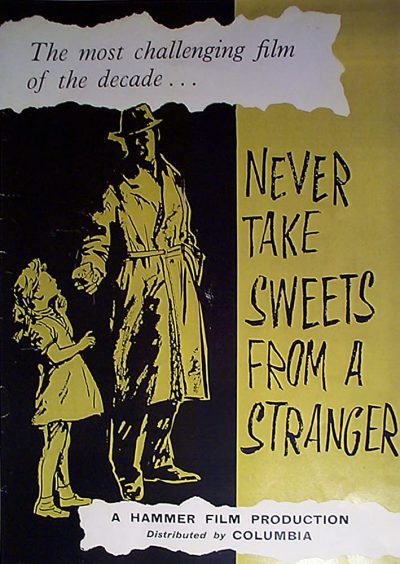

Rating: B

Dir: Cyril Frankel

Star: Patrick Allen, Gwen Watford, Felix Aylmer, Janina Faye

a.k.a. Never Take Candy from a Stranger

Most horror films decay over time. What was shocking at the point of release, gradually becomes normal as the years go by, and their impact is typically reduced as a result. But sometimes, society goes the other way. At the point of its release, this film, while not strictly “horror”, was a critical and commercial failure for Hammer. Michael Carreras subsequently said of their attempt to make a ‘message picture’, “Nobody bought it. I’m not an artist. I’m a businessman.” But over the sixty years since this came out, we’ve become far more sensitive to child sexual abuse. As a result, when 9-year-old Jean Carter (Faye) casually confesses, after her visit to the house of an old man, “We took all our clothes off,” the wallop this packs is startling.

The senior citizen in question, Clarence Sr. (Aylmer, who doesn’t say a word in the entire movie), is patriarch of the Olderberrys, a local family of renown, and the community closes ranks to protect them. It doesn’t help that Jean’s parents, Peter (Allen) and Sally (Watford), are new to the area, so are seen as troublesome outsiders. And it’s not as if Clarence hurt Jean physically or even touched her. Though he has a well-known reputation for “liking” children, and a previous stay in an institution, it proves remarkably difficult for the Carters to get traction for their complaint. Clarence’s son, Clarence Jr., takes particularly badly to the situation. He threatens both Peter’s position as school principal, and what will happen to Jean if the case goes to trial: “Don’t put that little girl of yours on the stand to testify against my father. Because if you do, don’t expect my lawyers to have any mercy on her.”

But still, they persist. And Clarence Jr. delivers on his threat, probably peaking in the defence counsel’s line to Jean: “So your daddy likes to see you dance naked?” It’s part of making his case that “The hideous and improbable charges brought against my client by this child are the result of a diseased imagination.” This proves an ugly, yet effective position for Clarence Sr. It succeeds in getting Peter to agree to drop the case, saving his daughter from an increasingly devastating ordeal. Facing an untenable situation, the Carters pack up and prepare to move on, only for Jean to have another encounter with Clarence Sr., who clearly has learned nothing from his recent acquital.

But still, they persist. And Clarence Jr. delivers on his threat, probably peaking in the defence counsel’s line to Jean: “So your daddy likes to see you dance naked?” It’s part of making his case that “The hideous and improbable charges brought against my client by this child are the result of a diseased imagination.” This proves an ugly, yet effective position for Clarence Sr. It succeeds in getting Peter to agree to drop the case, saving his daughter from an increasingly devastating ordeal. Facing an untenable situation, the Carters pack up and prepare to move on, only for Jean to have another encounter with Clarence Sr., who clearly has learned nothing from his recent acquital.

This scenario may have seemed a stretch for audiences at the start of the sixties. But the past decade showed exactly how people in positions of power could use that to commit truly heinous acts with impunity, and also suppress ruthlessly, any attempts to investigate or hold them accountable for their actions. Jimmy Savile, and his 450 victims, comes most readily to mind. That’s something of which I have experience, having been forced to take down a spoof Have I Got News For You transcript involving Savile, after legal threats to my hosting provider in 1999. The way in which the community refuses to act on the Carters’ accusations, feel eerily prescient of the way Savile was able to operate with impunity for decades, with the truth only coming out to the public at large after his death.

One weird thing is that it’s set in Canada. There’s no purpose to this at all: as the opening captions acknowledge, it could be anywhere, and it’s not as if the production was filmed there. The usual home counties locations were used by Hammer in addition to filming at Bray Studios; regular viewers may well recognize frequent location Oakley Court, here playing the part of a sanatorium. I’ve been unable to find if the setting reflects the source material, Roger Garis’s play The Pony Trap – an entity about which there is very little information overall online. Perhaps it’s an effort to sidestep the dangers of portraying a sensitive topic as happening in a major movie market? I’m basically clutching at straws for a justification.

Despite the geographical uncertainty, this could be the best Hammer film you’ve never heard of. I had certainly never seen it before; it wasn’t one I recall seeing on TV growing up, which is where I first watched most of the studio’s output. I think its failure probably consigned it to the cinematic memory-hole. Certainly, the UK poster (below) is woefully inaccurate and does the movie no justice. But its first 20 minutes are blistering, with an unsettling tone right from the start as Jean and her little gal-pal Lucille go to Clarence Sr’s house, after the latter has revealed, “I know somewhere where you can get some candy for nothing.” We never see what takes place that afternoon, which is why it comes as a shock – as much to the viewer as the parents – when the subsequent incident comes out. And that only happens because Jean stepped on a nail and is worried about getting tetanus. The actual naked dancing? No concern to her at all.

This lack of impact on the victim is why Sally’s mother, who was baby-sitting that evening, doubts whether action need be taken. [While Jean does have a nightmare, it could plausibly be a result of the bedtime story Granny tells her, “A little thing about a witch with three heads and one eye.”] The grandmother says, “I know how tough children can be. Happy, normal children, that is. And I know how much it takes really to shock them,” before telling how she had a not dissimilar experience when young. A mentally-challenged man in her village would, “I believe the term is expose himself” to the local girls, but “the sight of poor Percy didn’t do me any permanent harm.” It’s an unusual take, yet one not without its merits – at least initially. For subsequent events prove Clarence Sr. is unable to find any distinction between the harmless and the harmful in his interactions.

This lack of impact on the victim is why Sally’s mother, who was baby-sitting that evening, doubts whether action need be taken. [While Jean does have a nightmare, it could plausibly be a result of the bedtime story Granny tells her, “A little thing about a witch with three heads and one eye.”] The grandmother says, “I know how tough children can be. Happy, normal children, that is. And I know how much it takes really to shock them,” before telling how she had a not dissimilar experience when young. A mentally-challenged man in her village would, “I believe the term is expose himself” to the local girls, but “the sight of poor Percy didn’t do me any permanent harm.” It’s an unusual take, yet one not without its merits – at least initially. For subsequent events prove Clarence Sr. is unable to find any distinction between the harmless and the harmful in his interactions.

The performances here are all spot-on. I expected to not be able to hear Allen without being reminded of his work on Two Tribes for Frankie Goes To Hollywood, but that’s easily forgotten in his pursuit of justice, until it becomes apparent that it isn’t worth the price Jean has to pay. And in that role, Faye is excellent, running the whole range of emotions. Her scenes in the witness-box are tough to endure; credit Niall McGinnis and Hammer regular Michael Gwynn, acting for the defense and prosecution respectively, for their contributions. If the film has a flaw, it’s perhaps the final act. While tense, it feels almost as if it had strayed in from one of Hammer’s Frankenstein films, with the lumbering, silent monster pursuing its young victims through the woods. This is most effective when the threat is being understated, keeping it earthed in a reality which is all too plausible in 2020.

This review is part of Hammer Time, our series covering Hammer Films from 1955-1979.