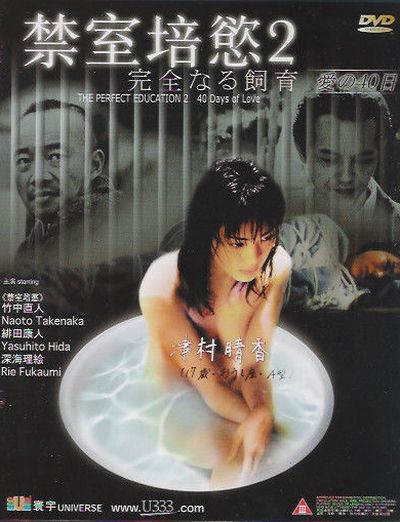

Rating: C+

Dir: Yoichi Nishiyama

Star: Rie Fukami, Yasuhito Hida, Naoto Takenaka

Full disclosure: I have not yet seen the first film in this series. This DVD was acquired at least a decade ago, as part of a batch, but has sat on the unwatched shelf ever since. I think the salacious sleeve proved more a deterrent than an inducement. It is actually rather misleading with its implication, on a casual glance, of a woman kept in a cage. In reality, it was surprisingly thoughtful, as much psychological drama as S/M porn. It depicts a case of Stockholm syndrome (or Helsinki syndrome, if you’re a Die Hard fan), with what might be a rather disturbing agenda. Sometimes, it’s okay to kidnap women! It can help them and help you! Hmm. About that…

Takenaka was the star of the original movie and, in what might be a sardonic joke, the sequel sees him playing a therapist, treating its protagonist, Haruka (Fukami), whom he sees every day on the bridge outside his office. She initially claims to be looking for UFOs (!), but this turns out to be cover for a set of largely repressed memories involving her abduction as a teenager by teacher Sumikawa (Hida). He keeps her almost entirely confined to his apartment for the period of the title, and the pair develop a strange relationship. Haruka initially tries to escape, until Sumikawa gives her a pair of scissors to cut the tag off a dress. Her decision not to stab him marks a turning point, and trust, albeit of the Patty Hearst flavoured variety, is gradually established on both sides.

Takenaka was the star of the original movie and, in what might be a sardonic joke, the sequel sees him playing a therapist, treating its protagonist, Haruka (Fukami), whom he sees every day on the bridge outside his office. She initially claims to be looking for UFOs (!), but this turns out to be cover for a set of largely repressed memories involving her abduction as a teenager by teacher Sumikawa (Hida). He keeps her almost entirely confined to his apartment for the period of the title, and the pair develop a strange relationship. Haruka initially tries to escape, until Sumikawa gives her a pair of scissors to cut the tag off a dress. Her decision not to stab him marks a turning point, and trust, albeit of the Patty Hearst flavoured variety, is gradually established on both sides.

It’s creepy in a whole number of ways, not least Sumikawa’s insistence on his captive calling him “Papa,” and the daily ritual of weighing Haruka and taking a Polaroid. These go up on the wall, seven in a row, and act as the film’s calendar. The permanent impact on the victim isn’t to be denied either: when she first meets the therapist, she’s still looking for someone she can call “Papa.” The combination of no parental support (her father is dead and her mother entirely absent from the film) and loneliness has set up a prime candidate to latch onto the first person who shows her affection, regardless of how twisted.

Sumikawa is no less lonely, and the film depicts him with an eye which is so unjudgmental as to invite criticism. The speed with which Haruka’s changes from prisoner to partner, too, comes over less as credible, than smacking of sad wish-fulfillment for the (presumably middle-aged and male) audience. Haruka’s feeble efforts at attracting attention, before she gives up entirely, are so token they all but suggest this is secretly what she wanted, all along. She was asking for it, folks!

Yet, despite all these undeniable moral qualms, I still can’t entirely deny the merits of this, which takes its questionable topic seriously, and less exploitatively than expected. While 90% of it takes place in one apartment, it’s well assembled, and the performances are by no means inadequate. Hida, in particular, takes a character who could (and, arguably, should) be utterly unsympathetic, and gives him a poignant quality. If not the victim here, he’s still a victim. There are, apparently, seven films in the series, which seems a little much; from what I’ve read, they appear largely interchangeable variations on the same themes. I’ll likely review the first in a bit – covering only part 2 offends my sense of order! – yet get the feeling that’ll be quite enough.